Stalin was not very fond of flying and got into an airplane only in exceptional cases. At home and abroad, he preferred to travel by train.

Thus, it was by train that the Soviet leader regularly went on vacation to Crimea and the Caucasus. He would climb aboard early in the morning and, by the evening, he would already be at his destination. His habit of traveling on the railroads in the daylight hours had been preserved since the Civil War - locomotive crew and guards could see everything that was going on around the train.

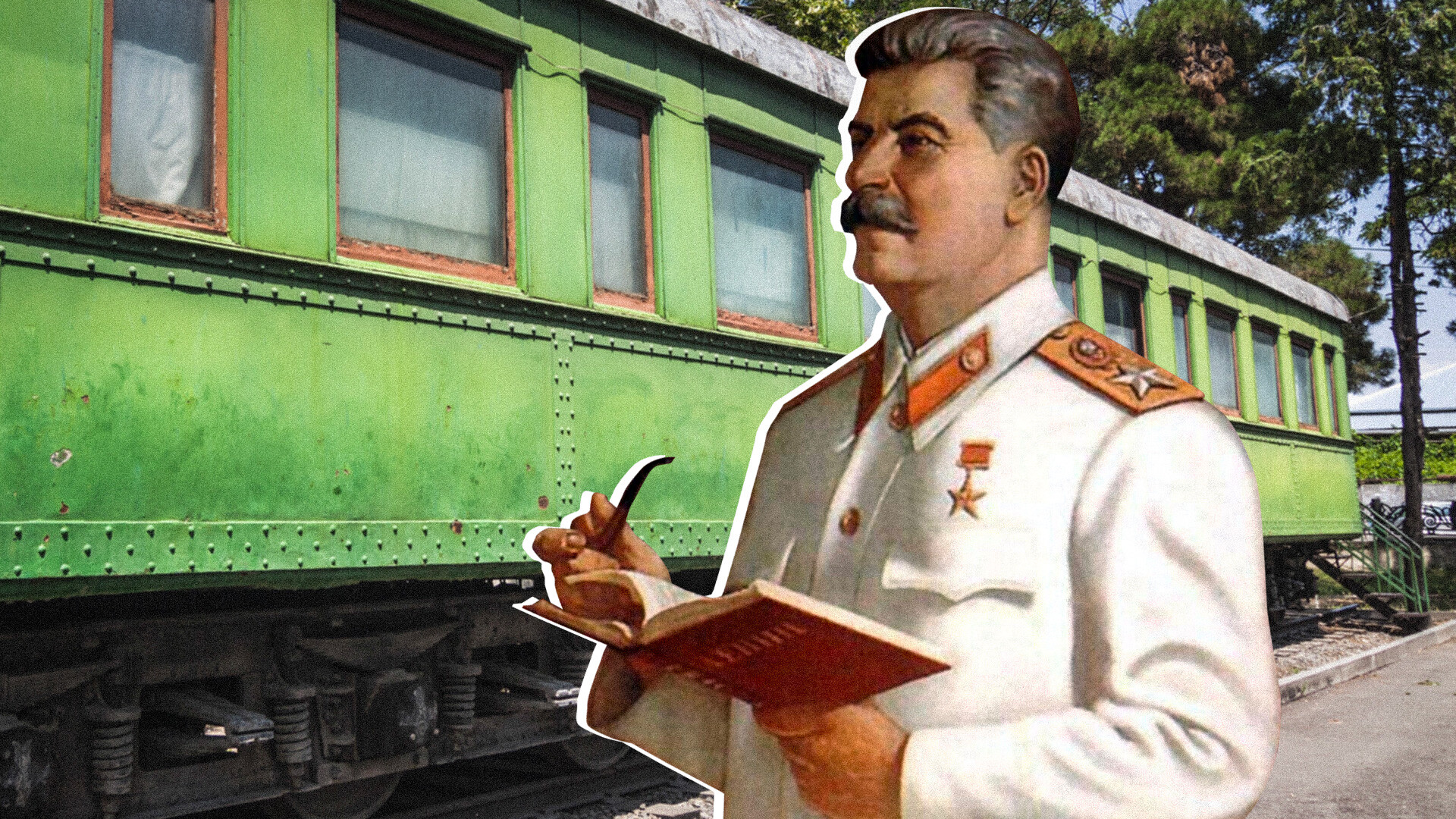

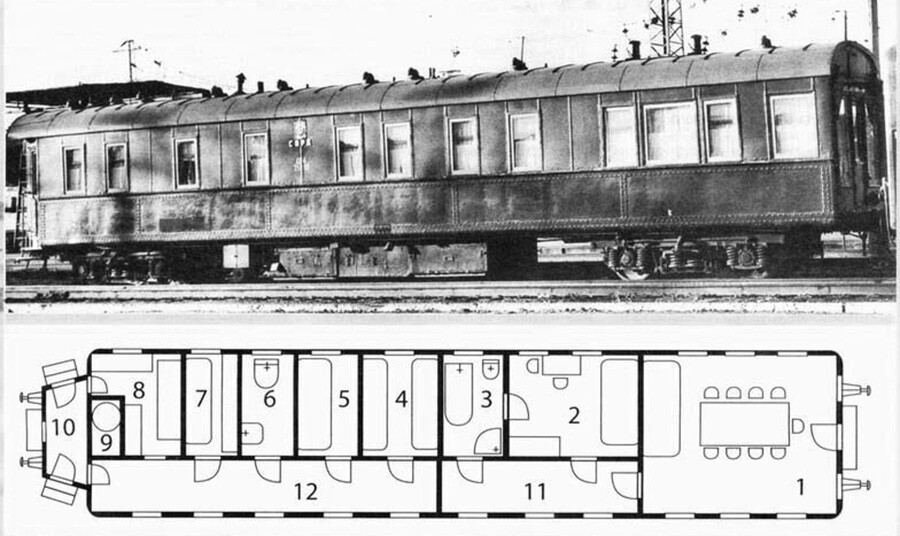

The leader's train consisted of three or four railroad cars. The car in which Stalin himself rode was no different to regular railroad cars, except that it had armored walls and floors. Due to this, it was heavier – 80 tons instead of 60.

In this car, the ‘Father of Nations’ had a private compartment and a personal toilet at his disposal. Next to it was a kitchen, compartments for VIPs and security guards accompanying him and a mini conference room for meetings.

Despite the high position that Stalin occupied, the interior of his car is difficult to call luxurious. Compared to the railway car of the Romanov family, it was extremely humble and moderate in design.

Other cars accommodated railroad workers, guards and various levels of military leaders and officials. There was also a restaurant with a larder. During World War II, two platforms with anti-aircraft guns were attached to the train to protect the leader from possible attack from the air.

In 1943, Stalin traveled by train to the Tehran Conference (he reached Baku, from where he flew to Iran by plane). In 1945, he traveled by rail to the conferences in Yalta and Potsdam. The trip to post-war Germany was prepared especially carefully.

"Seventeen thousand soldiers and officers of the NKVD and 1,515 operational staff ensure the safety of the way,” said the then Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR Lavrentiy Beria in a report. “On each kilometer of railway track, from six to 15 people will be guarding. There will be eight armored trains of the NKVD along the line."

The train was pulled by a powerful American ‘ALKO’ diesel locomotive, which the U.S. had supplied to the USSR under the lend-lease program. All the way to its destination, it followed the wide (1,520 mm) "Russian" tracks, which the troops of the 1st and 2nd Byelorussian Fronts had changed from the European track (1,435 mm) during their offensive..

Naturally, the journey wasn’t without incidents. When approaching the Oder River, the train had to brake for a long time, as a result of which the brake pads began to smoke. Assistant machinist Vasily Ivanov looked out to find out what was wrong, got caught on the semaphore signal and fell to the ground. The train stopped, the victim was helped up and sent to the hospital at the nearest station.

"The day of departure from Potsdam came,” recalled machinist Victor Lyon. “Stalin arrived at the station and went straight to our diesel locomotive. His first question was addressed to me: how does Vasily Ivanovich feel? Instead of me, Ivanov, who looked out of the locomotive at that moment, answered himself: "Good, Joseph Vissarionovich. Stalin looked at him, wagged his finger and said: ‘Be careful!’"

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox