From ancient times onward, people tried to learn the ways of nature and the movement of celestial bodies. Back in ancient Babylon, people came up with the idea to split the celestial circle into 12 parts, each represented by its own astrological sign. Over the course of a year, the Sun passes each of them in order and every single one of these periods was attributed with a symbolic meaning.

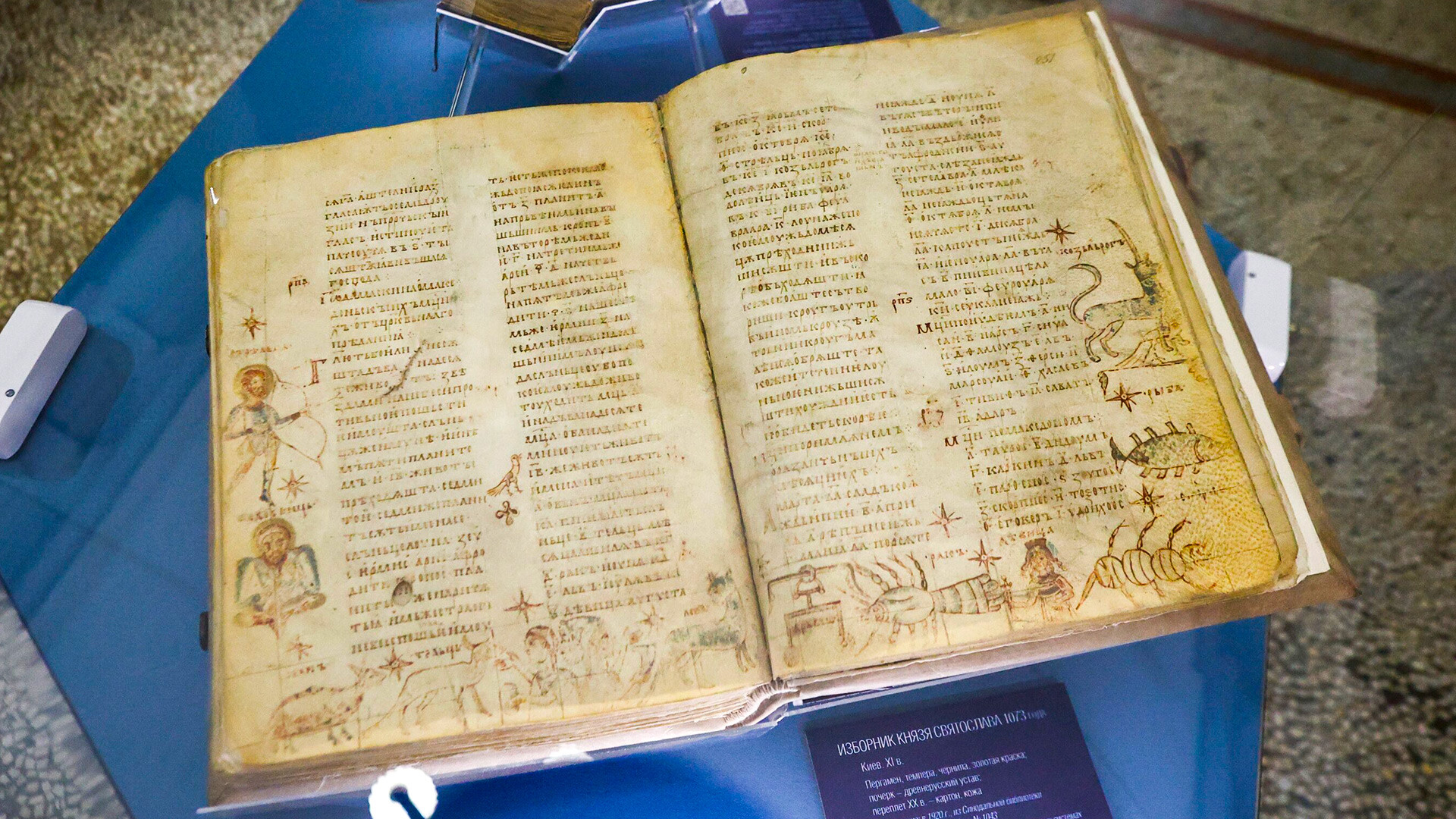

Ancient Russia learned about astrology through Byzantium, the envoys of which first spoke of some “good” and “evil” days – mostly concerning household activities and everyday life. The ‘Izbornik of Svyatoslav of 1073’ is the first document in Russia that survives to our day and contains information about astrological signs and their depictions. Essentially, it’s an 11th-century encyclopedia that speaks of Christianity, morality, mathematics and natural science. In particular, a translation of the text by John of Damascus about calendar systems is published in the Izbornik – and, for illustration, astrological signs are depicted on the margins.

‘Izbornik of Svyatoslav of 1073’

Yaroslav Chingayev/Moskva AgencyThe Christian Church officially opposed astrology. The principle of fate divination was against the teachings of the Bible – for only God knew it. The Christian Church also didn’t favor other superstitions and character descriptions.

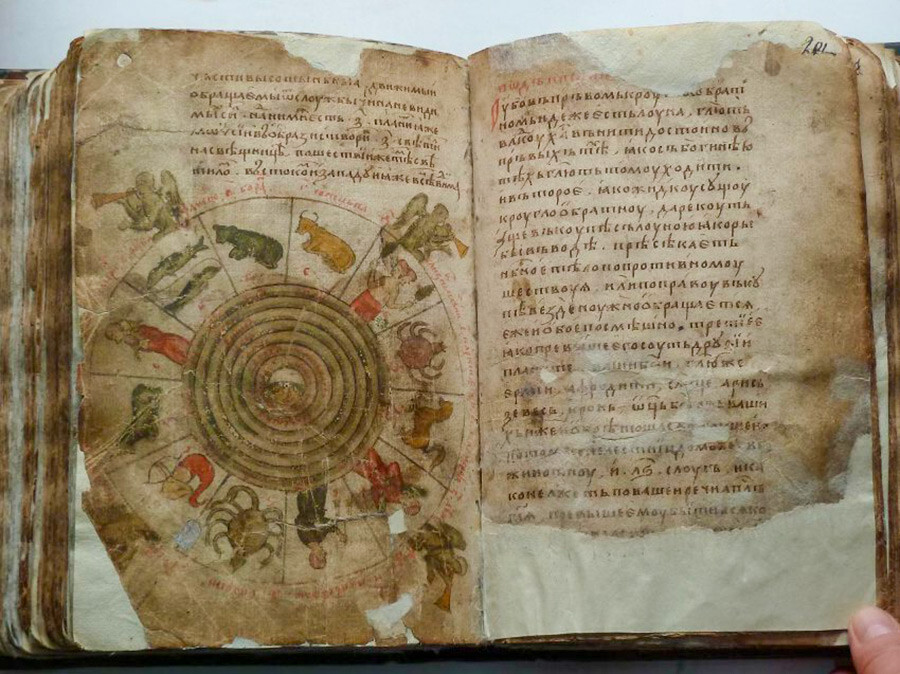

However, as Russia got closer to Europe, where astrology and astrological signs were already popular, the teachings about them penetrated ever deeper. It was especially prominently reflected in books. For example, in 1494, the Russian version of the famous Greek ‘Christian Topography’ by Cosmas Indicopleustes was printed. This book is one of the first Christian descriptions of the world. It also included an explanation of the understanding of the organization of celestial bodies and the zodiac wheel.

The Russian version of ‘Christian Topography’, 1494

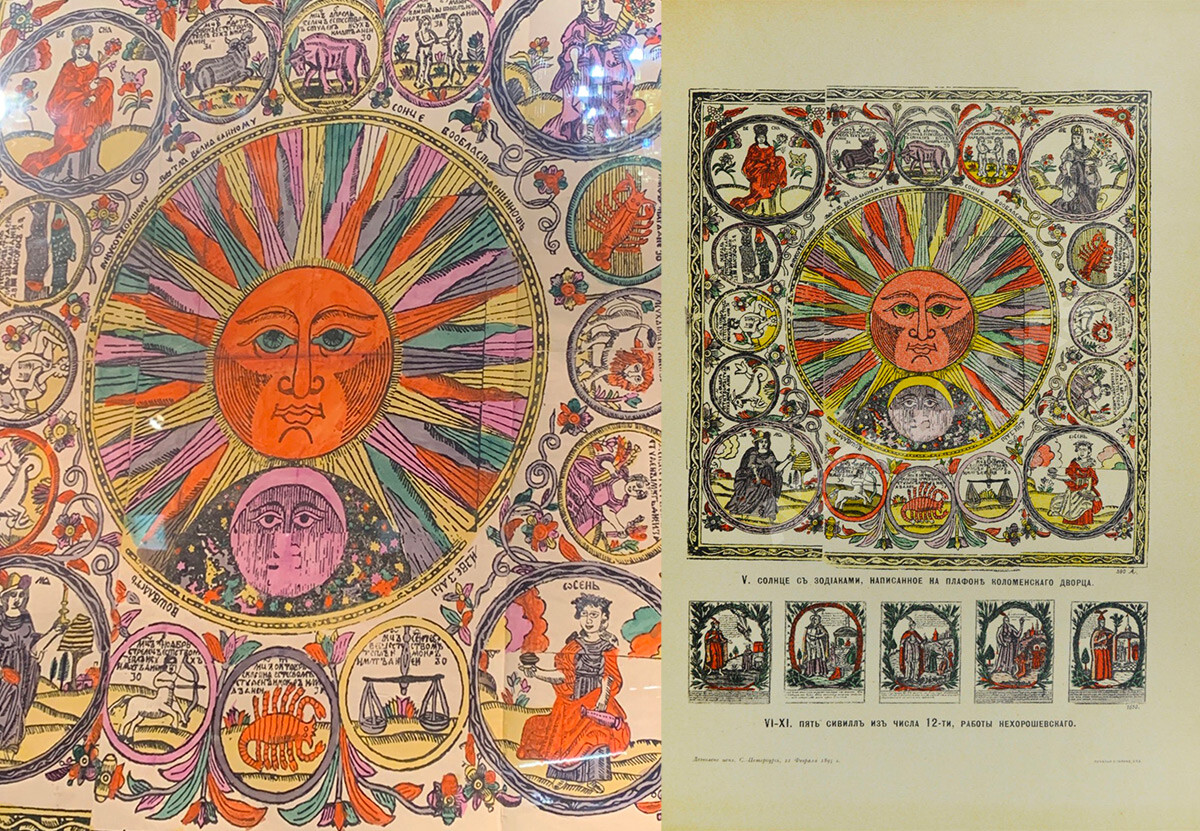

State Historical MuseumIn the second half of the 17th century, under European influence, court culture began to form. And astrology and horoscopes with fortune-telling penetrated even deeper into all levels of Russian life; even Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was interested in them. The Sun and astrological signs decorated the plafond of his Kolomensky Palace in Moscow, built in the 17th century. The palace itself didn’t survive, but the picture of the plafond was printed in 1881 in the ‘Russian Folk Images’ atlas, published by Dmitry Rovinsky.

The Sun and astrological signs in the ‘Russian Folk Images’ atlas

State Historical MuseumThe description of the plafond also survived and, in 2011, a replica of the painting appeared in the restored Kolomensky Palace.

Palace of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich

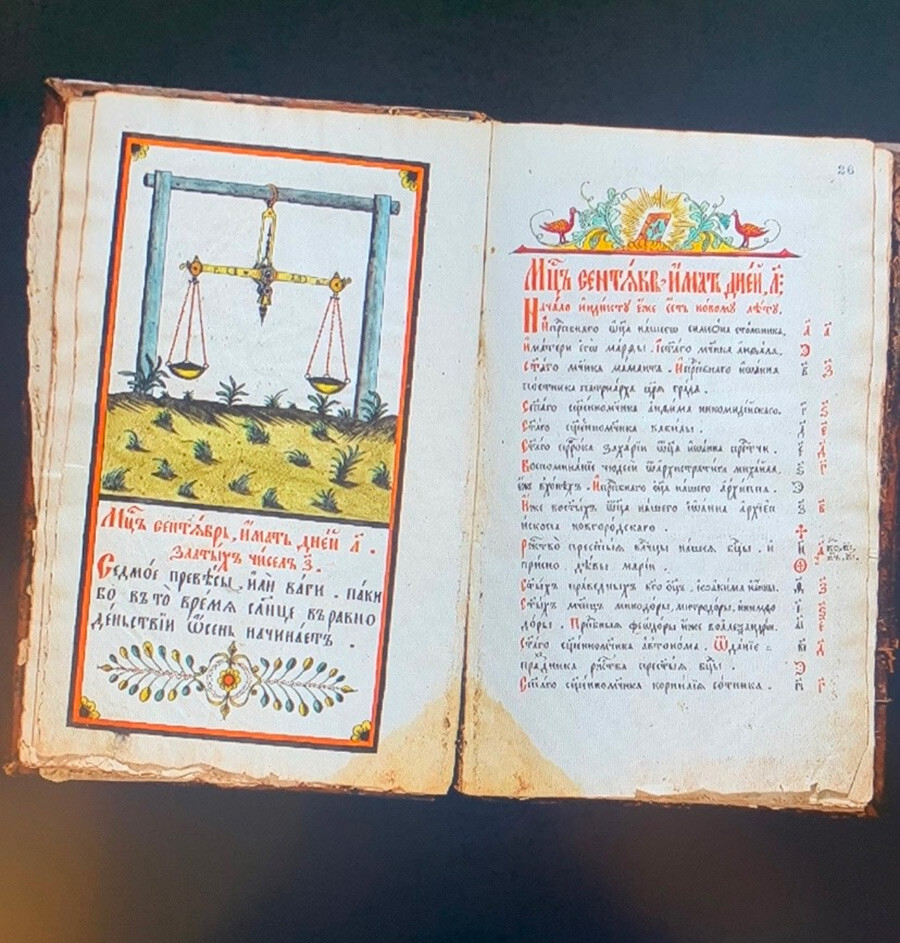

Kolomensky museumAlthough astrology and astrological signs opposed the position of the Orthodox Church, they slowly infiltrated even the ‘Mesyatseslov’ (‘Menologium’), a sort of a calendar, where religious and folk holidays were noted, as well as traditions and omens connected to nature and everyday life. Below, for example, is a page from ‘Mesyatseslov’ of the 17th century about the astrological ‘Libra’ sign.

The 17th century ‘Mesyatseslov’ (‘Menologium’)

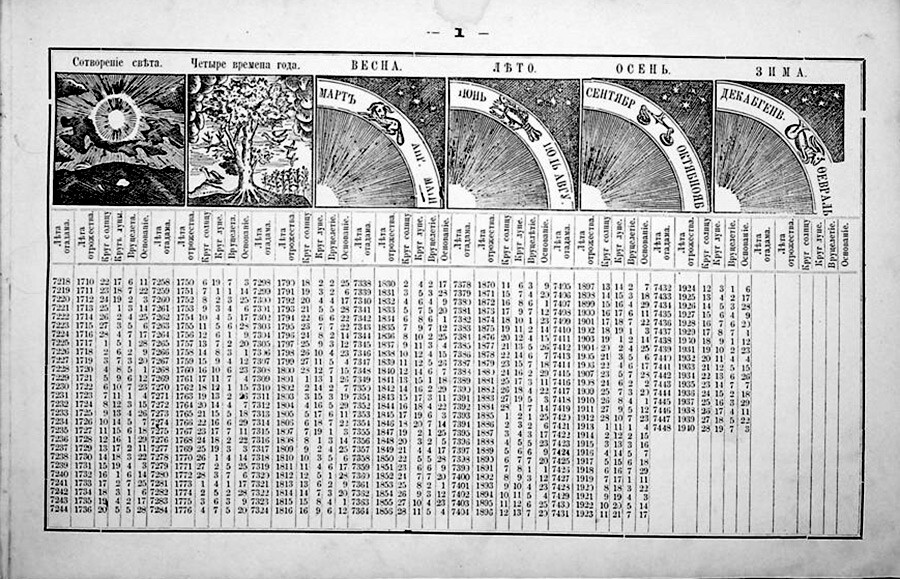

State Historical MuseumUnder Peter the Great, interest in astrology only strengthened further. His associate Count Jacob Bruce composed his famous ‘Bruce Calendar’, designed for 200 years ahead. It had information about church and secular holidays, as well as a lot of other information, including astrological and agricultural facts. Village priests, small-time landowners, craftsmen, as well as merchants read this calendar – and, from it, they drew advice on when it was best to get a haircut or engage in trade, according to the phases of the Moon. The calendar also had fortune-telling and character descriptions for astrological signs.

A page from the ‘Bruce Calendar’

State Historical MuseumBooks under the names ‘Planetnik’ and ‘Zodiachnik’ were published “for curiosity and public amusement” in the 18th century. They had no illustrations, but they had detailed descriptions of the characters of people who were born under the auspices of a certain planet, as well as of the characteristics of astrological signs – even in looks. Here’s, for example, what is written about Sagittarius: “Those born under this sign will be eloquent, will have a wide face and dark eyes, broad shoulders, straight hair on their head, a birthmark on their chest or forehead; they are righteous and are of a cheerful disposition.” It says that people born under the ‘Aries’ sign are “good-natured and friendly” in their character, while people born under the ‘Leo’ sign are “brave and indomitable”, but those born under the ‘Capricorn’ sign, for example, “promise a lot, but give little”. Overall, it’s similar to the modern description of the signs.

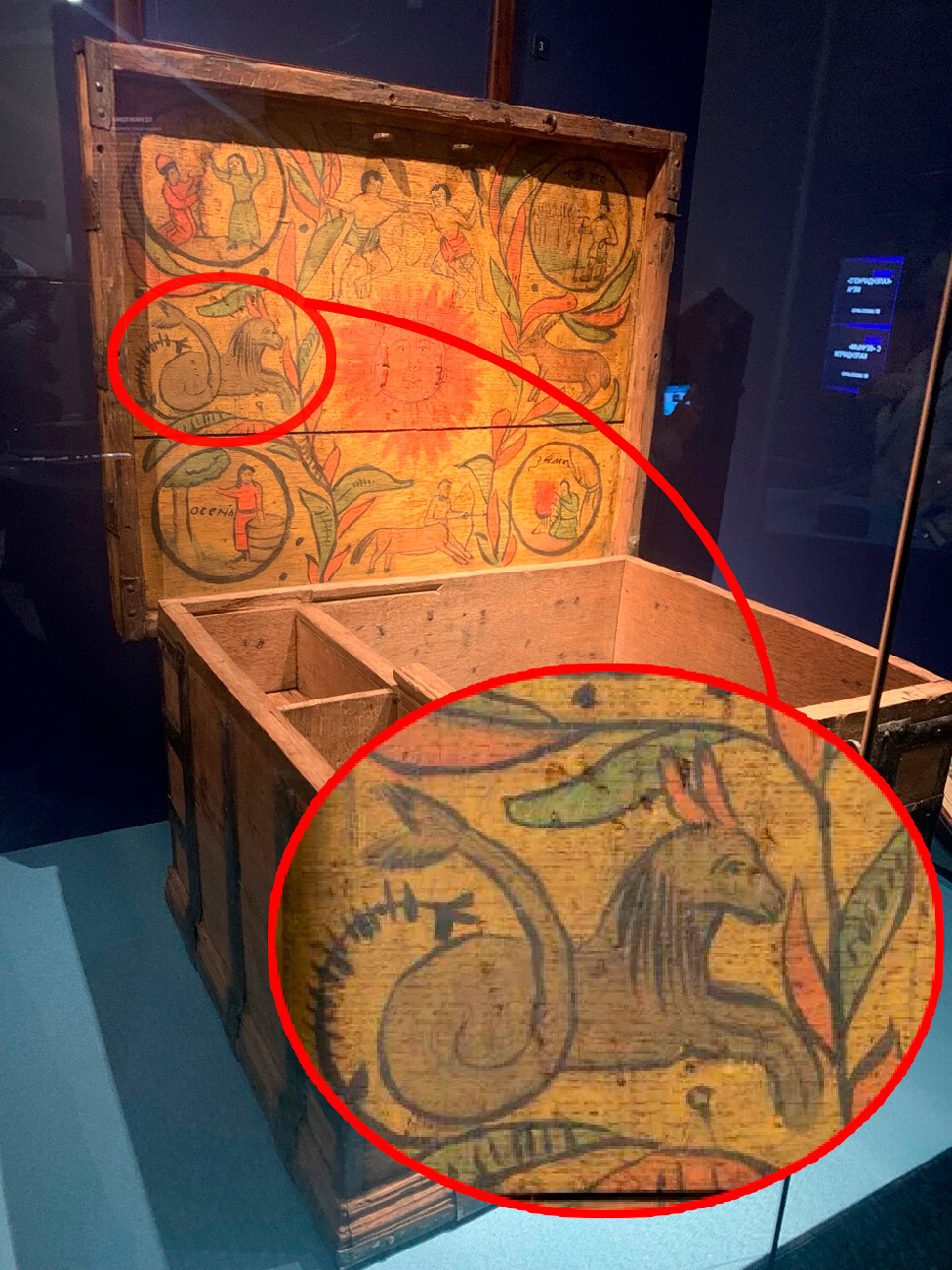

Astrological symbols penetrated even folk handicrafts. Take a look at the inside of the lid of the ‘Seasons’ chest, created in the Russian North at the end of the 18th – beginning of the 19th century. Apart from lubok depictions of the seasons, it also features the pictures of astrological signs, symbolizing the elements. ‘Sagittarius’ on the bottom signifies fire, ‘Capricorn’ on the right means earth, ‘Gemini’ on the top signifies air, while ‘Scorpio’ on the left means water (obviously, the Russian painter, who had never seen this exotic animal, depicted it as a mysterious creature with a forked tail!).

‘Seasons’ chest

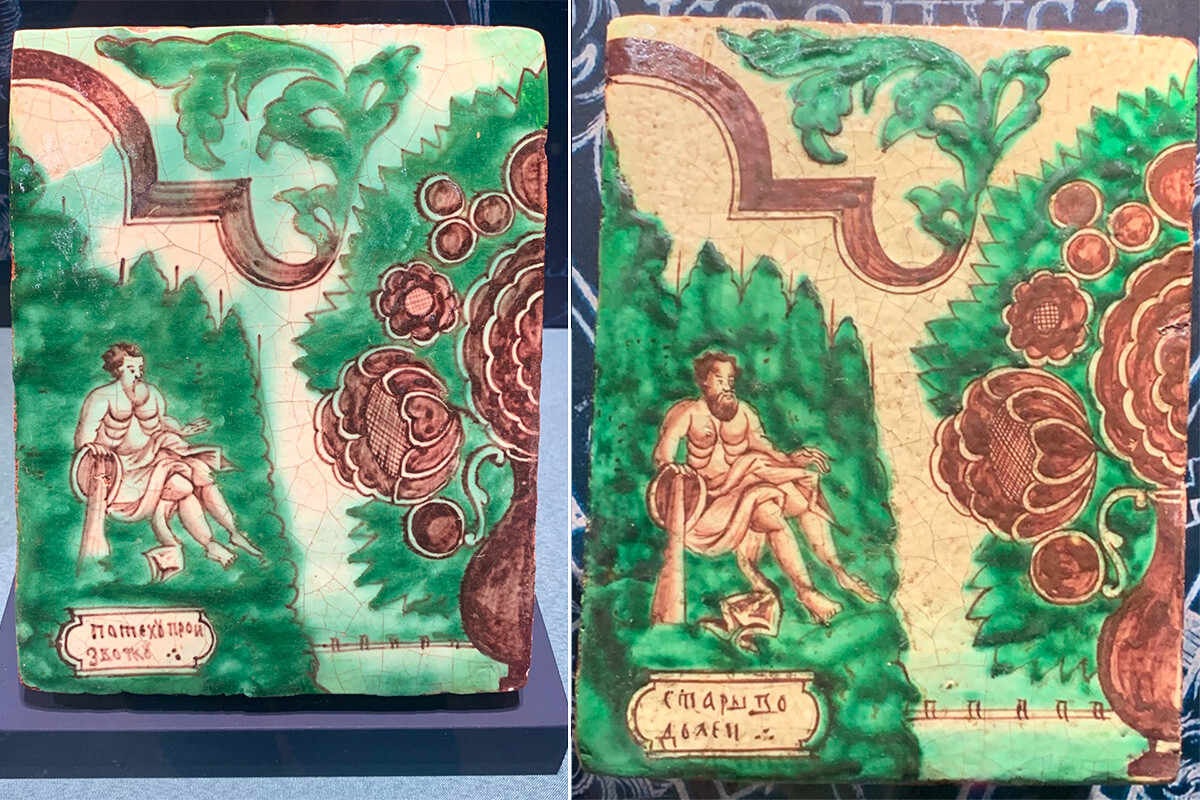

Alexandra GuzevaAstrological signs actively infiltrated the interiors of different social classes: paperweights in the shape of crayfishes were produced and vases with fishes; statuettes with lions were being produced in Gzhel back in the 18th century. The symbols appeared also on decorated oven tiles. For example, below are two 18th-century Moscow clay tiles depicting ‘Aquarius’. One of them has “Potekhu proizvozhu” (“Making fun”) written on it.

Oven tiles with ‘Aquarius’

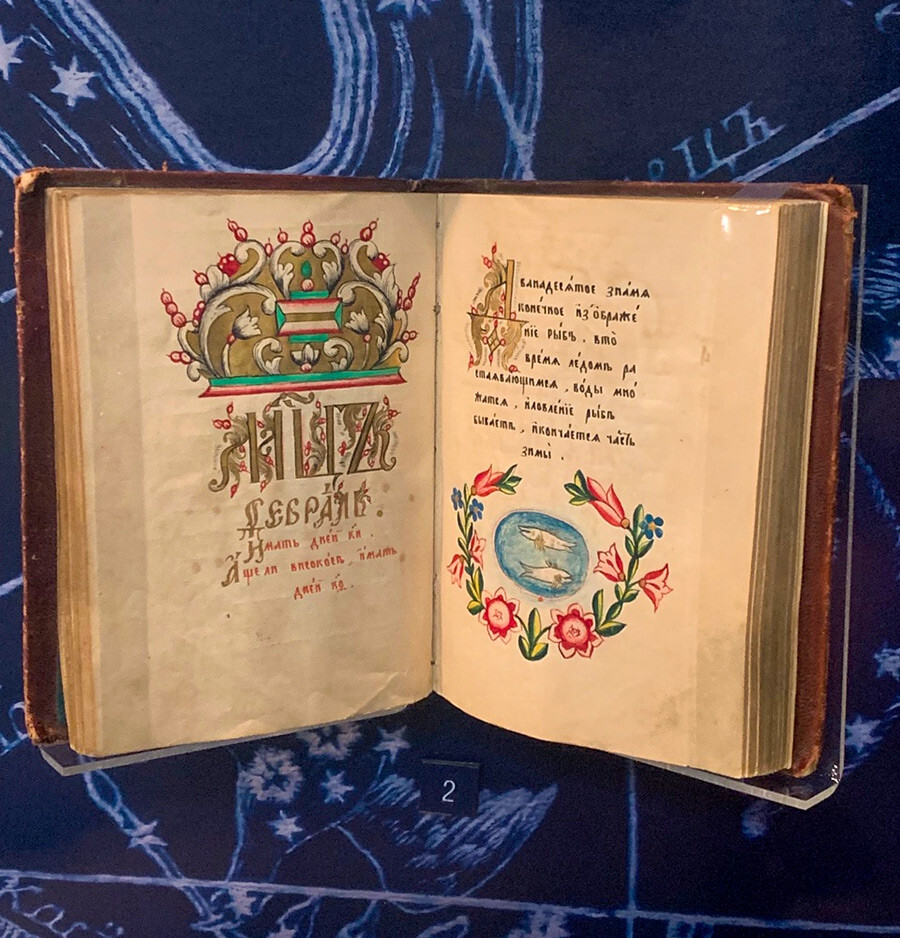

Alexandra GuzevaThe depictions of astrological signs were especially popular among the Old Believers, who didn’t follow any directions from the official Orthodox Church. They published illustrated calendars-menologiums with ‘Paskhalia’, a system of a calendar and astronomical calculation of religious holidays. Below, you can see a page from an Old Believer menologium from 1836 with the ‘Pisces’ sign that signifies the end of winter.

1836 calendar

State Historical MuseumIn 1884, book publisher Ivan Sytin began publishing calendars for the public. They were released in massive editions and, according to the publisher, “the calendar gave the people instructions for every occasion”. They were also brightly decorated; in different years, the cover featured the imperial family, scenes from Russian life or historical paintings. In 1915, the cover of the calendar was decorated by an image of an astronomer with a telescope and astrological signs.

1915 calendary

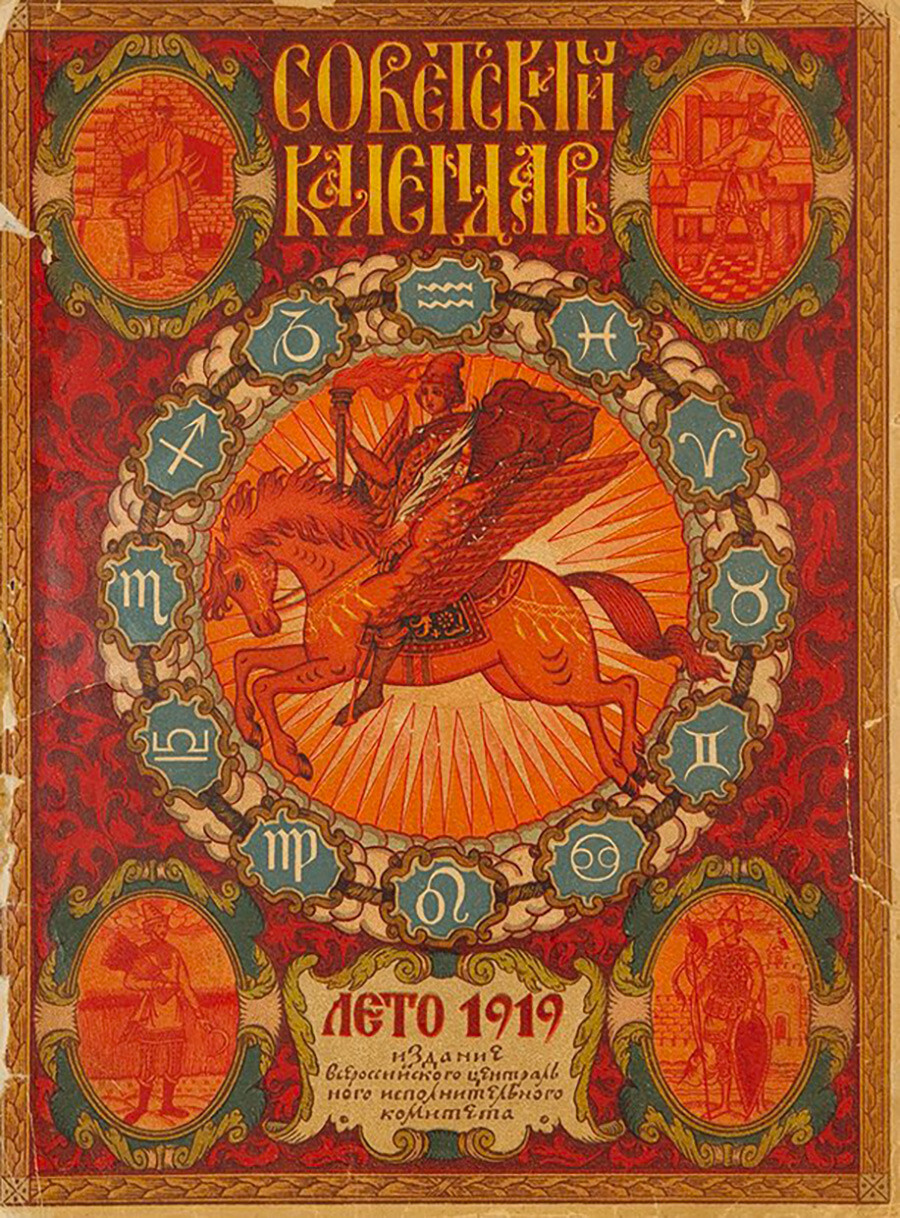

Ivan Sytin publishing houseSoviet authorities also didn’t oppose astrology. The zodiac wheel, for example, is depicted on a 1919 calendar.

1919 calendar

All-Russian Central Executive Committee's publishing houseIt also appeared on the 2024 ‘Universal desktop calendar’, printed by the state publishing house.

2024 calendar

GIZ (State Publishing House)The ‘Under the astrological sign. Monuments of culture from the ancient times to our day from the collection of the Historical Museum’ exhibition will be displayed in the Chairman’s Office at the State Historical Museum from December 13, 2023, until March 11, 2024.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox