Revealing the mundane horrors of the Russian family

Now in her 70s, Petrushevksaya’s recent decision to become a cabaret singer has been met with some confusion and controversy. Source: ITAR-TASS

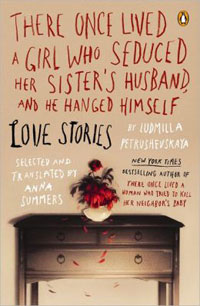

No writer captures the mundane horrors of domestic despair quite like Ludmilla Petrushevskaya. Taken together, her new collection of short stories, written between 1972 and 2008, reveals more about Russian family life in the 20th century than any non-fiction. Sober and grim, these seventeen stories eschew the supernatural twists and scary magical realism employed in her earlier, acclaimed collection, “There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby.”

|

| Book cover of "There once lived a girl who seduced her sister’s husband and he hanged himself” by Petrushevskaya, 2013. |

Yet they still read like fairy tales of a sort, small parables that occur in fetid apartments, soiled beds, dank doorways and kitchens stocked with moonshine, stale bread and bologna. When the stories end with a shred of hope, or even a numbing of the pain, the poignance can be hard to bear. Yet you keep reading. Surprising expressions of love and simple acts of loyalty stand out in relief, surrounded by the chaos of fear.

“In reality, life doesn’t stop with a wedding, heroic action, or with happy coincidence, as in films, when a certain person misses his boat (Titanic) or, as in this case, when an unmarried woman of thirty-five decides to keep the child born of a random tryst with a boy of twenty.” This first line of “Two Deities,” one of her gentler and forgiving stories, remonstrates authors who tie narratives up in a classic bow.

Petrushevskaya's story, “A Happy Ending” is almost a tongue-in-check reaction to her disgust for the grand finale. Yet the story provides the closest she allows herself to a happy ending: Polina, a long-suffering caretaker, chooses her abusive spouse, compromised by illness, over an ordered loneliness.

Another story, “Give Her to Me,” arguably ends happily. Quirky and singular, it tells the rich and entertaining story of a skinny playwright living in desperate squalor; she writes a theatrical hit with a married man who gets her pregnant and she manages not to lose her baby.

In Petrushevskaya’s world of bad choices, there is no pure, uncorrupted way to end a story. This is especially true in a world where family members disappear or decline slowly from alcoholism, and the family apartment can be perceived as a lottery ticket that could end generations of poverty and trouble.

In her stories, the (sometimes forcibly) emptied apartment can herald a new life or hasten an early death. The female characters are more nuanced than the men, and they make heroic if absurd efforts to keep the family together, or at least imagine a family that they could be the center of.

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya was born in 1938, and much of her life is one of those awful reminders of what the 20th century was like. When she was a child in Moscow, her father walked out of the apartment one day and never came back, a recurring theme in her writing. Her family was caught up in Stalin’s purges and many in her family were imprisoned and executed. She ended up in an orphanage, which maybe, in a way, was a reprieve.

At least, she has told journalists, there were regular meals and occasional entertainment, including a gypsy performance that stuck in her memory. Now in her 70s, Petrushevksaya’s recent decision to become a cabaret singer has been met with some confusion and controversy. She does not seem to care.

When she was finally reunited with her mother and sister after World War II, they lived in one room of the old apartment. And when she married at a young age, her first husband died after a long illness while still in his 30s. Petrushevskaya worked and took care of their young son alone, like so many war widows.

Each of these heartbreaking milestones finds a way into her tales in this newly translated collection, “There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband and He Hanged Himself,” published by Penguin Books and lovingly translated by Anna Summers. Each of her tales bears witness to generations of traumatized families, dispersed and disorderly, but from time to time capable of love.

The book includes Petrushevskaya’s first and most recent published stories. “Like Penelope,” a sweet story of family compassion, was published in Russia to celebrate her 70th birthday and represents her most recent work. With uncharacteristic optimism, Petrushevskaya allows for celebration of the bond between mothers and daughters.

“Mama Nina observed her daughter and wondered where this new slow grace had come from, the twinkles in her laughing dark eyes, the wave in her hair, the gorgeous dress….Of course, she had made it herself.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox