Tolstoy on Twitter: A novel approach to boost sales

Pushkin in the sunglasses. The poster says: 'Sunglasses for bright people'. Source: Press Photo

Alexander Pushkin is the most famous Russian poet. His works are read in Russia and abroad, and have been dramatised in theatres around the world and adapted for cinema.

Pushkin is a major symbol of Russian culture, behind only the matryoshka doll, the bear and the balalaika by a small margin in terms of popularity.

Many people have tried to make money from his name. The first large company to use the Pushkin brand was founded in 1899, to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the poet’s birth. That year, anniversary gifts were so popular that they were mass produced: vodka, cigarettes and sweets named after Alexander Pushkin sold like hotcakes.

Vodka and cigarettes gets Pushikin face. Source: Press Photo

Today, football shirts, sunglasses, prime real estate and building materials all advertise Pushkin. The poet’s name has also been pressed into service by such brands as Nescafé, Coca-Cola and Mars. His portrait can be found on packaging and on café signs even outside Russia’s borders.

Alexey Gvintovkin, managing director of the BrandHouse Group says: “Using Pushkin’s image and his works is a win-win option. If we are aiming at overseas markets, this approach lends a product a certain charm, illustrates traditions and the distinctive character of the mysterious Russian soul.”

Literary air fresheners

As for literary classics, one of the boldest marketing moves in recent years was an advertising campaign created by the Voskhod agency, which won a bronze Cannes Lions prize in 2011. Voskhod produced a series of air fresheners with extracts from literary classics printed on them for the 100 Tisach Knig (100,000 books) chain of bookstores.

The agency decided most people read in the bathroom, so why not print literary works on air fresheners? The literary air fresheners were distributed around shopping, entertainment and business centres, restaurants and bars.

This unusual approach increased the footfall at 100 Tisach Knig bookstores by 23pc. Russia’s largest brewer, Baltika, ran a television campaign in 2011 that used Mikhail Lermontov’s poetry. The campaign, by the agency Leo Burnett Moscow, was Baltika’s first image-led campaign in 10 years and covered the entire range of Baltika beers.

According to Sergey Denisov, who worked on the project, Leo Burnett Moscow relaunched the Baltika brand. Research at that time showed that the brewing giant had become an unfashionable and even boring brand in the eyes of consumers, with a variety of products but no cohesive concept across the range.

“We decided to rectify the situation and Lermontov’s poetry served as the basis for an off-text advertisement,” explains Mr Denisov. Extracts from works by Russia’s second most famous poet after Pushkin served to remind audiences of their common roots and cultural heritage.

The impact of the Lermontov campaign on Leo Burnett Moscow’s performance is uncertain but the company’s earnings increased by 13.2pc, according to the accounts for 2011.

Writers are trusted

In an internet advertising video entitled, “How would the world look if the internet had been around for thousands of years?” Google imagined Leo Tolstoy on Twitter. The author, known for his commitment to long sentences and detailed descriptions over a number of pages, is shown trying to post an update on Twitter.

Leo Tolstoy: '140 characters is a highly frustrating restriction, and furthermore one that causes me offence.' Source: Twitter

This clever marketing move attracted public attention and around 300,000 users viewed the clip. “The top echelon of writers is a cultural code. If we use their image in an advertisement or quote their works, it means we are aiming at a specific target audience: one that is relatively wide, with average education and income,” says Yekaterina Alekseyeva, head of the department of classical prose and poetry at publishing house Eksmo.

According to Ms Alekseyeva, there is a level of trust in the great authors that provides the required association with the product being advertised: Tolstoy does not give bad advice.

Authors on social networks

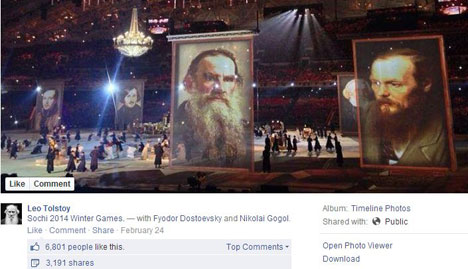

In 2010, Affekt put together an unusual promotional campaign for the Book Market book festival. Accounts were generated on Facebook in the names of Tolstoy, Pushkin, Gogol and Dostoyevsky. Their status updates provided pseudo-classical commentary on current events in Russia and abroad, and they answered users’ questions and corresponded between themselves.

As a result, more than 1,000 users became “friends” with the virtual authors in just 10 days and more than 10,000 visited their pages. But Facebook’s administrators declared the Facebook accounts a violation of its rules and deleted them.

But neither the advertising agency nor the organisers of the festival made a loss. “An author’s copyright remains valid for 70 years after his or her death. They are then made available to the public and there is no need to ask permission to use them,” explains Anna Topornina, a lawyer at Yukov and Partners.

The descendants of great writers do not receive any royalties. Apart from that, they have no influence over the context in which a body of work is used – as was the case with Lermontov’s poetry appearing on a beer advertisement.

This may seem unfair, since the images of respected authors could be used in inappropriate ways. But in practice the esteem in which great writers are held makes advertisers nervous of doing anything to incur the wrath of their fans.

Online rivals

Tolstoy might have lost one Facebook account, but he lives on in the social network in a page devoted to him by the US publisher of his works, Vintage Books. More than 735,000 people have “liked” Leo Tolstoy’s Facebook page, which is filled with quotations from his works and references to articles about the author.

Leo Tolstoy cheked-in with Russian writers at the Sochi Olympic Games. Source: Facebook

He seems to be twice as popular as Chekhov, whose own page, apparently set up by the publisher Random House, has been “liked” by 336,000 people since he “joined’’ Facebook in 2012.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox