Exploring the Russian America that almost was

The show about Rezanov’s life that so affected Matthews, “Juno and Avos,” refers to the names of the ships Rezanov sailed to America. Source: ITAR-TASS

A daring and cynical explorer

Since he was a teenager, Owen Matthews has been obsessed with the flamboyant adventurer Nikolai Rezanov. Though Rezanov’s vision of a Russian America at the dawn of the 19th century is virtually unknown to Americans, “every Russian knows him as this romantic lover,” said Matthews, a journalist and former Newsweek bureau chief in Moscow.

The young Matthews knew by heart the hugely popular Russian rock opera “Juno and Avos.” The story is inspired by the love affair between Rezanov and Conchita Arguello, the teenage daughter of the local Spanish governor in California.

Matthews, born in London to a Russian mother and a British father, considers Russian his first language. “If languages have a color, Russian was the hot pink of my mother’s ’70s dresses, the warm red of an old Uzbek teapot,” Matthews has written. English was the territory of his father: “the muted green of his study carpet, the faded brown of his tweed jackets.”

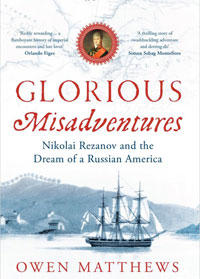

In researching Rezanov for his new book, “Glorious Misadventures, Nikolai Rezanov and the Dream of a Russian America” (Bloomsbury), Matthews discovered a more complicated, and strategically ambitious character than the tragic hero of Russian opera. (The book, published in English in December 2013, is about to appear in Russian).

Owen Matthews. Source: Philippe Matsas

“The real Rezanov is much more interesting,” Matthews said of the aristocrat cum explorer. “He was a son-of-a-bitch, really arrogant, and toward the end, mentally unstable. He was cynical and mercantile. He saw the world ‘how it might be, not as it was.’ …He was not a good man, but a great man.”

“Let’s put it this way,” Matthews said in an interview with RBTH. “Conchita was not the first teenage heiress in Rezanov’s life.” Matthews is referring to Rezanov’s politically important first marriage to 14-year-old Anna Shelikhova, the teenage daughter of the most important fur trader in Russia, known as the merchant King of Siberia.

Closer to Rezanov’s own age was Anna’s mother, Natalia Shelikhova. Upon her own husband’s death, she would manage to wrest control of his fortune and become one of Russia’s first female oligarchs. Natalia is one of the most intriguing – and certainly among the most sane – characters in Matthew’s thrilling book.

|

'Glorious Misadventures' by Owen Matthews, 2013. Source: iTunews |

“Glorious Misadventures” takes readers back to that “long-forgotten age when the Russians and the Spanish were the masters of the wilderness between Alaska and California,” commented Orlando Figes, author of “Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia.”

Love story turned rock opera

The show about Rezanov’s life that so affected Matthews, “Juno and Avos,” refers to the names of the ships Rezanov sailed to America. The rock opera premiered in 1981 at the Theater of Lenin’s Communist Youth League or “Len-Kom” and still plays to packed houses in Russia today.

“In the mid-1980s, “Juno and Avos” fans would queue for days for tickets for the performances, which occurred, with characteristic Soviet indifference to the laws of supply and demand, only once a fortnight,” Matthews wrote in the introduction to “Glorious Misadventures.”

But what impressed Matthews most about this eccentric rock opera was that it was largely true, and little known: “Russia really did once have an American empire. By 1812 the border of the Tsar’s dominions was on what is today called the Russian River, an hour’s drive north of San Francisco along Route 1. Rezanov spent much of his life passionately advocating the idea that America’s west coast could be a province of Russia, and the Pacific a Russian sea. This was no mad pipe dream, but a very real possibility.”

In the next 300 or so pages, Matthews tells a swashbuckling, epic, and sometimes brutal story—about the Russian America that quite nearly happened at a time when huge swathes of the “new world” were being bought and sold by the monarchs of Europe.

The Economist called the book “an exemplary account of adventures that could have changed the world,” while the Financial Times said the story was “like a cross between Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ and Gogol’s ‘The Government Inspector.’”

Matthews research and travel makes Siberia, Alaska and California come alive with vivid detail and a sense of the enormity of the challenges facing these frontiersmen and women.

“It was very powerful to finally see Fort Ross in California,” Matthews said, adding “I felt this great swell of pride….Suddenly you see this Russian church and Russian stockade and a number of crosses, it’s very moving and evocative. On a human level, it’s also hard not to feel sorry for Conchita. I did a sort of cheesy thing and picked a rose next to Conchita’s grave [in California] and saved it. When I arrived in Krasnoyarsk, I placed the rose on Rezanov’s grave.”

|

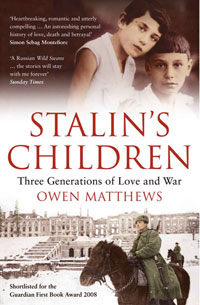

'Stalin's Children' by Owen Matthews, 2008. Source: iTunes |

Matthew’s first book, “Stalin’s Children: Three Generations of Love, War and Survival,” is a memoir centered on the heartbreaking love story of his parents. Mervyn Matthews, Owen’s father, arrived in Moscow in the early 1960s for a graduate program at Moscow State University. He met Lyudmila, the daughter of a Red Army officer who was purged during Stalin’s Terror. The couple fell in love and married, and just as hastily, Matthews was deported.

When they were finally reunited several years later, Mervyn Matthews had compromised his own academic tenure to win his beloved’s release. His career was in tatters. Lyudmila had her own demons; she was raised in an orphanage as her own mother, Owen’s grandmother, languished in a Soviet prison. Matthews tells the story lovingly, and it is at times hard to bear. The 2008 book was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award and was a Book of the Year in the Sunday Times and Sunday Telegraph.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox