A land of stories

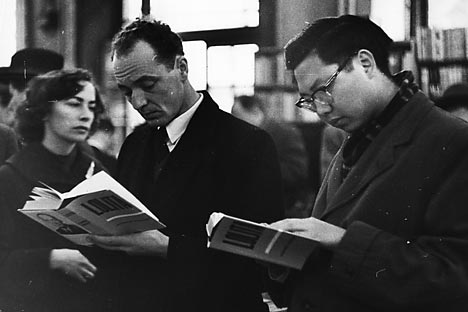

People reading Lolita of Vladimir Nabokov. Source: Getty_Images / Fotobank.

Among this year’s publications, there are dozens of new books about Russia or set in the country. Geopolitics, energy, photography, education, literature and architecture: writers and academics are considering and re-considering numerous aspects of Russian life. But above all, 20th- century Russia is seen as a source of stories, of human ingenuity and unforgettable settings; of war and peace, siege and gulag, of life in palaces or communal apartments.

Art and soul

Novelist, Sarah Quigley, was New Zealand’s number-one bestselling author for several months with her mesmerizing tale of Shostakovich in wartime Leningrad, “The Conductor” (Head of Zeus, 2012). The idea for the novel came from a chance encounter with a Russian piano dealer in Berlin. Through him, she met the singers and musicians who told her the story of the Leningrad Symphony. With detailed research and her own musical background, Quigley has risen to the challenge of creating an emotionally realistic historical novel.

Related:

Russia's emigres write East and West

Telling Russian stories in English

A Russian export "better than sex" and more valuable than oil

The composer’s struggles to write music against the backdrop of roaring planes are convincing. Quigley imagines how the notes of the symphony relate to his biography: the oboe in the scherzo, lilting and soaring, was “Tatyana’s voice as it used to be, before she became quarrelsome and possessive.” The novel’s hero is not Shostakovich, but the lonely conductor of the ragged remains of the Radio Orchestra, Karl Eliasberg. Son of a cobbler, living with his dying mother, he drags himself heroically through the starving streets to rehearsals.

Like the symphony itself, “The Conductor” builds slowly to its climax. The novel achieves its full power in the final moments, “poised on the edge of silence.” Quigley introduces a fictional violinist called Nikolai, grieving for his lost wife and daughter. His tear-jerking tale contrasts with Eliasberg’s stoic impassivity.

The Leningrad Blockade has become a familiar novelistic setting. Helen Dunmore’s “The Siege” (reissued by Penguin in 2010) recreates the same terrible winter of 1941, filling the air with the smell of burnt sugar after the Germans bombed the food storehouses; Debra Dean’s “The Madonnas of Leningrad” (Harper Perennial, 2007) inhabits the story from the point of view of a Hermitage tour guide, recalling details of paintings that have been stored for safekeeping. Quigley, like her predecessors, hints at the grimmest realities of starvation. Eliasberg boils down his briefcase; others survive on rats or human flesh, but the musical element to the novel lifts it above the horrors of the survival story; this is a tale of human resilience and the power of art.

Imperial myth-making

Writers gravitate to the potent mix of creativity and suffering they associate with Russia. Dora Levy Mossanen’s new novel “The Last Romanov” (Sourcebooks, 2012) is no exception. Set in late imperial Russia, spiced with “Rasputin’s magic and Romanov mystery,” heaving with Caspian caviar and herb-scented vodkas, steamy samovars, bejeweled Faberge eggs and ballets at the Marinsky, Mossanen’s fantasy is unashamedly implausible. The details of hunting parties, or the cupolas of Petersburg in the unending light of the “White Nights,” are mythologized as freely as Arthurian legends.

These familiar elements are stirred into a tale of magical realism involving lost princes and portents. One of the novel’s epigraphs is a line from Nabokov’s “Lolita” about immortality: “I am thinking of aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments, prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art.” Besides an overflow of jewelry, costumes or cuisine, Russian paintings are used as a backdrop, from icons through to “modern masterpieces by Chagall and Kandinsky.” And, of course, there is suffering too: Tsarevich Alexei’s hemophilia, Prince Yusupov’s gory murder of Rasputin, the chaos and brutality of revolution. Mossanen’s reveling in and romanticizing of this period of Russian history is reminiscent of Simon Sebag Montefiore’s ill-advised foray into fiction with “Sashenka” (Corgi, 2009).

Looted palaces and displaced plutocrats

Historian Douglas Smith has also been studying the “looted palaces and burning estates” of post-Revolutionary Russia. The theme of his previous book, “The Pearl” (New Haven, 2008), was the romantic story of the relationship between Count Nikolai Sheremetev, richest aristocrat in Catherine the Great’s Russia, and the serf opera singer, Praskovya Kovalyova (nicknamed “Pearl.”) Smith’s latest book, Former People (FSG, 2012), which is due out in October this year, also focuses on the Sheremetev family along with others in the “Final days of the Russian Aristocracy.”

Smith never pretends to be totally impartial. He first met descendants of Nikolai and Praskovya’s in the course of researching “The Pearl” and was struck by how far the fate of the Russian nobility in the early twentieth century has been ignored. Smith attempts to fill the gap by charting not only tales of aristocratic “imprisonment, exile and execution,” but also the survivors’ struggles to find a place for themselves in the Soviet Union. He even argues that the destruction of an entire class foreshadows later 20th-century atrocities “from Hitler’s Germany to Pol Pot’s Cambodia.”

The “Former People” of the title are the displaced aristocracy, seen by the Bolsheviks as “obvious class enemies,” “vermin” or snakes. Vladimir Trubetskoy introduced himself in 1960s Paris as “a former prince from Moscow.” Toward the end of the book, Smith describes meeting Vladimir’s grandson, Nikolai Trubetskoy, in Moscow. The aristocratic feasts of his ancestors have been replaced by Caesar salad and fizzy water in a branch of TGI Friday. This kind of shift and contrast between counts, communists and businessmen is part of Russia’s fascination, producing a flood of histories in recent years.

Love in the Gulag

Related:

Orlando Figes’ latest book, “Just Send Me Word” (Penguin, 2012), leaves the epic scale of “The Whisperers” (Penguin, 2007) to focus on two individual lives in Stalin’s Russia. Lev Mishchenko was serving a ten- year sentence in Pechora “deep in the forests near the Arctic Circle,” while Svetlana Ivanova worked in post-war Moscow. Figes got access to a trunk full of their personal letters and wisely lets the Mishchenkos tell much of their own story. The result is a moving evocation of love and courage in a brutal time. From the agitation of Lev’s reply to his first letter from “Sveta” through to their eventual reunion, they promise each other, “We’ll get through this.” Lev’s nostalgia for autumnal Moscow “a golden season where leaves fall” is matched by Sveta’s realism: “People are irritable … the metro is always full.”

Lev stoically celebrates the beauty of the northern lights, even as he mourns their long separation. “I will regret every greying hair on your head”, he tells her, but “you will always be my Svet, my light” (Svet means light in Russian). Their letters were smuggled in and out of the camp and as Lev’s become gradually more honest and unguarded, they provide an intimate, real-time portrait of gulag life, from eating pine needles to ward off scurvy to the soul-destroying details of the charges against him.

Irina Ostrovskaya, senior researcher at the human rights organization, Memorial, has described the letters as “a unique archival treasure revealing a hidden world of emotions.” When Figes read out some of the letters at the Hay Literary festival in Wales this summer, several members of the audience wept.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox