Work and Travel: U.S. closes door on Russia’s students?

It remains to be seen how many students will go to the U.S. as participants of the Work and Travel program in 2013. Pictured: U.S. Embassy in Moscow. Source: ITAR-TASS

The recent cases of Russian Work and Travel visa applicants being denied American visas indicates that the visa issue hasn't being resolved yet. While some observers claim that the stance taken by the U.S. Embassy might be politically motivated, Russian experts see these restrictions as a reasonable response to the lack of control on Work and Travel participants. Likewise, U.S. officials view the move as an attempt to introduce higher requirements for students.

Work and Travel

Summer Work and Travel was created as a public diplomacy tool in 1963. It allows foreign university students to work and travel for up to four months in the United States, where most work entry-level jobs at resorts, theme parks and restaurants, and experience American culture. The only firm requirements for participation in the program are a working knowledge of English and to be a full-time student at a university. About 1 million students have participated in the program. Participants come from around the world; some of the top participating countries are Russia, Brazil, Ukraine, Thailand, Ireland, Bulgaria, Peru, Moldova and Poland.

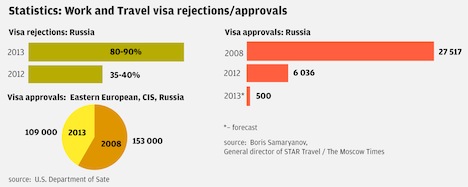

In early April, Moscow’s English-language newspaper The Moscow Times reported that 80-90 percent of the Russian students who have applied for visas to participate in the U.S. government’s Summer Work and Travel program since mid-March have been rejected. The information came from several U.S.-Embassy approved Russian agencies that manage Summer Work and Travel applications.

The paper went on to report that at the same time, last year the U.S. embassy rejected only 35-40 percent of the Summer Work and Travel visa applications.

Some observers claim that the rejections are a reflection of the difficult political relations between the U.S. and Russia, while others think the rejections are a justified response to the lack of control of the Summer Work and Travel participants and employers. Meanwhile, some U.S. officials regard the rejections as an attempt to introduce more stringent requirements for students who apply for visas.

Tara Sonenshine, U.S. Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs, addressed the issue during a question-and-answer session at the American Center in Moscow on April 10.

“Over time, the number of summer work travel programs in the U.S. has gone up, up, up. And quality sometimes suffers when you grow extremely big with a number of programs,” Sonenshine said.

Statistics: U.S. Embassy rejects Work and Travel visa applicants. Click to view the infographic.

She went on to explain that the U.S. has to make sure that everyone who is accepted into the program has a good experience, which means that they have had to take a more serious look at the students and the U.S. firms who hire them.

"Our most important priority is the security, health and well-being of people who come for a summer to travel and work," she said. “We have to put on some more difficult restrictions because we were finding in some cases that we are not able to deliver a highest possible quality. Any time when an international visitor comes to the United States, it has to be a positive experience. If it is negative in any way, it is going to be hard for everyone.”

In 2011, Summer Work and Travel participants staged a walk-out at a Hershey chocolate factory in Pennsylvania saying that they were being used as underpaid labor.

Russian experts agreed with Sonenshine’s assessment that the recent cases of visa rejection are a result of more stringent requirements for participants rather than politics.

“There is no politics [behind the U.S. Embassy move] at all. I don’t see it as a U.S. asymmetrical response to Russia’s NGO law. It’s too shallow for politics,” said Maxim Bratersky, a research fellow at the Center of Comprehensive European and International Studies (CCEIS) at the Higher School of Economics (HSE). “Americans have been always open for foreign students and exchange.”

Related:

Educational programs remain central in U.S.-Russia collaboration

Andrey Kortunov, president of the Moscow-based New Eurasia Foundation, believes that politics should not play any role in such decisions.

“When the relations between two countries have been worsening and when Americans find it difficult to work in Russia, on the contrary, the U.S. should place its bets on an increase in student exchange programs,” Kortunov said.

He noted that after the closure of the USAID office in Moscow, many educational agencies and funds encouraged Russian students to visit the U.S. in an effort to counter stereotypes about the United States and Americans.

When asked about the Summer Work and Travel case in particular, Kortunov said that the program requires more control from officials.

“The Work and Travel program is a tool for Russian students to come the U.S. [easily] and it is not always possible to control,” he said. “It’s no secret that many Russian students became illegal migrants in the U.S. Sometimes they happened to come in an unfavorable environment and their expectations didn’t come true.”

But he nevertheless warns against closing the program altogether.

“It’s not in U.S. interests to shut down such a program,” he said. “And I hope that program will exist and its efficiency will be only increased.”

Alumni of the program, however, argue that increased scrutiny of applicants is the wrong path to take.

“I can't imagine myself getting a job in a program these days, when the rules are a lot tighter than three years ago,” said Stepan Serdyukov, who visited the U.S. as a Summer Work and Travel student in 2010.

He called his experience “life-changing and character-building.” Serdyukov said the program has “a slow but deep impact on a society” as well as on its participants, who “may have a clearer view of what a civil society looks like and how important liberty is to economic prosperity.”

“Almost everyone with a fair grasp of English could benefit from the program, and not only in the terms of money earned: A complete immersion in a foreign culture, a foreign immigrant worker culture is something priceless,” Serdyukov said.

Anna Laletina who was a Summer Work and Travel participant in 2009 working as a housekeeper in a motel in upstate New York and later in a local McDonalds wasn’t as positive about the experience as Serduykov, but was still happy for the opportunity.

“I had already been to the U.S., so I knew a lot and I knew what to expect,” Laletina said. “Yes, it was interesting though to work in such environment where we worked. I am glad I did that. When in my life would I do such a thing again?”

Moscow State University student Vladimir Chukov who lived and worked in New York said that he came back from his Summer Work and Travel experience “a completely different person” and that it helped him build his problem-solving skills.

Vladimir Chukov's expereince as a Work and Travel participant. Source: VChukov / Youtube

Serdyukov is ready to attribute the increase in visa rejections to politics. “The embassy employees see that the political climate in Russia is getting harsher by the day, and so they may grow overly suspicious about every young person trying to cross the borders with a work visa, because they understand that a life in the U.S. might be a very tempting perspective,” he said.

Laletina had a different perspective, however. “Maybe the U.S. government thinks that within the U.S., the unemployment rate is so high anyway that they don't really need additional people who want jobs,” she said.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox