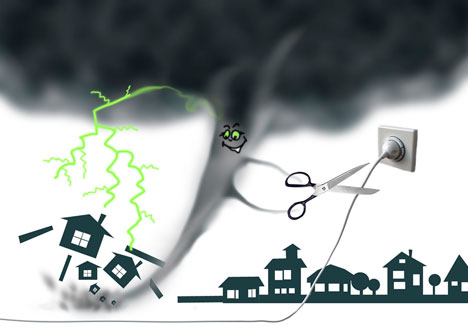

Click here to enlarge the image. Drawing by Niyaz Karim

When the water got so high the streets of lower Manhattan looked more like rivers and the downtown subway tunnels were flooded almost to the ceilings.

“So much the better,” said the city’s sanitation workers, “Sandy will drown millions of the rats that live in our tunnels and sewers.”

“What do you mean?” the Darwinists replied. “In times of flooding the strongest specimens always survive and go on to produce generations of super rats. Meanwhile, we don’t even know how to deal with the ordinary ones.”

This story strikes me as rather instructive since every new disaster to encumber New York since September 11 only gives the city more strength and determination. Gritting its teeth, it goes right on living as if nothing had happened.

How did New York respond to this latest challenge from the elements? It reopened the Metropolitan Museum of Art and announced that admission would be free. If you’re wandering around with nothing to do, if your home is flooded and you’re camping on the dry floor of friends uptown, then why not spend the day in the company of Breughel and Hals. Or of Gershwin and Beethoven whose music was being played for free at a concert hall in devastated Newark.

Of course, these are typical New York palliatives: what can’t be avoided can always be embellished. Art won’t likely console the 20,000 people who have just lost their homes, people for whom the city must find shelter ahead of a new storm (of rain mixed with snow) now headed our way.

Today it’s clear: our climate problems are serious. Accustomed to fearing unemployment and terrorists, New York has long delegated ecological threats to the Greens. Up until a week ago the Greens were considered harmless cranks, like hippies. But Hurricane Sandy woke everyone up, everyone who thought that our climate problems would work themselves out on their own. The weather has truly gone crazy, as scientists have long been warning us it would. It’s not that we didn’t believe them; it’s that we just kept putting the problem off until tomorrow. Well, now tomorrow has come and although it began yesterday, we turned out to be unprepared.

Two of the largest storms in history converged on New York this year and last.

The climate is not changing; it has already changed. And rather that waste time assigning blame, we need to learn how to live by new rules. For example, we shouldn’t build palaces, much less shacks, by the sea. All wires should be buried underground. People should own gas generators. New York harbor should be equipped with floodgates like the ones protecting Amsterdam and London. The main thing is to elect a president who will not be afraid to tell the truth or to raise taxes. Without higher taxes the United States will remain defenseless in the face of threats far greater than a few cave dwellers wanting to wipe us off the face of the earth. In that respect, nature is far more effective.

More essays of Alexander Genis:

A Russian export "better than sex" and more valuable than oil

If the lessons of Sandy are not to be in vain, politicians need to learn them off by heart. But this hurricane taught me other lessons entirely — personal and very useful ones. For an entire week I lived roughly the way Pushkin did in his small wooden house at Mikhailovskoye.

To begin with, it was dark. Like Pushkin, my wife and I were careful not to waste our candles as there were none to be bought. Our workday ended at six, when the sun went down. After that, we read Mandelstam’s poetry aloud to each other — to save paraffin — analyzing every verse. No matter how we dragged the process out, the darkness made us drowsy.

Secondly, it was cold. When the temperature dipped below freezing, neither of us had the strength to crawl out from under the down quilts that finally had come in handy. We weren’t suffering: we gave ourselves up with suspicious ease, like Oblomov, to a somnolent idleness. I whiled the days away and forgot to look at my watch.

In the third place, it was lonely. Cut off by the storm from the Manhattan we could see out the window, we decided not to venture into the city for fear of using up our gasoline. Deprived of the accustomed entertainments of New York, a city which is always ready to keep one company, we fell back on friends who lived nearby. Their electric stove wasn’t working (unlike our gas one), so they were glad to come to us and share eclectic meals consisting of all the foods in our freezers that had now defrosted. We were as happy to see them as Pushkin was to see his friend Pushchin, and met every other day until the vodka ran out.

Most frightening of all when the storm first hit was the lack of information. The television died, the phone went dead, our cell phones ran down and of course there was no Internet: it was then that I realized how right Marshall McLuhan was in predicting the Internet as an “extension of consciousness.” The web of communications surrounds us like flies, and feeds us like spiders. It turns out that a significant part of our “I”, without waiting for the end, has already crossed over into the ether. And without the Internet we feel our own sad superabundance, undiluted by other individuals.

When Sandy unplugged the “global village,” we reverted to the ordinary kind where everyone feeds on rumors and stands in endless lines for access to the only electrical outlet. Huddled by that socket, I felt as if I’d gone back to the time of America’s Founding Fathers.

This being the eve of the presidential election, everyone was talking politics — without any prompting, of their own accord, making it seem as if democracy had returned to its patriarchal roots.

Today the electricity finally came back on in our house, but I’ve decided not to turn on the television ahead of the election.

Alexander Genisis an author and journalist. He is the host of the weekly radiomagazine ‘American Hour’ (Radio Liberty) and a columnist for the independent investigative newspaper “Novaya Gazeta.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox