Sarov is located in Nizhny Novgorod Region, 370 km east of Moscow. Just under 100,000 people live in it and its population is strictly limited. It has been a closed town for many years and even people who live in the region can't easily go there.

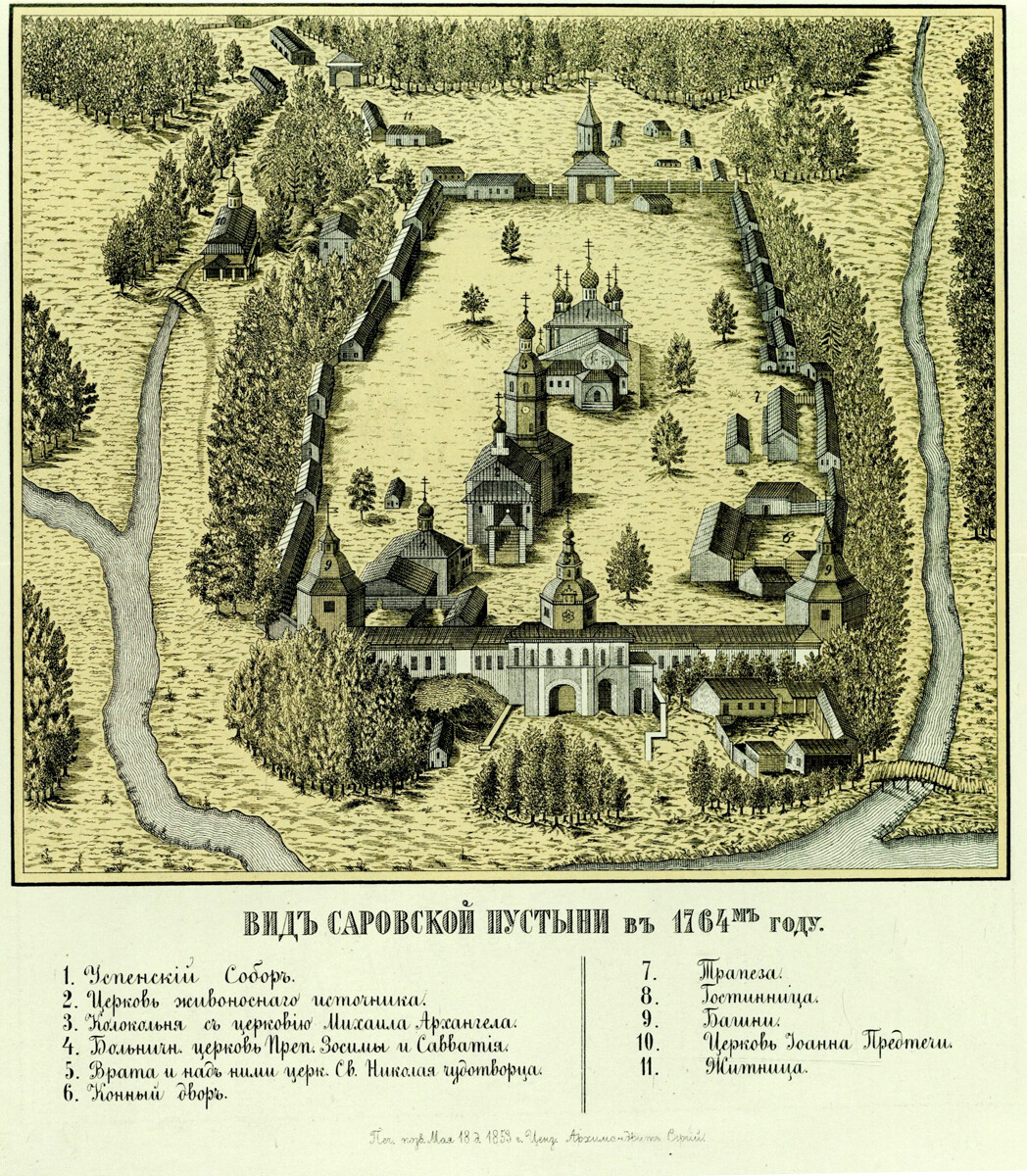

Sarov sprang up on the River Sarovka back in 1706, but it was not immediately a closed town. Before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution it was a settlement popular with pilgrims – the famous monastery of St. Seraphim of Sarov was located there.

After World War II, the small settlement in the remote wilderness attracted the attention of the Communist Party: It decided that the settlement surrounded by swamps was an ideal place for secret facilities. In 1946, key facilities for research into and development of nuclear and thermonuclear weapons (the most important one of which was named ‘KB-11’) were moved to Sarov. Warheads for aerial bombs, cruise missiles, torpedoes and intercontinental ballistic missiles were also made there and the settlement itself became classified as top secret.

Sarov was not just closed off to ordinary individuals, but also “deleted” from Soviet maps and excised from all the gazetteers of the country's administrative divisions. Meanwhile, employees of secret enterprises and their families still live there today. You can only go there after obtaining a special permit from the authorities or at the invitation of a relative resident there. Tourists, dual nationals and people convicted of serious offenses under the Criminal Code are barred from entering.

"Even people from the CIS republics can't come to Sarov for work. In other Russian towns, they do unskilled and low-paid work, while, in Sarov, this category of jobs is performed by residents of neighboring population centers. Each day, starting at 6:00, around 4,000 people enter Sarov for work; they need to leave the town by 22:00 or they will end up breaching the regulations," Aleksei Golubev, the head of the town administration, told 'Kommersant' newspaper in an interview.

The developers of the first Soviet hydrogen bomb – academicians Andrei Sakharov and Yuli Khariton, as well as the USSR's most hush-hush academician, Yakov Zeldovich – lived and worked in the town.

Throughout the post-war years, the town and its strategically important workers were kept so successfully hidden, that this was reflected in the town's names. It had six altogether.

After 1946, Sarov had a large number of codenames: It was variously referred to as ‘Obyekt-550’ (‘Site 550’), ‘Baza 112’ (‘Base 112’), ‘Privolzhskaya Kontora Glavgorstroya’ (‘Volga Office of Glavgorstroi’) and ‘Kremlev’. And, in 1954, in line with a decree on the establishment of secret centers of population, Sarov became the town of Kremlev.

Six years later, however, it was renamed again and became ‘Arzamas-75’. These sorts of names with code numbers became the most commonly used designations for closed towns on Russian territory. The numbers themselves, however, were completely meaningless (there weren't another 74 secret ‘Arzamases’).

But, given that this was the case, the code could betray the identity of a secret town and the name came under a lot of criticism from the authorities: Arzamas, a perfectly ordinary non-secret town, did, in fact, already exist and was located 75 km from Sarov. It was claimed that the coincidence was purely accidental, but it was still decided to change the name, just in case.

Six further years later, in 1966, the town became ‘Arzamas-16’ and bore this name until 1994.

In 1994, with the USSR having already disintegrated, it was decided to restore the name of Kremlev to the town, but the name change lasted just a year. In 1995, it was called Sarov again and bears its historical name to this day.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox