One of every two Russians has tried writing poetry, according to statistics. Today, twelve percent of Russia’s 142 million citizens write poetry, yet a poetry book’s average circulation stands at 500 copies. Source: PhotoXpress

Vladimir Mayakovsky, the most highly praised poet in the Soviet Union, was born 120 years ago this month. Adulation emerged only after his death, however, when Stalin referred to him as “the best, most talented poet of our Soviet era.” Following Stalin’s praise, society began, in Pasternak’s words, “to plant Mayakovsky like potatoes during the rule of Catherine the Great.” Students were required to learn his verses by heart and opulent official events dedicated to Mayakovsky were frequently held. The poet became a fixture of the state world.

But even that could not stop the electric charge in his poetry, which is revolutionary in the broadest sense. Mayakovsky supported revolutionary art and opposed the old world — philistines, boredom and a monotonous lifestyle.

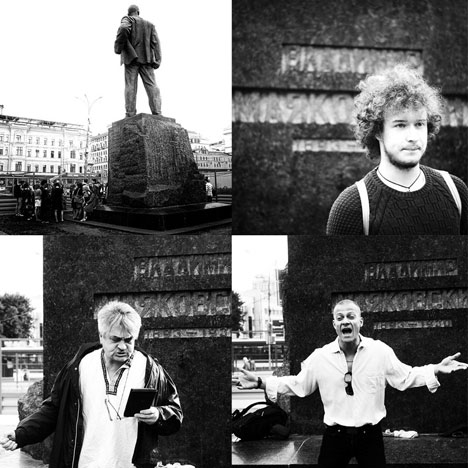

This is how the poets who convene at Mayakovsky’s monument on Moscow’s Triumph Square understand him. Four years ago, the group, calling itself K-Front (Cultural Front) began to read poetry at the monument. Matvei Krylov, one of the group’s organizers, described his friends as “poets, artists, musicians and opposition-minded students.”

He clarified: “It’s not so much about opposition to the political status quo, but rather to consumer society, to the current system of values. We do not want to consume what the official cultural institutions are offering. We do not think culture is what they show on TV, and we do not like the fact that everything is measured by money. Everything, including culture.”

A monument’s dissident history

The monument was chosen not for Mayakovsky, and not even because rallies are held on Triumph Square in defense of Article 31 of the constitution, which guarantees the freedom of assembly. There is in fact a deeper, long-established association with the year 1958, when the monument to Mayakovsky was officially opened.

Poets Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky read their works at the monument. The reading continued past the end of the official ceremony. Amateur poets and orators emerged from the crowd. In the Soviet era, this was a rebellious act. And yet the readings by Mayakovsky’s statue became a ritual.

Nowadays revolutinary poets. Source: Sergei Bobrovich

Among the participants were the well-known dissidents Yuri Galanskov and Vladimir Bukovsky, who ultimately paid for their actions; Galanskov was imprisoned, and Bukovsky was expelled from university. The poets were chased, arrested, and their “anti-social behavior” was reported to their places of study and work. In 1961, the Mayakovsky readings all but ceased.

Today, the monument draws punk enthusiasts and young women in hats with feathers; they embrace the old men reading poems about Yeltsin during perestroika on Pushkinskaya square.

Meet Semyon Bulatkin, a former war correspondent and woodcutter for ship parts from Orekhovo-Zuyevo. He started writing poetry after he retired, having never seriously done so before.

Yulia Privedennaya is from PORTOS, the Poetic Society for Development of the Theory of the Common Good. She was sent to prison for organizing an illegal militant group and started writing poetry when she was behind bars.

Natalia Botiyenko is a veteran of the war in Chechnya. While walking down the street, she saw a group of people, approached them, and began reading poetry with them. She admits that she cannot distinguish an iamb from a trochee. She believes that you have to write from the heart.

Kirill Medvedev is a poet and a translator known for his left-wing convictions.

Some found out about the event on a LiveJournal page, others were handed flyers on the street, and that was enough to get a crowd together. “I, for one, am not interested in listening to the speeches of executives or officials,” said Krylov. “I am not interested in the performances of our official stars. I am interested in hearing from people like myself.” It turns out that there are many like him.

The poems vary widely. People read Pushkin, Pastnerak, Vysotsky and, of course, their own work. Listen to this: “Consider, friend, the fate you choose for yourself at this very moment. And not even you alone, your whole generation, think of what you have your sights set on... Look around and you will see those who have surrendered, having forgotten, or wanting to forget, that their lives were spent by the latrine. They bought their burrows, gorged themselves. Their way of life is of no interest for humanity. Not a soul will grieve their death. The herd has neither a conscience nor a fatherland; only a belly grumbling evermore.”

A collection of poems by Soviet dissident poet published in English

Moscow Metro reveals avant-garde poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky

The majority of these poems are not professional, but no one here has dreams of a literary career. Incidentally, there were no major poets among the Soviet dissidents of the 1960s. The very same Galanskov’s strength was not in how he wrote, but that “...This is me / calling to truth and revolt / willing no more to serve / I break your black tethers / woven of lies.” It sounds nearly the same by the monument today.

One of every two Russians has tried writing poetry, according to statistics. Today, twelve percent of Russia’s 142 million citizens write poetry, yet a poetry book’s average circulation stands at 500 copies.

On September 1991, a farewell to the remains of poet Yuri Galanskov took place by Mayakovsky’s monument. Matvei Krylov was about three years old at the time.

What could come for this undertaking? It could die out. Authorities could disperse the poets. Alternatively, people could continue to meet and the movement could grow for the sake of promoting amateur culture; concerts, readings and lectures could be held daily. “A hundred cultural fronts will surface in Moscow,” Krylov said. “And the cultural guerrilla war will begin. That is what we want!”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox