Kalka.

Pavel RyzhenkoThe Mongol invasion appeared to be a real disaster for Rus’. The Russian princedoms, defeated by the nomads, became politically and economically dependent on the mighty Eastern empire for two and a half centuries.

The devastating invasion took place from 1237 to 1241, but the first time the enemies met on the battlefield was fourteen years earlier. How did this happen?

“Because of our sins, some unknown people came - godless Moabites, about whom no one knows exactly who they are and where they came from and what their language is and what tribe or faith they belong to,” was how a Russian chronicler described the appearance of the troops of Genghis Khan’s best commanders, Subutai and Jebe, on the Black Sea steppes back in 1222.

Having passed through Central Asia, they reached the Caspian Sea, crossed the Caucasus Mountains and invaded the lands of the Turkic nomads, the Cumans. The latter had once given hospitality to the Merkit tribe, defeated by the Mongols, and had to be harshly punished for it.

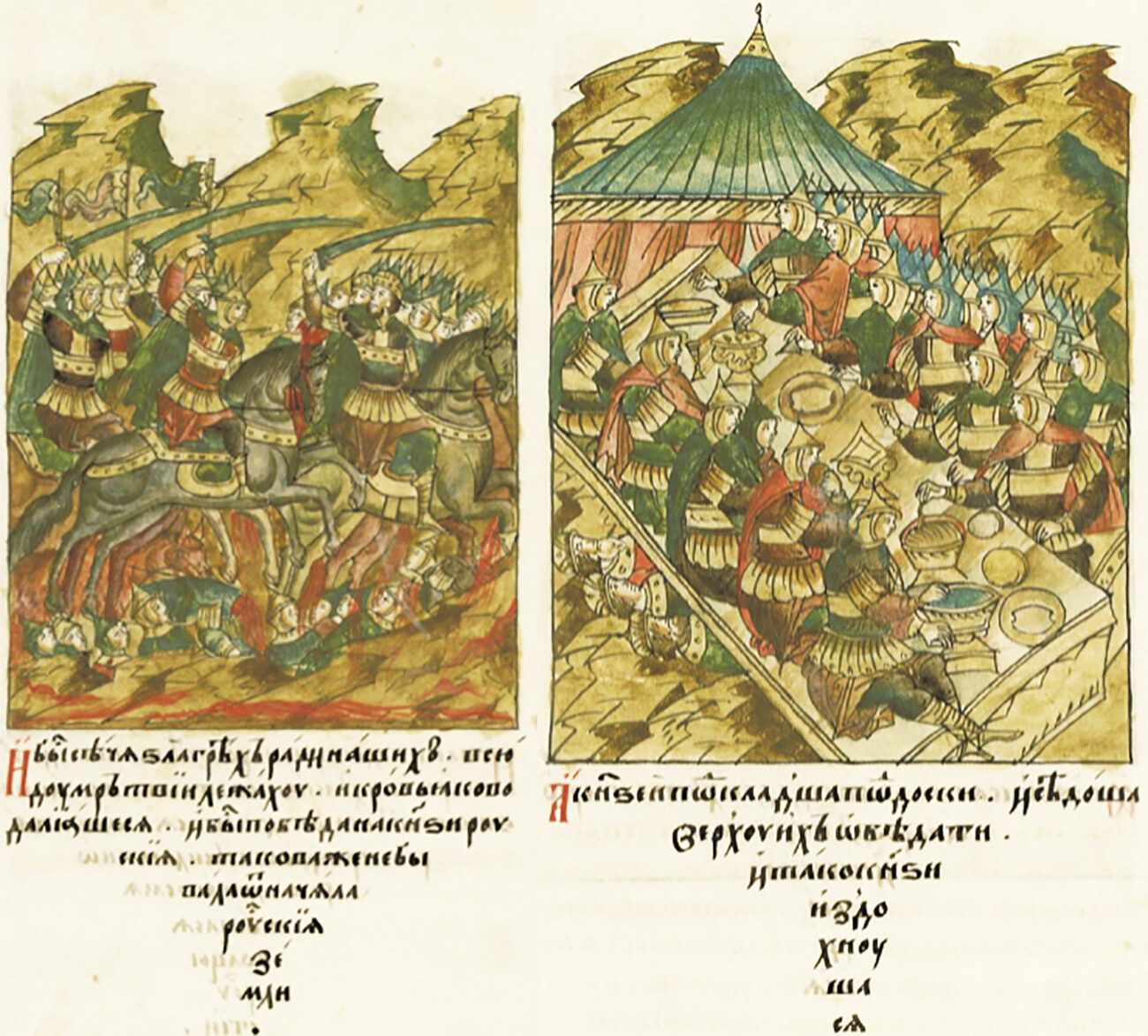

The 'Battle of the Kalka River'/Mongols feasting over the bodies of defeated Russian commanders.

Public DomainThe fragmented Cuman tribes could not give decent resistance to the best Eurasian warriors of the time and were forced to turn for help to their northern neighbors - the Russians, with whom they would fight furiously at times and would then make dynastic marriages and military-political alliances.

At the beginning of 1223, Khan Kotyan, the head of the Western tribal union of the Cumans, arrived at the court of Galitsk Prince Mstislav Udatny, who was his son-in-law. At the hastily organized gathering of the princes in Kiev, he began to persistently persuade them to stand up against the Mongols.

“And he brought multiple gifts - horses, camels and buffaloes, female slaves and, bowing, showered all the Russian princes in gifts, saying: ‘Today the Tatars have taken our land and tomorrow they will come and take yours and so help us,’” the chronicles read.

Fearing that the Cumans would join the Mongols in the event of their ultimate defeat, the rulers of several Russian lands agreed to fight the intruders.

The armies of the Kiev, Galitsko-Volynsk, Turov-Pinsk, Chernigov and Smolensk princedoms took part in the joint campaign, led by two dozen princes. In the early April of 1223, they moved down the Dnieper River into the southern steppes and, in the middle of May, they joined the Cumans near the island of Khortitsa.

The 'Battle of the Kalka River'.

Legion MediaThe number of allied forces was incalculable. According to different data, it ranged from 40 to 100 thousand people. Subutai and Jebe, in turn, had 20-30 thousand warriors, overall.

Faced with the numerically superior enemy, the Mongols tried to solve the matter peacefully. The ambassadors who came to the princes’ camp said that they were at war only with the Cumans, but not with the Russians. For unknown reasons, the ambassadors were killed, which, of course, was perceived by the nomads as a terrible insult. So, war became inevitable.

The Mongols, who, according to Arab historians of that time, had “the courage of a lion, patience of a dog, foresight of a crane, cunningness of a fox, farsightedness of a raven and the predatory nature of a wolf,” did not immediately engage in open battle with the enemy. They preferred to retreat from the Dnieper into the steppe, luring the Russians there, as well.

Opinions on how to continue the campaign were divided among the princes. Some supported Mstislav Udatny, who did not esteem the Mongols’ fighting potential and was willing to rush into battle. Others, led by Kiev Prince Mstislav Romanovich, called to act more cautiously.

When retreating, Subutai “fed” small military units to the enemy, allowing them to score inspiring victories. Eventually, the Russian-Cuman army became fully engaged in the pursuit.

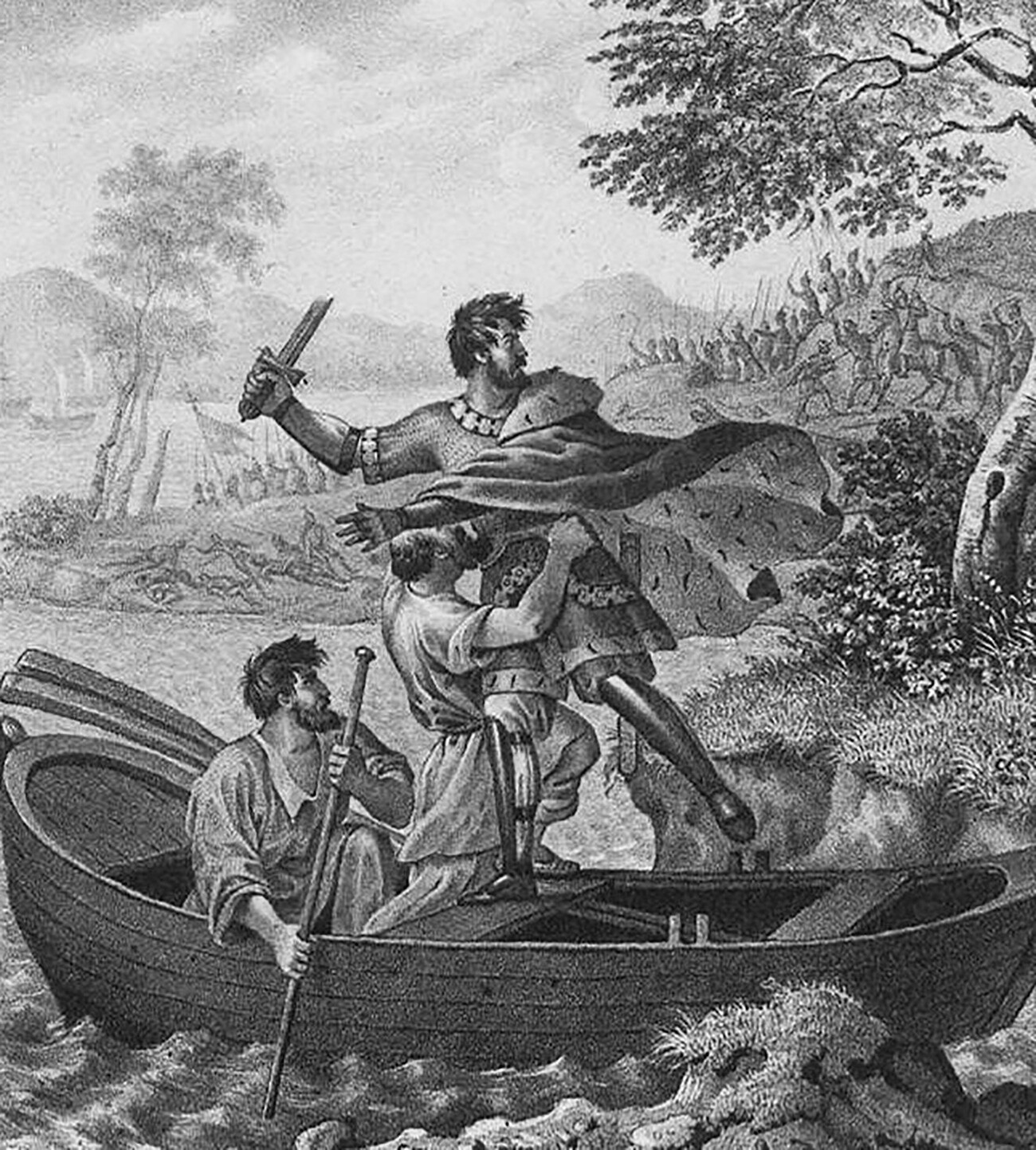

Prince Mstislav Udatny flees after the defeat.

Boris Chorikov (CC BY-SA 4.0)After a week of marching, the allies came to the small river Kalka (today - presumably in Donetsk Region), where, on May 31,(according to other data - June 16 or July 16) a climactic battle took place.

One part of the pursuers crossed to the other river bank and rushed after the Mongols, while the other part had not even begun the crossing. Having waited until the distance between the units of the enemy’s army was a few dozen kilometers, Subutai attacked.

Imitating a retreat, the heavy cavalry of the Mongols turned around abruptly and hit the stunned Cumans. They were instantly crushed and then fled, wreaking havoc on the units of the approaching Russian forces. “And the Russian regiments were in confusion and the battle was disastrous, due to our sins. And the Russian princes were thrashed and there had never been such a terror since the beginning of the Russian land,” the chronicle says.

The Kiev prince, who was on the other side of the river, chose not to engage in the fight. He entrenched himself in the camp, which was soon besieged by the Mongol troops. At the time, other groups of nomads continued to pursue the remaining troops scattered across the steppe, inflicting severe damage on them.

A few days later, the Mongols suggested that the besieged, who had already begun to suffer from thirst, surrender, promising to release them for a ransom. Instead, the surrendered Kievan warriors were in part slaughtered, while the others were captured. Mstislav Romanovich and several other princes and commanders were put under planks, on which the victors arranged a feast and died of suffocation under the crushing weight.

Mongols celebrating victory in the Battle of the Kalka River.

Legion MediaThe first armed clash of the Mongols with the Russians ended in a terrible disaster for the latter. A vast number of noble boyars perished and of the several dozen princes who took part in it, as many as twelve did not return home.

It is impossible to calculate the exact losses of the Russian army, but it is known for sure that they were enormous. According to the chronicles, only every tenth warrior survived.

“And there was weeping and wailing in all the towns and villages,” reads the Tale of the Battle of the Kalka, from the 13th century. The widespread disdain for the nomads among Russian princes was replaced by a panicked fear of them.

The lack of a unified command and coordination in the actions of the units, as well as the princes’ inability to reach agreement in the face of a common threat were the main causes of the overwhelming defeat. Yet, no conclusions were made from those unfortunate events and the old unresolved issues became relevant again fourteen years later, when a full-scale Mongol invasion was started directly against the Russian lands.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox