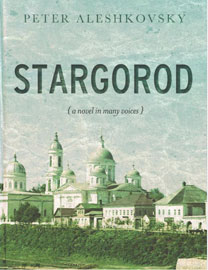

'Stargorod': Fractured fables in the style of James Joyce

|

| Source: amazon.com |

In the middle of Peter Aleshkovsky’s “Stargorod” is a story about the town archivist. A fortress of a man in a worsted coat and thick glasses, Pavel Ogorodnikov sorts through ancient files to unearth the old town’s stories and complaints: “the usual fervent Russian begging, laced with despair and abandonment. And all of it local, Stargorodian.”

At the novel’s heart there is a powerful sense of a place and the people who live in it, slowly building into a broader picture. Aleshkovsky, who has been a historian and archaeologist, explains that “Stargorod” is “a place that is by definition on the margins … of the known world” and yet preserves the “nation’s metaphysical essence.”

Three shortlists for the annual Russian Booker Prize have included works by Aleshkovsky. His early hit “Stargorod” is combined here with the recent “Institute of Dreams” into one volume; they were originally published twenty years apart, in 1990 and 2010. Versatile translations, by Nina Shevchuk-Murray, make both novels available this year for English readers.

Although Aleshkovsky claims the two parts of “Stargorod” are “a single expansive story, woven by a great multitude of voices,” the 2010 section has a different feel. Instead of the perestroika-era grimness with hints of magic realism and folk motifs, there are pacey, modern fables, full of flying ballerinas, enchanted chimpanzees, poisoned pickles and ghostly princes.

Aleshkovsky compares the “Truth of Life” with the “truth of fairy tales” and borrows from an international legion of supernaturalists, from C.S. Lewis to Hans Christian Andersen. One story’s heroine, Katya Puck, walks through a Narnia-style wardrobe-portal onto a Sakhalin beach and later turns into a mermaid.

Inspired by Gogol’s “Mirgorod,” a collection of short stories published in 1835, Aleshkovsky’s title replaces Gogol’s “world” (mir) with “old” (stary). The idea of a set of stories, chronicling the life of an old town (Stargorod) is borrowed – as he acknowledges in his preface – directly from Nikolai Leskov. There are echoes of both writers in Aleshkovsky’s satirical storytelling, but he also reflects a contemporary era of “bleached denim,” fast cars and “sexy T shirts.”

For a non-Russian, “Stargorod {a novel in many voices}” can be problematic. Firstly, despite the subtitle, it is not a novel, but a collection of short stories, linked by setting, in the style of James Joyce’s “Dubliners” or Isaac Babels’ “Odessa Tales.”

Despite recurring themes and characters, those expecting a continuous plot will be disappointed. Russian book lovers may be more comfortable with this format; several celebrated “novels,” from Lermontov’s “Hero of Our Time” to Zakhar Prilepin’s “Sin,” are basically groups of interlinked tales.

Another obstacle is the density of allusions and references. Borrowings from Gogol or Leskov are the more obvious among the author’s self-confessed “inside jokes, shameless quotations and stolen plots.” The joy of recognition for a knowledgeable reader is matched by a growing sense of bafflement for those who feel they are missing something.

The book begins and ends with stories about writers. The late-Soviet-era writer Pishchutin, dressed in his navy blue velvet suit, made from the local theater’s discarded curtain, is a suitably wistful opening figure. With his gold-tipped pen, he longs to write satire, but finds himself pitying his subjects so that “tragedy comes instead of laughter.” The final story, told by a first person narrator, describes the “happy madness” of writing a story a week for a year with a magic pencil.

“Stargorod” contains a multitude of individual voices, weaving a complex tapestry that is more than the sum of its parts. Adding to the sense of live speech, the stories often seem to start in the middle an ongoing conversation and finish abruptly. Enjoyment depends on the leisure and willingness to hear these voices, just as Aleshkovsky did: “I listened to the human choir around me and stole from it everything that was worth stealing.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox