Advice on how to act in a crowd

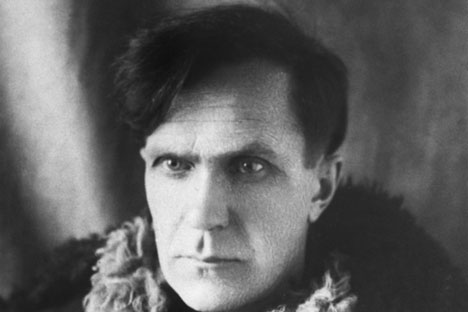

Soviet writer Varlam Shalamov. Source: ITAR-TASS

When Varlam Shalamov rejected Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s offer to co-author the Gulag Archipelago, he sparked a conflict between the two on the question of whether suffering is redemptive and what role art should play in society.

Solzhenitsyn once asserted that “literature becomes the living memory of a nation” and the inclusion of The Gulag Archipelago onto Russia’s high-school curriculum confirms that one can apply this statement to his own works.

The same cannot be said for his contemporary, Varlam Shalamov, who survived 17 years in the same camp system, wrote as powerfully and brilliantly as Solzhenitsyn, and yet has garnered little recognition within Russia or abroad.

For anyone interested in the experience of the Gulag, Shalamov’s collection of short stories Kolyma Tales is an absolute necessity, forming a complement to Solzhenitsyn’s work due to the writers’ contrasting styles and philosophy. John Glad, who produced the first translation of Kolyma Tales, writes in his foreword that the reader is “a person whose life is about to be changed.” This can be seen as a kind of disclaimer, a warning that this material is not for the faint-hearted, with its unflinching presentation of the brutality of power and the range of human suffering. Shalamov wrote that “a writer must be a stranger in the subjects he describes” and his work is defined by his direct, objective, presentation of suffering, with the detached gaze of his narrators serving to bring the subject matter into sharp relief.

Thematically, each of the stories is self-contained, focusing on a different element of camp life, a specific event, or a personality. However, this thematic division masks a deeper artistic unity. Critic and translator Robert Chandler notes that “whole passages are sometimes repeated between stories, but the story will end differently.” For Chandler, this creates the impression that Kolyma Tales is like a mosaic that has been shattered, and intentionally so, as if to exemplify the fact that the experience of the Gulag does shatter one’s world.

Thus Shalamov was not embarking on a historical project, and does not provide the reader with the expected eyewitness testimony in the mold of Auschwitz survivors such as Eli Wiesel and Primo Levi.

Shalamov declined to collaborate with Solzhenitsyn in part because he was disinterested in an historical approach, and in part due to his differing philosophical outlook. He claimed that “Solzhenitsyn is bogged down in the themes of nineteenth-century literature” and “all those who follow Tolstoy’s precepts are cheaters.”

Varlam Shalamov's profile

Born: June 18, 1907, Vologda

Died: January 17, 1982, Moscow

Education: Moscow State University

Occupation: Writer, journalist, poet

Notable works: Kolyma Tales, Graphite

Time spend in the Gulag: 1929-1931, 1937-1951

He believed that “art has lost the right to preach” and seems to suggest through his writing that no greater good could emerge from the Gulag. Thus in sentences such as “I felt a strange and terrible pity at seeing adult men crying over the injustice of receiving worn-out clean underwear in exchange for dirty good underwear”there is no sense of a deeper moral imperative at work, just a sparse yet intensely emotional presentation of humiliation and degradation.

Shalamov’s central question is what sustains and drives humans, giving us the capability to survive experiences such as the Kolyma camps. One of his narrators says that “a human being survives by his ability to forget, memory is always ready to blot out the bad and retain only the good” while another, who stumbles on a children’s picture, is moved by happier childhood memories which momentarily distract him from his situation. Such bittersweet moments punctuate the otherwise bleak narratives. In the story “Sententious,” the mere memory of one word brings about unbridled joy to a man whose language and memory have been all but crushed.

Shalamov examines the notion that humans require more than just survival on a physical level, touching on the soul’s spiritual requirements through lines such as “needing more than bread, / I dip a crust of dry sky, / in the morning chill, / in the stream flowing by.” In a series of notes “What I’ve seen and learned at Kolyma camps, Shalamov” concluded that “the extraordinary fragility of human nature, of civilization” is his most important lesson.

Shalamov consistently downplayed the profundity of his work, claiming “my stories are basically advice to a man on how to act in a crowd.” This statement is typical of an unassuming writer who deserves wider recognition for his contribution to literature.

During the course of Stalin’s purges, which reached their peak in the period 1936-1938, more than a million ordinary people and intellectuals were arrested on trumped-up charges and sentenced to hard labor. The charges were usually vague and the terms unreasonably harsh.

Notable sentences:

Alexander Solzhenitsyn [writer]: eight-year term for making “derogatory comments” about Stalin.

Varlam Shalamov [writer]: 10 year term for describing Bunin as a “classic Russian writer.”

Vladimir Petrov [academic]: six-year term for “possession of counter-revolutionary literature” – diaries written when he was 16 years old.

Nikolai Getman [artist]: eight-year term for “participating in anti-Soviet propaganda” after drawing a caricature of Stalin on a cigarette packet.

Sergei Korolev [rocket engineer]: 10 year term for “slowing the work of the research institute.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox