Red Wave: How Soviet rock made it to the US

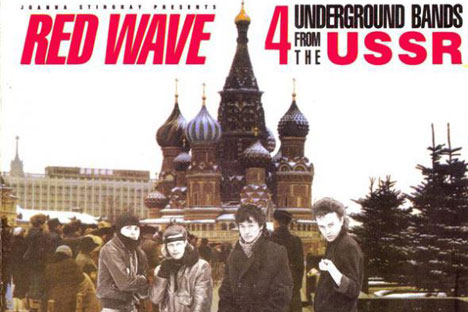

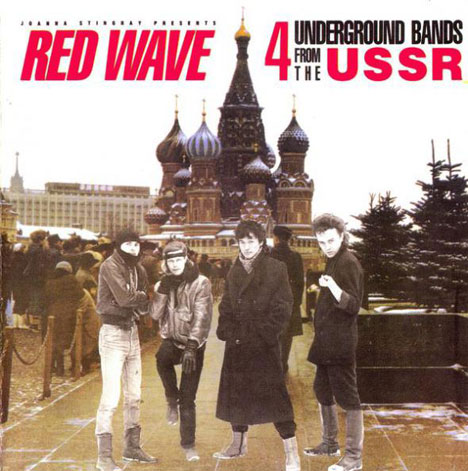

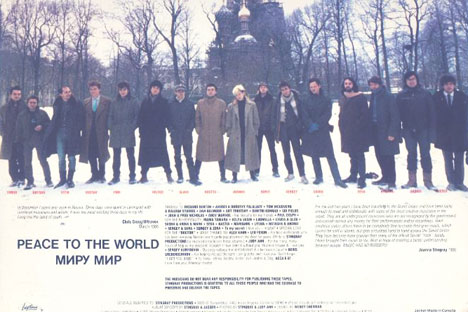

Cover of the Red Wave album. Source: Wikipedia

Editor's note: In the early 1980s, Leningrad was imbued with a musical life hidden from the rest of the world behind the Iron Curtain. Rockers experimented, protested and absorbed world culture. But they lacked even the slightest chance of official recognition and fame beyond their dedicated fan base. Reaching the West was nothing more than fantasy.

Everything changed when a young, energetic American by the name of Joanna Stingray came to Leningrad. Having visited the Leningrad Rock Club — the only place in the city which hosted officially permitted rock concerts — she saw real stars in the Russian underground performers and nonconformists.

She did everything she could to bring their music to Western listeners. It seemed like a pipe dream under such conditions, but she made it work. Music critic Alexander Kushnir tells the story in his book about world-famous, avant-garde musician Sergey Kuryokhin, who took part in the events of those years.

Below is an excerpt from Kushnir’s book, “Sergey Kuryokhin: The Crazy Mechanics of Russian Rock,” which will be published this fall.

The 25-year-old American singer Joanna Stingray played a major role in the fate of Sergei Kuryokhin and Leningrad rock.

The stepdaughter of a successful gallery owner from Los Angeles, she came to Petersburg as a tourist and unexpectedly discovered a rich rock scene there.

Soon, Joanna was going to Aquarium and Strannye Igry (Strange Games) concerts, and she became friendly with BG, Captain Kuryokhin, Tsoi, Kasparyan and the Sologub brothers.

Being a romantic, Stingray decided that before her lay a Klondike of European-caliber rock stars. She sincerely viewed Grebenshikov as a Russian David Bowie; Kinchev, as Billy Idol; and Strannye Igry, as the Petersburg Madness.

It is true that Kuryokhin did not fall into any of Joanna’s categories. After attending a Popular Mechanics concert, she realized that the Captain was something that, until then, had been mysterious and incomprehensible to her; and Stingray began to seriously think about how to pull all the local rock ‘n’ roll out of the swamp of cultural isolation.

With an energy that the Petersburg mentality was not accustomed to, she threw herself into the thicket of rock ’n’ roll events. She was unperturbed by the Soviet regime, the thousands of miles separating the Soviet Union and America, the utterly inconvertible ruble and the language barrier.

She brought along a video camera, which she began using to film dozens of interviews — from BG to Kinchev, Kuryokhin to Bashlachev. She captured house concerts and rock club festivals, and she tried to make documentary recordings.

She was arrested from time to time — like once after a New Year’s Popular Mechanics concert. “I’m an American tourist,” Joanna responded unflappably.

Source: Youtube

She was eventually released. “Since then, wherever I went, I was sometimes followed by a man with a newspaper, and sometimes a car,” Joanna recalled. “It was silly, like in an American action film.”

Despite the full-court press, Stingray continued to organize photo and filming sessions, and she then took the recorded material to California, where, sparing no efforts, she popularized Petersburg rock ’n’ roll.

“When Joanna showed up, she immediately started saying to us, ‘You’re stars! You’re super-musicians! You should be earning millions!’” Kuryokhin told me later.

“It was somehow absurd. She exerted all her energy. It was the funniest creation, purely pragmatic, with such a philosophy. Nevertheless, there were a lot of good things connected with her. Since her stepfather was a famous gallery owner, she nonchalantly hung out with Warhol, and she once brought over the famous Campbell’s soup cans. She gave them to me, Grebenshikov, Titov, Timur, Afrika, Kinchev and Tsoi… . All these cans were signed, with things like ‘To Sergei from Andy Warhol.’ Now they’re totally one of a kind…”

For a long time, the Petersburg rockers laughed at Joanna, sure that nothing concrete was likely to come of her efforts. They called her an “American tractor” and thought she would tire of hopscotching across the ocean and battling the authorities. But they were sorely mistaken.

Joanna flew the Los Angeles–Leningrad route nine times in two years. Armed with the support of David Bowie, who had become interested Aquarium’s work, Stingray signed a contract with the American recording company Big Time Records.

Joanna smuggled out contraband audio recordings of Leningrad rock groups in the guise of new cassettes, releasing them in America as a split double album called “Red Wave: 4 Underground Bands from the USSR.”

“It was very hard to produce that record,” Stingray recalled later, “because Americans were afraid of Russia; they were afraid of the Soviet Union. And when I tried to get help from people, they reacted with an uncanny fear. So I had to do practically everything myself.”

For 1986, the appearance of 15,000 vinyl “Red Wave” albums was a cultural revolution. In reality, it turned out to be the first legitimate compilation of Russian rock that people in different countries could listen to.

American record stores were filled with the sounds of Aquarium, Kino, Alisa and Strannye Igry, and Soviet cooperators began selling the collection in music kiosks.

On the day “Red Wave: 4 Underground Bands from the USSR” came out, nearly all American magazines and newspapers reacted, from Rolling Stone magazine to USA Today. The reviews were mixed, but primarily positive.

“Soviet groups will not receive a kopeck from record sales,” wrote a Newsweek reporter in the article “Red, Hot and New.” “Just personal satisfaction from the fact that their music, which was recorded on homemade spools, could cross the Soviet borders and will be listened to in the West.”

Shortly after the appearance of “Red Wave,” Joanna Stingray recorded a few records and a couple of music videos with the participation of Leningrad musicians, and she married Kino guitarist Yuri Kasparyan.

Related:

Russia's oldest record label goes digital

Exploring the roots of experimental music in Russia

At the over-the-top concert at the Pravda Palace of Culture that was dedicated to their wedding, Captain Kuryokhin played guitar and even tried to sing. He then accompanied Stingray on a series of televisionappearances, and Joanna did all she could to help the Maestro during his American tour…

But to return to the topic of “Red Wave,” it is hard to overestimate the benefit of Stingray’s public awareness efforts for the international promotion of Soviet rock at the time.

After the release of “Red Wave: 4 Underground Bands from the USSR,” trans-Atlantic journalists discovered for themselves a new musical homeland known as the “USSR.” During the summer and fall of 1986, the “Iron Curtain” between the two countries receded into the past and — o, happiness — Leningrad rock became a symbol of the imminent changes.

Soon after the Reykjavik talks between Gorbachev and Reagan, the “Red Wave” split double album was lying on the desk of the CPSU general secretary.

“Why is it that such albums come out in America, but not here?” Mikhail Sergeevich asked with interest, and he ordered the minister of culture to initiate work with young artists.

For the first time since the Tbilisi festival in 1980, the green light was given to rock groups. The all-Union Rock Panorama ‘86 festival was held Luzhniki, and, shortly thereafter, the recording of the festival was released on vinyl by Melodiya.

In the fall of 1986, the Grebenshikov crew played six official concerts in the Oktyabrsky Concert Hall. The first “official” Aquarium record, issued by Melodiya, was sold throughout the country in massive release.

After Aquarium appeared on “Musical Ring” — a top national program on Central Television — it became clear that there was no turning back.

Friends recall that, in the mid-1980s, Kuryokhin was one of the first to truly believe in Gorbachev and the idea of perestroika. He said that positive changes would soon occur in the Soviet Union.

And while the Moscow and Petersburg bohemians tried to guess whether or not they would be allowed to go abroad, the Captain was already telling musicians about future performances of the Popular Mechanics in Europe.

“At the very beginning of perestroika, I had the feeling that now art would finally be completely liberated,” the Captain said a few years later.

“And I believed that art would really take off, and that people who were traditionally labeled ‘artistic’ ought to do some simply unbelievable things.”

Alexander Kushnir is a music critic and author of the books “Golden Underground: A Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock Samizdat,” “100 Reel-to-Reel Albums of Soviet Rock: 1977–1991,” and “Headliners.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox