American jeans were a dream for almost every Soviet person. And, for a long time, it was a barely feasible dream.

For the first time, the citizens of the USSR saw jeans en masse at the end of the 1950s: about 34,000 foreigners came to the country for the World Festival of Youth. From that point onward, according to the words of fashion historian Megan Virtanen, they didn’t just become a prestigious Western commodity for Russians, they turned into a fetish.

Sixth world festival of youth and students in moscow, July 28, 1957

Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesHere are some examples of what lengths Russians were willing to go for a pair of such jeans.

Students were ready to work at night, unloading train cars, to acquire them – Levi’s, Lee, Wrangler or Montana jeans back then cost anywhere from 150 to 300 rubles (equal to 3-4 most monthly salaries).

People faced getting expelled from university or fired from work for wearing them and youngsters were simply barred from school – but people, nevertheless, took such risks, too. Having acquired jeans, some wore them every day for 3-4 years straight, simply staying at home if the jeans needed washing.

There were also tragic episodes: at the end of the 1970s, ‘Literaturnaya Gazeta’ (‘Literary Gazette’) reported cases of teenagers committing suicide, because they didn’t own this fashionable item.

For a while, the USSR officially fought against wearing jeans – there was no original American denim for sale on store shelves. ‘Fartsovschiks’ – people who peddled foreign goods, including jeans, sometimes with up to a 300% markup – were persecuted as speculators (speculation was a criminal offense).

However, the more the Iron Curtain was lifted, the harder it became for the state machine to resist the popularity of the foreign product. In the end, Soviet authorities decided to use this demand to their advantage.

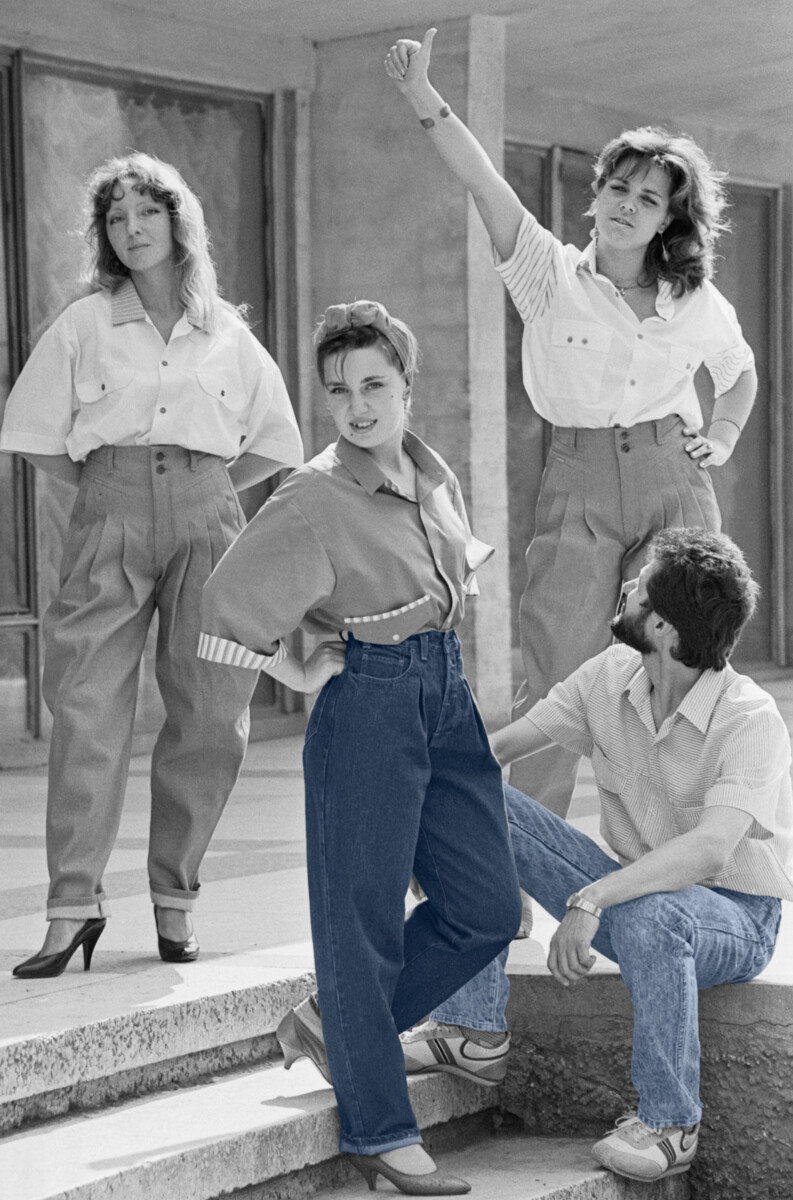

In the 1980s, the Soviet light industry decided to produce the popular item by itself with a Western license. But, they couldn’t come to an agreement with famous brands. Then, they turned to Italian brand ‘Jesus Jeans’. With their license and equipment, the USSR began sewing its own jeans for the first time in 1983 under the brands ‘Tver’ and ‘Vereya’. The production output was colossal – 1.2 million pairs per year.

However, there was a problem with them: although they were called jeans, they were only similar to them in color at best. They were sewn not from real denim, but from an imitation – thick cotton of poor quality. This type of material didn’t “age gracefully” like denim – with necessary fading – instead, even after just 10 washes, it simply lost color and tore. Despite this, Soviet jeans were still swept away from shelves. To make them look like imported jeans at least somewhat, they were artificially worn down with pumice (producing the same fade like with real denim). A washing machine was run with a piece of pumice and jeans in it.

Aside from that, in the 1980s, jeans with “marbling” came into fashion in the West, which made enterprising Soviet people very happy. Because they knew exactly how to imitate this effect. That’s when people began boiling jeans en masse.

The method was effective and required a creative approach. Before boiling the jeans, they were twisted and tied up, secured in this position with clamps. The type of clamps affected the shape of the marbling.

Then a large pot of water was put to heat, adding large amounts of bleach to it (approximately 1:5). Twisted jeans were placed into the pot and boiled for 15-20 minutes, stirred with a long spoon. After that the item was thoroughly rinsed. Bleached marbling, imitating the original, was the result. In the USSR, they were called ‘varyonki’ (“boiled”) jeans.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox