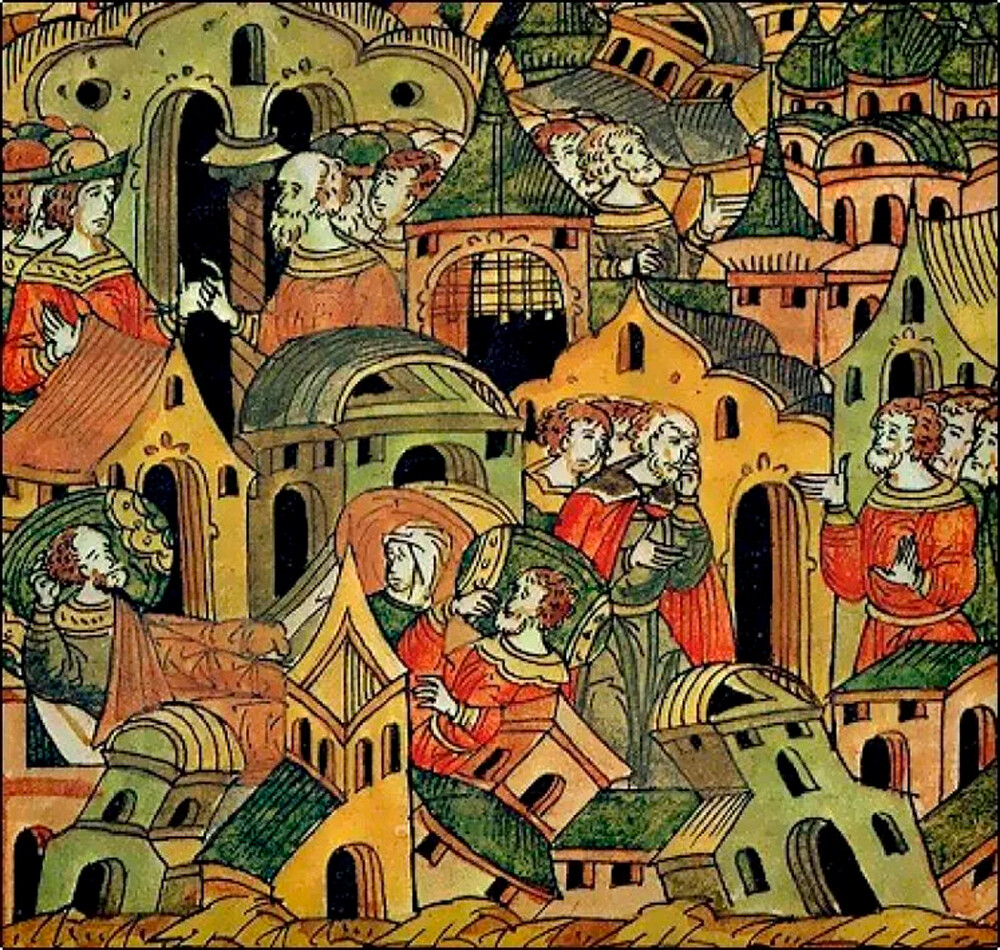

It may be hard to believe, but the city has been hit by earthquakes several times. 15th-century chronicles mention how the ground suddenly trembled and bells started ringing by themselves. There was an earthquake in 1474 that, according to researchers, was at least a 6.0 magnitude: The ‘Great Quaking’, as contemporaries branded it, destroyed the Dormition Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. The cathedral, which the Pskov masters Krivtsov and Myshkin had completed up to roof level, collapsed as if crushed by an invisible giant hand. In any case, the disaster had a plus side, too: It was after the earthquake that Ivan III invited Aristotele Fioravanti from Italy to rebuild the cathedral.

Moscow also shook in October 1802. And, again, the kremlin was hit: Builders working on the Spasskaya Tower claimed that it shook noticeably. In some houses, the chandeliers swayed, furniture rattled and walls cracked and, in places, the ground caved in. But, the few tremors that occurred were not enough to give a real fright to the city's residents, whose life quickly returned to normal.

The capital itself is situated in a seismically stable zone, so almost all earthquakes in the city would have been reverberations of more significant natural disasters elsewhere. For example, in December 1945, the reverberations of an earthquake off the coast of Antarctica reached Moscow. The terrible Bucharest earthquake of March 4, 1977, was felt throughout almost the whole of Eastern Europe: In residential buildings, the furniture shook violently and ceiling lights swayed, and in high-rise structures like Moscow State University, the oscillations reached magnitude seven.

In 2013, the Russian capital could feel the reverberation of an earthquake centered in the Sea of Okhotsk that shook all European countries. In Moscow, residents were even evacuated from several high-rise buildings.

What happens if you combine a fire that devours everything in its path with warm weather and wind? You get a firestorm. It was what Napoleon observed in 1812 as he was leaving Moscow. It is not by chance that the phenomenon is called a demonic fire: Fires broke out in different parts of the city, stores selling combustible materials exploded and the wind spread the fire further and further. The fires eagerly devoured wooden buildings: There was no point in extinguishing anything and there were no appliances that could be deployed, as, on leaving Moscow, the firefighters had taken all their equipment with them.

The intensifying wind only accelerated the conflagration. In the dead of night, the fiery streams combined and formed a firestorm that destroyed the city as it went. Napoleon managed to get out of the kremlin, although it was not easy: The roadway was melting from the heat. He returned four days later, but charred ruins were all he found. Napoleon described the fire as the greatest, the most majestic and the most terrifying spectacle he had ever seen. The fire lingered in the city for a long time: When more than a month after the disaster Russian troops entered Moscow, the city was still smoldering.

Photographs from 1904 captioned: "Tornado observed from Pererva station 13 verts [about 12 km] from Moscow" show a wall of black cloud covering the whole sky. The storm front extended over a width of 15-20 km. The city was hit by violent winds reaching speeds of 25 meters per second coming from the direction of the Tula Governorate in the south. It raged over the eastern suburbs and divided into two tornado funnels, which brought destruction to Karacharovo, Lyublino, Chagino, Kapotnya, Grayvoronovo, Annegofskaya Roshcha, Kalitniki and Kuzminki (all now administrative districts of the city) and then plowed through Lefortovo, Losiny Ostrov, Sokolniki and Basmannaya Chast. The turbulent currents of air uprooted trees, tore crosses off churches and swept up pitifully screeching cows and goats.

"Suddenly, everything started to swirl… in the midst of zigzagging shafts of lightning, there were flashes of yellow light and a fiery crimson-yellow column spun in the middle. Within a minute, this deafening horror had raced past, destroying everything in its path," wrote local historian Vladimir Gilyarovsky.

In July and August 2010, a thick yellow-brown haze descended on Moscow: smoke from burning peatland in Moscow Region covered the city in a dense shroud of smoke. A suffocating heat (thermometers regularly indicated temperatures of up to 37°C) and the constant smell of burning enveloped the city. The haze even penetrated the city’s subway system: carriages and stations were plunged into semi-darkness and passengers were forced to cover their faces with damp cloths or to wear respiratory masks. River transport services were suspended, some offices closed and, in stores selling domestic appliances, the most sought-after goods were ventilators and air conditioners. These immediately began to sell out and it became quite a challenge to get one's hands on either. Over several weeks of dense smog, the mortality rate in Moscow doubled. The smoke from burning peatland only disappeared from the city on 18-19 August and the heat was finally replaced by cooler temperatures and rain.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox