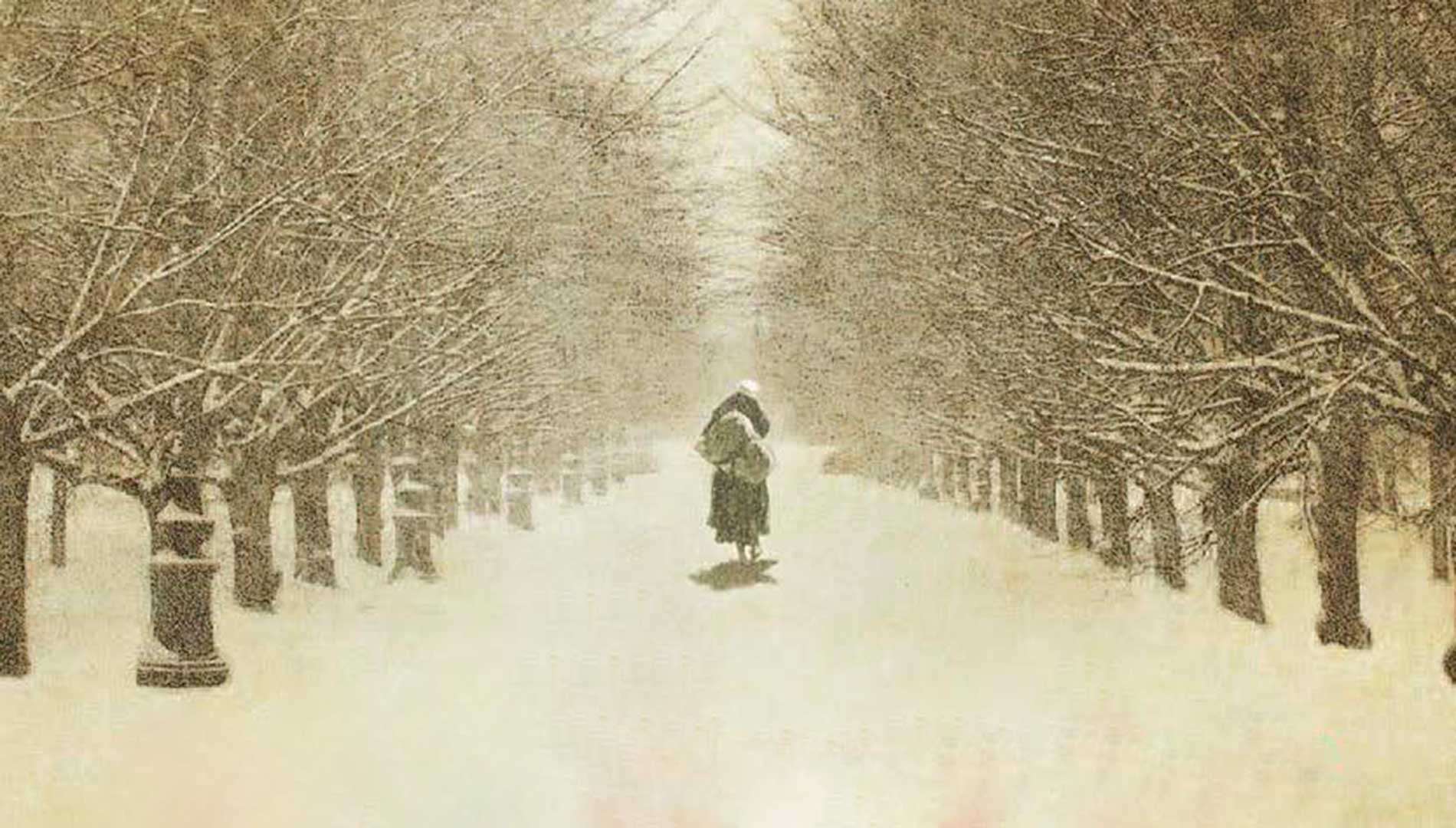

The road to Stalin’s wartime camps: A grandson’s journey following his babushka’s footsteps

Cilly and Marcel, early 1980s

Courtesy of Marcel KrügerWe all listen to our grannies’ stories when we’re young, sometimes hundreds of times over. German Marcel Krüger listened to his granny – called Cilly – countless times while she recounted tales of being taken by Red Army soldiers and sent to remote Soviet camps just months before Nazi Germany was defeated. The descriptions of people being squeezed into train carriages like cattle, harsh Siberian winters, and prisoners shedding pounds and pounds are etched into his mind.

After Cilly passed away, Marcel didn’t want her stories to be forgotten so he decided to journey to Russia and follow in her footsteps. “I never wrote down her stories when she was alive, but now, after she’s gone, I cannot leave them alone. It’s about preservation, isn’t it?” He also wanted to commemorate all the hundreds of thousand people who were deported to Soviet labor camps, many of whom died there, and many remain unknown. So he wrote a book titled Babushka’s Journey: The Dark Road to Stalin’s Wartime Camps about both his own journey and Cilly’s everyday life in the camp.

The road to red Russia

First Marcel visited Allenstein where Cilly was born. It was an East Prussian city once under Polish rule, it was also a German enclave in Poland. After WWII the city was returned to Poland under the name Olsztyn. As a

So it makes it even more unfair that Cilly’s mother was among those chosen to be deported as a prisoner of war by the Soviet army in February 1945. But Cilly chose to go instead of her mum, saving her.

Marcel tried to ask locals in the hope that someone would have remembered the events, but almost everyone was unwilling to talk. However, he did manage to track down a witness.

“The soldiers told me to pack my things for two days...They called out our names, put us in groups of 30 to 40 and packed us into livestock wagons,” Frau Moritz told Marcel. “For three weeks we traveled eastwards, with them throwing in food, dry rusks

Marcel in Moscow

Courtesy of Marcel KrügerMarcel’s stopped off in Warsaw before traveling to Moscow. He grew up hating all things Soviet, most of all the “mustachioed man” Joseph Stalin, whom he considers the most evil after Adolf Hitler. So Marcel expected to see red flags and monuments to Stalin all over

He was surprised to find a modern city and Russians who reflected on their past thoughtfully - who have nothing in common with the NKVD officers who grabbed his grandmother.

Gulag memorial by Evgeny Chubarov in Muzeon Park, Moscow

Courtesy of Marcel KrügerTrain experience: Romance or nightmare?

Marcel rode many trains, just like his granny. Every minute of his journey he tried to imagine Cilly being carted to the labor camps – not in comfortable wagons with to tea and fresh bed lines, but in cramped trains with only a hole in the side for a toilet, and the ever-present fear of dysentery, as there were no washing facilities. From

After soaking up some of Russia’s nature through the train window, Marcel thought it was sad he didn’t arrange any visits to lakes or picturesque countryside. But he then realized Cilly wasn’t afforded such luxuries – would she have enjoyed nature while slogging her guts out chopping wood in local forests under the eagle eyes of Soviet guards?

Camp hell

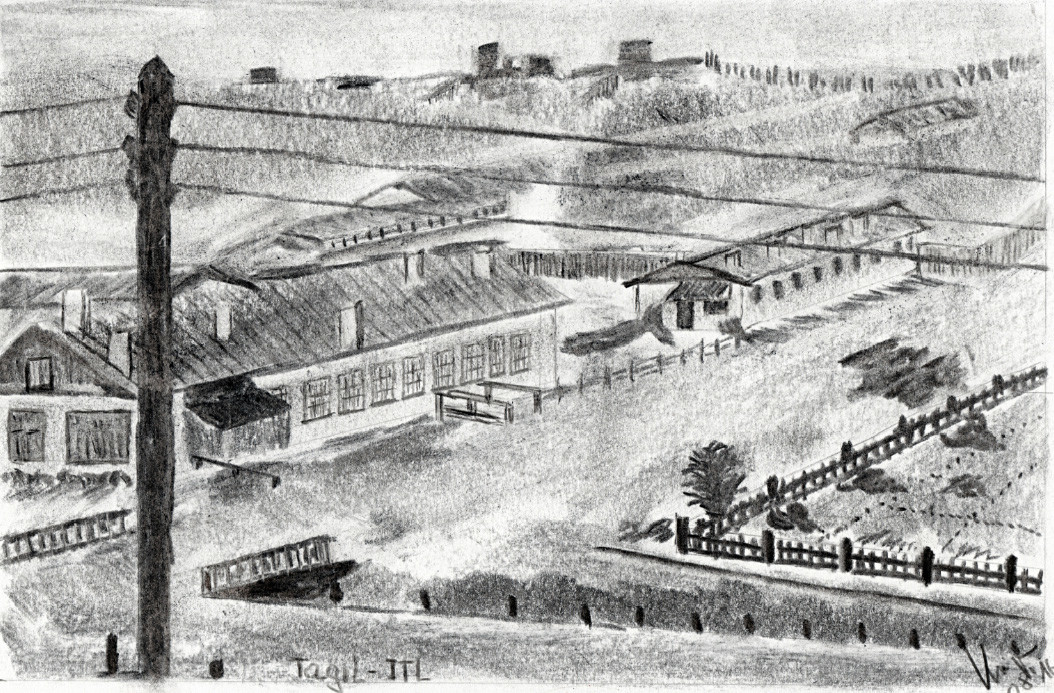

Camp in Nizhny Tagil

Courtesy of Marcel KrügerBefore the

During her time in

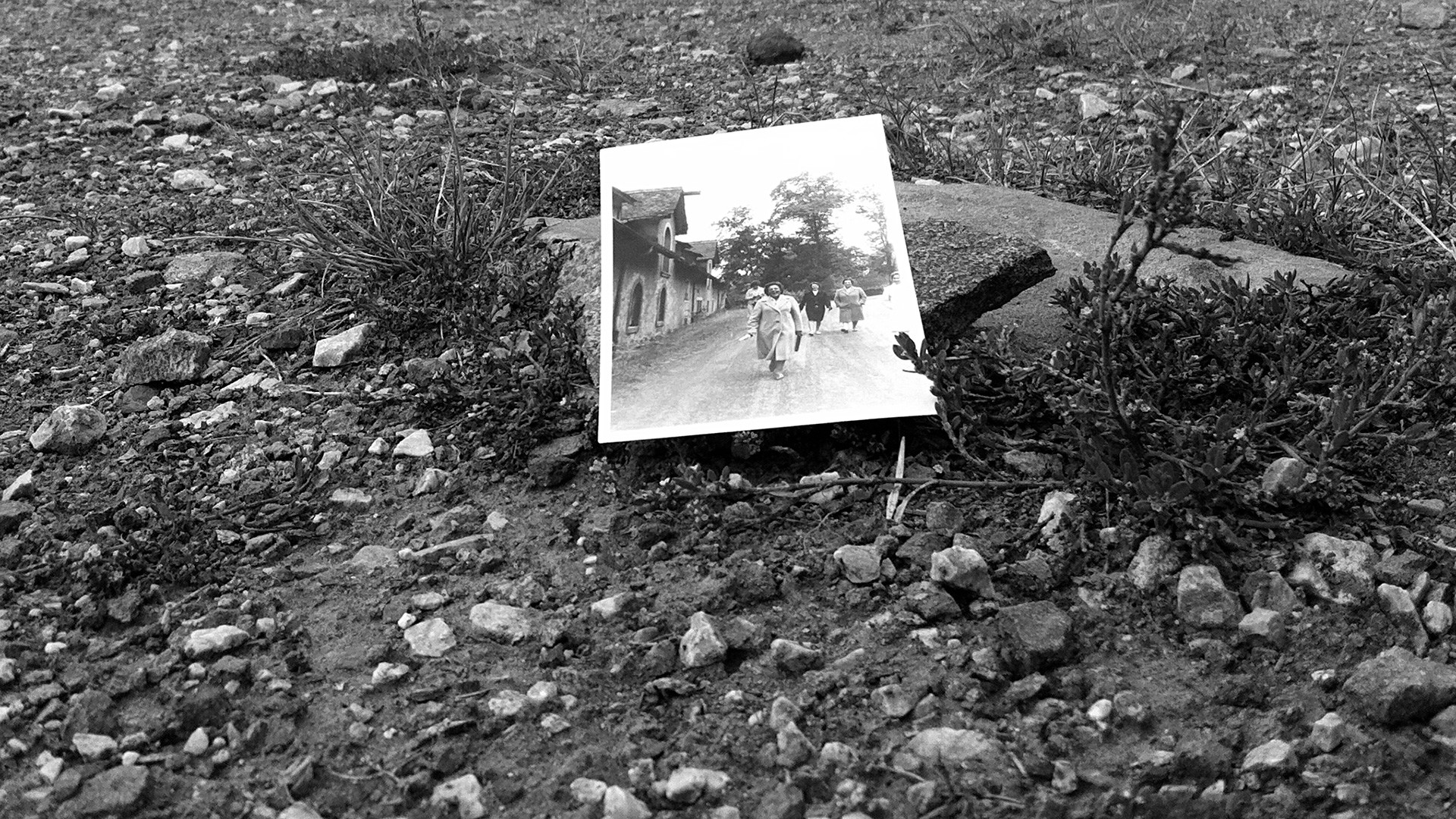

Image of Cilly on a street in the Urals

Courtesy of Marcel KrügerWhat did the journey actually mean for Marcel?

In his narrative, Marcel interweaves his grandmother’s story and his own journey, so now he understands what Cilly went through and the stress her mind and body were forced to endure. He now also realizes why his granny was so fond of chocolate and milk.

Cilly at a health resort in West Germany

Courtesy of Marcel KrügerFor the last two years of

Read more: 7 quotes from Varlam Shalamov’s ‘Kolyma Tales’ that will give you chills

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox