How did a 19th century German businessman create Russia’s most popular chocolate?

Paradoxically, the chocolate that became one of Russia’s most recognized brands was originally produced in a factory established by a German immigrant who came to Russia at 25 years old, full of hopes and dreams. In 1849, this adventurous man already was the chocolate supplier to the Imperial

So, he started his own mass-production enterprise, opened his first chocolate factory on Myasnitskaya Street in the city center, producing sweet delights of the highest quality that previously were only imported to Russia from Europe. In 1851, the young entrepreneur opened his first small shop on Arbat Street. Einem chocolates started to gain popularity in Moscow.

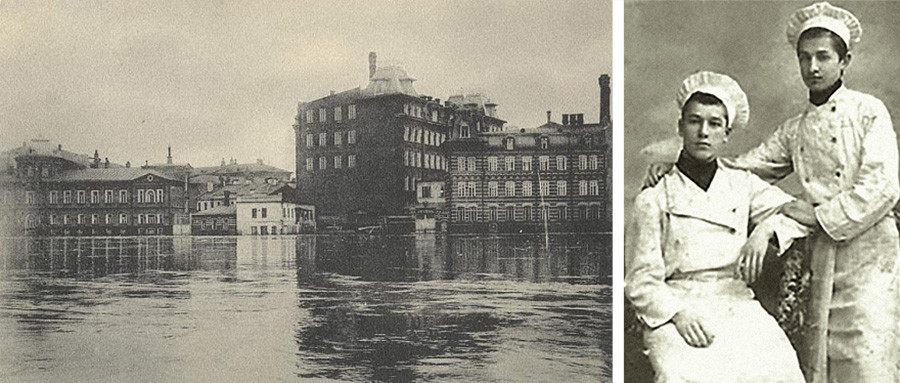

View of the Krasny Oktyabr confectionery.

Vladimir Vyatkin/SputnikLater, he founded a business with his partner and compatriot, Julius Geis, and together they opened their first chocolate production plant on Sofiyskaya Embankment. In 1876, Einem died in Germany, but according to his final will and testament, he was buried in Russia. Geis took over management of the

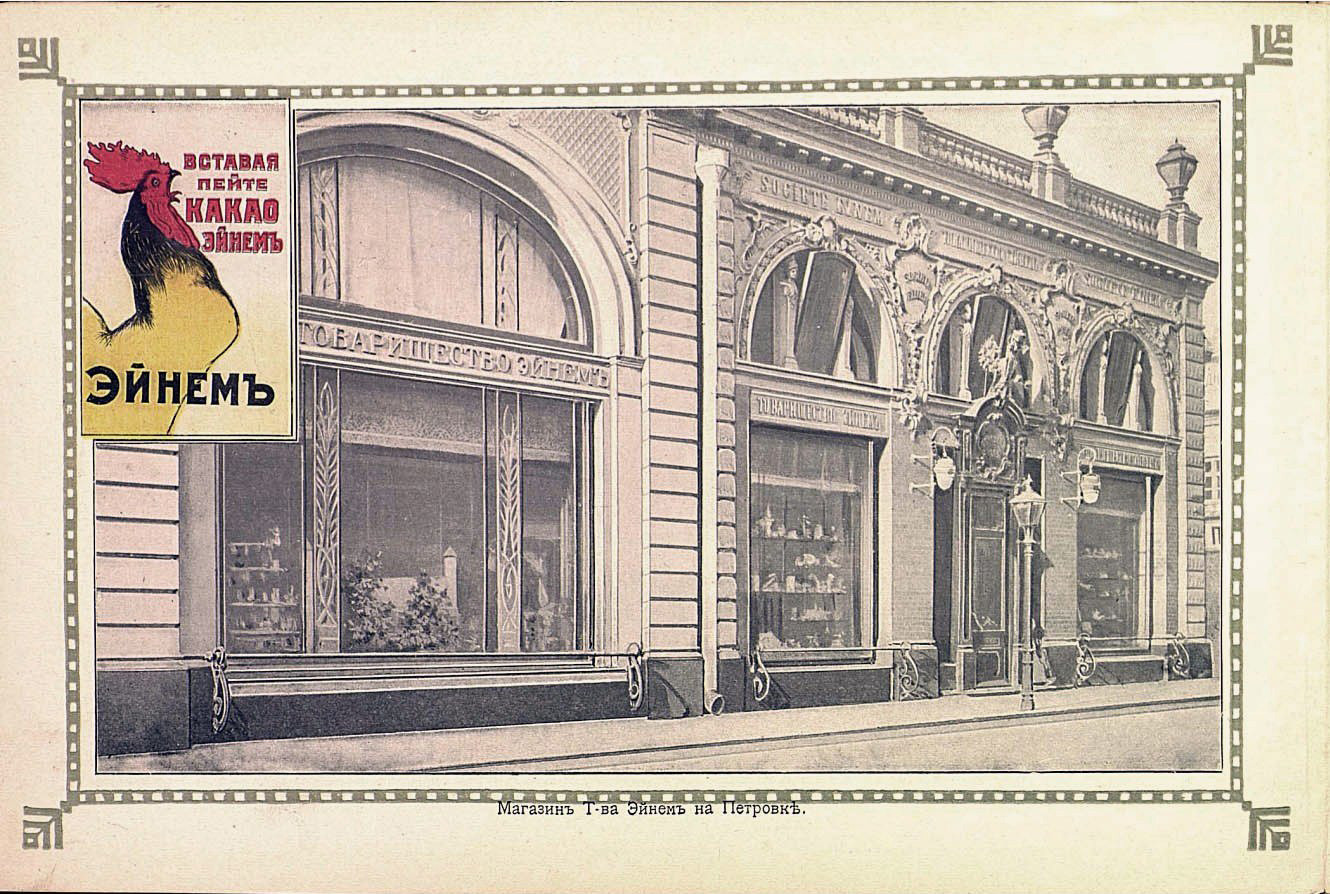

Einem shop on Pokrovka street.

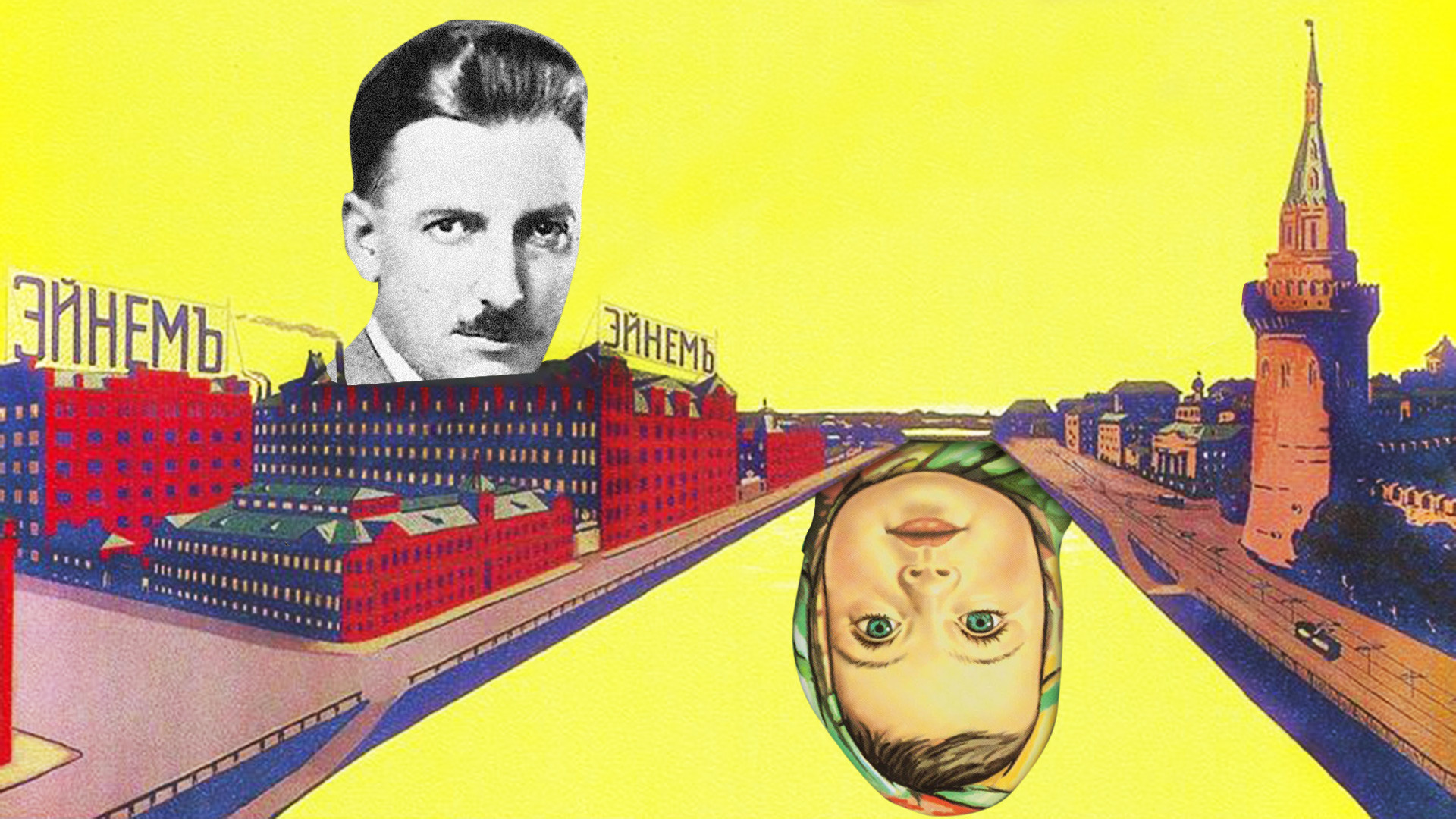

Archive photoIn 1889, Geis purchased land on Bersenevskaya Embankment in order to establish a huge 23-building factory. The company stayed in this monumental red brick complex until 2007 when the factory was relocated. It was perhaps the most recognizable company in the Moscow center, close to the Kremlin.

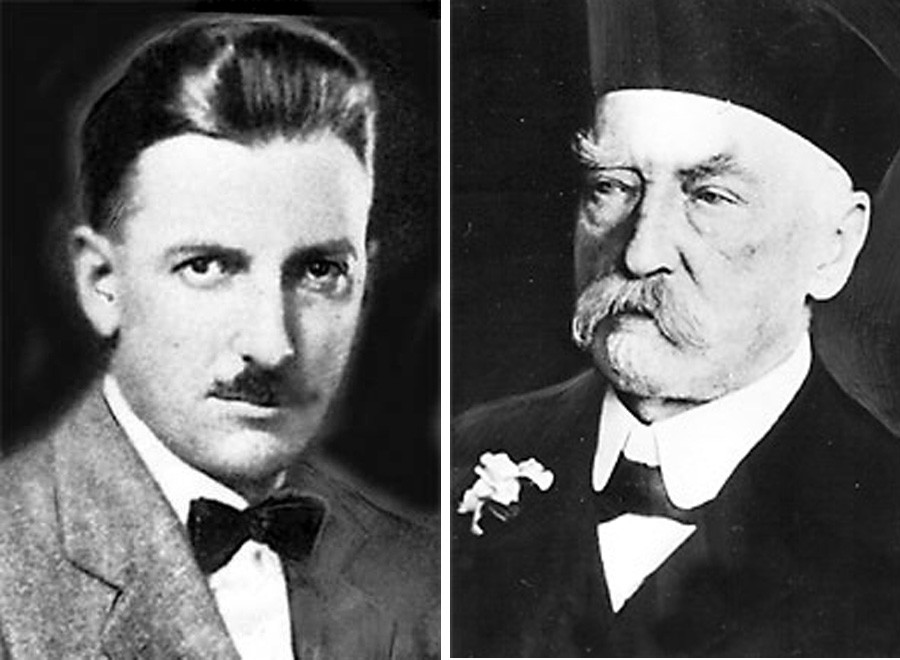

Ferdinand Theodor von Einem and Julius Geis

Krasny OktyabrThe Einem Chocolate Factory became the Imperial court supplier in 1913, establishing branches and shops in Simferopol, Riga and Nizhny Novgorod, as well as earning prestigious national and international prizes for its quality and assortment. One of the reasons for the company’s success was its innovative marketing strategy.

Futurist marketing

Believe it or not, but in an era when marketing did not even exist Einem’s company took seriously not only the quality of chocolate (the level was so high that it could compete with chocolates from Belgium, Holland or France

Special music was composed by Karl Feldman for the company’s shops that included creative dedications to chocolate products: consumers had the opportunity to buy musical notes for the Waltz-Montpensier, Cupcake Gallop or Cocoa Dance, which were played in the shop by trained professionals

Creativity flourished as soon as one opened the box: a series of collection cards showed futuristic Moscow, paintings of Russian artists, national costumes, birds or butterflies usually awaited the surprised candy-lover. By collecting a certain number of cards, consumers had the right to a free box

The State History Museum. The exhibition "Krasny Oktyabr" devoted to the 150th anniversary of the oldest confectionary plant which was called "Einem" before the revolution of 1917. Box in which sweets and biscuit made by "Einem" were sold.

Dmitry Korobeinikov/SputnikAnother marketing innovation was brand-name chocolate vending machines that sold products. Small chocolate bars could be bought by putting a 10-kopeck coin into an automatic machine and moving the lever. They became very popular, creating an endless temptation for children.

High salaries and workers’ benefit

Probably the factory’s most successful business strategy was the enlightened attitude toward its workers: they had good working and living conditions, as well as work-life balance (if it’s possible to talk about this at the end of the 19th century).

Imperial era factories in Russia reaped enormous profits by exploiting their workers: standard shifts for workers frequently lasted 15 hours, starting at 4 a.m. and ending at 9 p.m., with a few short breaks, and all this in an unhealthy environment and lacking civilized working conditions

Salaries were the highest in the industry, starting at a minimum of 20 rubles and growing two rubles per year. Workers who stayed with the enterprise for 25 years were awarded a silver medal and a pension equivalent to their salary. This was unprecedented for that

Charity and supporting the war effort

Einem hospital, 1914.

Krasny OktyabrDuring the First World War, Einem made significant donations for the benefit of those

The factory did everything possible to help tackle the crises that the country found itself in after the start of the war.

A new life after the 1917 revolution

While the Einem factory was nationalized after the Russian 1917

Apart from the many successful enterprises that were ruined by the upheavals of the revolution, Einem, in the form of Krasny Oktyabr, was like a phoenix rising from the ashes, and continued its production, beating out records set during the Imperial era.

"I eat cookies from the Red October factory, the former Einem". Text by Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Archive photoDuring the Second World War, the factory concentrated its energy on the production of goods for the front, and it made sweets for pilots and soldiers that had special ingredients and vitamins in order to keep those men strong and awake for much longer periods of time.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the factory was privatized and was merged into a holding that includes its long-term competitors, such as Babaevsky and Rot Front chocolate and

Eternal branding

The factory managed to preserve the quality of its goods both before and after the revolution, and it created chocolates that are inextricably linked to Russian culture and mentality.

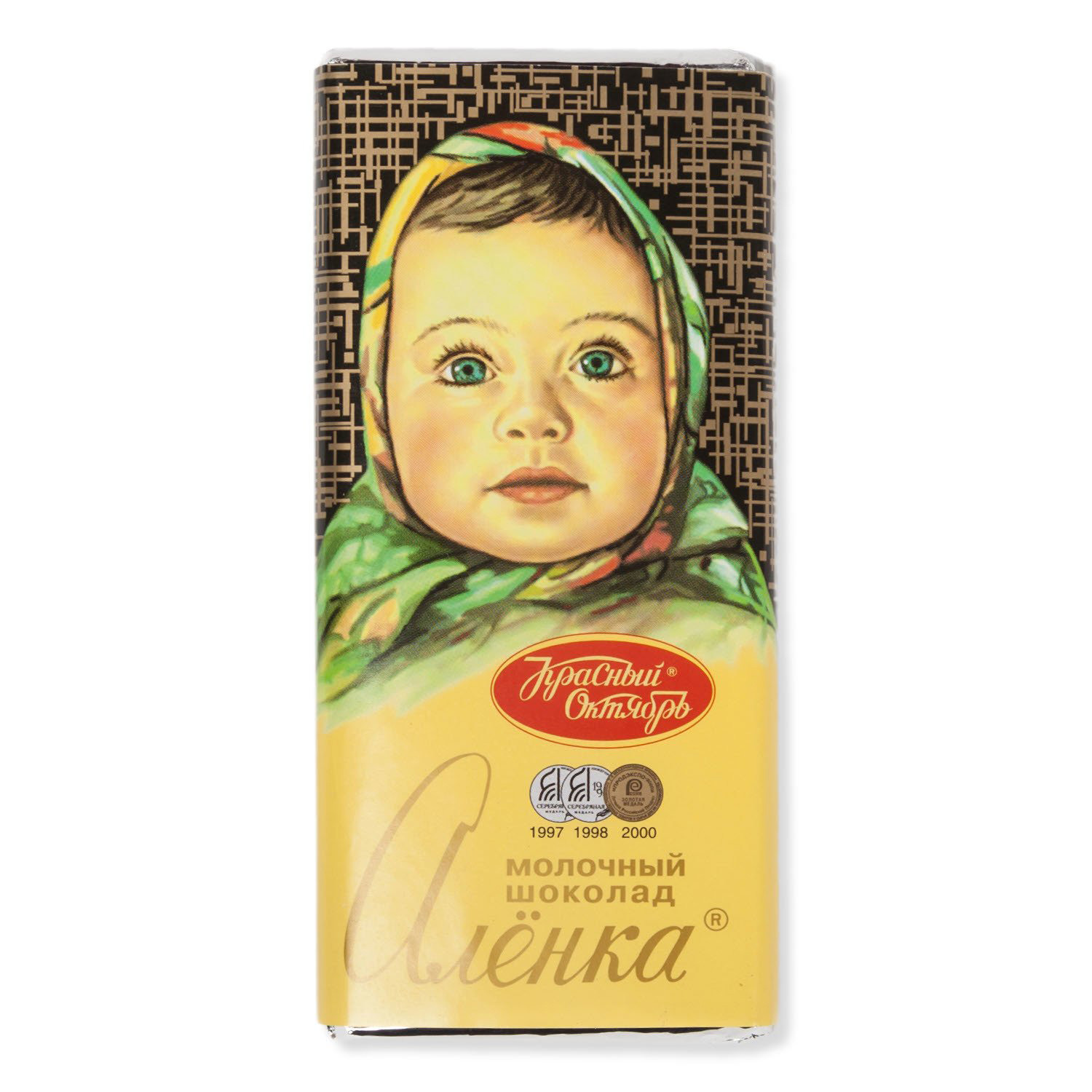

Alyonka is a great souvenir to bring from Russia, and this chocolate is illustrated with a beautiful little girl in a traditional Russian scarf. How was it created? One of the artists working for the factory decided to depict his adorable little daughter in 1965. Her image still remains the well-recognized brand of the factory and the Russian chocolate industry as a whole

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox