The final days of Russian writers: Nikolai Gogol and Anton Chekhov

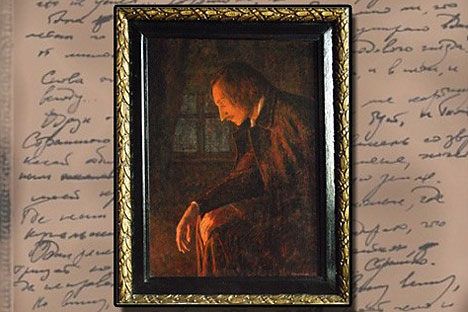

Nikolai Gogol burning the second volume of 'Dead Souls.' Source: Press image

For whom the handbell tolls

February, 1852. The writer Nikolai Gogol lies dying. He strains to pull the half dozen leeches off his nose, but his hands are too firmly tied to the bed. Meanwhile, the quack doctors treating him prepare another boiling hot bath and send for more pitchers of ice water to dunk over his head. It is a sad end for a true great of Russian literature, whose success and fame could not save him from a sense of failure and a morbid fear of death that plagued his last days.

Gogol was already a celebrity when he returned to Russia in 1848 after more than 10 years in Europe. He had gained popular success with works such as “The Government Inspector,” “The Nose,” “The Overcoat” and the first part of “Dead Souls.” This was a man who wrote the first works of Russian surrealism and the grotesque and was so important to the future development of Russian literature that there is a quote, which some attribute to Dostoyevsky and others to Turgenev, stating, “We all came out of Gogol’s overcoat.”

Despite his success, Gogol had unfulfilled literary ambitions. He was deeply drawn to the land of the great Dante and the literary legacy of the Renaissance, and tried to create his own “Divine Comedy.” Gogol was frustrated that he had only managed to recreate “Inferno” in the first part of “Dead Souls,” so he decided to write his own “Purgatorio” and “Paradiso” in the second volume. He was determined that the continuation of his “poem” would present characters with virtue and integrity – a moral example for his Russian audience. Up till then, Gogol’s readership had largely seen his work as outrageous comedies, apparently missing the deep pathos of the human condition that lay behind the odd humor and absurd characters.

…By the autumn of 1851, Gogol had settled in Moscow at a house owned by his friend Count Alexander Tolstoy. He had a close circle of acquaintances, including the philosopher Aleksei Khomyakov and the poet Nikolai Yazykov. Khomyakov was married to Yazykov’s sister Catherine, a smart, kind and caring woman. However, Gogol did not get long to enjoy his close-knit friendship group before tragedy struck: Catherine died in January, 1852, barely three days after getting sick with typhus. She was just 35.

Gogol was devastated by Catherine’s death. Gripped by a fear of his own mortality, he sank into a deep depression and turned to religion for salvation. His spiritual adviser was an ultra-orthodox priest called Father Matvei Konstantinovsky, who viewed writing as the devil’s work. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, Gogol declared the second volume of “Dead Souls” a failure and burned it, along with many other manuscripts. Visitors to Moscow can go to his house on Nikitsky Boulevard and imagine the frenzied writer carrying out this destructive act there.

A month later, Gogol decided to fast for Maslenitsa, a week-long feast before Orthodox Lent where people usually gorge themselves before giving up dairy products. It was a step too far for a man who was borderline obsessed with food, and he couldn’t hold out. When he broke the fast his physical and mental state deteriorated so severely that his doctors saw no choice but to prescribe leeches and boiling baths in an attempt to snap him out of it. The treatment was a stunning failure, and the writer died on February 21, 1852, at the age of 42.

Legend has it that Gogol was prone to spells of lethargy and was paranoid that he would be mistaken for dead during one of these spells and buried alive. According to rumor, he wanted his coffin to have an air hole and a rope leading to a handbell at the surface so he could ring for help if he woke up in a grave. There was no such final twist to Gogol’s story, however, and he was buried peacefully at the Danilov Monastery cemetery.

Champagne and oysters

Anton Chekhov’s death on July 2, 1904, has become the stuff of literary folklore. The famous writer was staying at the spa town of Badenweiler, Germany, where he was being treated for tuberculosis by Dr. Schwohrer, a specialist in lung disease. At two o’clock that morning, Chekhov – who was a trained physician himself – asked his wife, Olga Knipper, to summon the doctor for his final moments. She went to the two Russian students in the adjoining room and asked them to fetch the doctor right away because her husband was delirious.

As soon as Schwohrer entered, Chekhov declared, “Ich sterbe” – “I’m dying.” The doctor administered him an injection of camphor to try to accelerate his pulse, but it had no effect, so he called for a bottle of oxygen. “What for?” Chekhov asked. “It’s pointless. By the time they bring it, I’ll be dead.” Schwohrer realized that his patient really was on the brink of death and telephoned for a bottle of the best champagne. “How many glasses?” the attendant asked. “Three glasses,” the doctor shouted. “And hurry, do you hear?”

Olga poured her husband a glass of the finest Moet, which he took with the remark, “It’s been a long time since I drank champagne.” He finished his drink, lay down on his side and stopped breathing. “It’s over,” Schwohrer said. Olga would recall that moment in her memoirs, writing, “There were no human voices, no everyday sounds. There was only beauty, peace and the grandeur of death.”

As Chekhov had died abroad, his body needed to be taken to Moscow. To protect it from the summer heat, his coffin was loaded onto a freight train for transporting oysters. What might have seemed like a neat solution bemused some friends and relatives waiting in Moscow and offended others. Then, when a military band waiting at the station struck up a funeral march, the gathered mourners assumed that the authorities had decided to pay homage to the great playwright. After all, his last play, “The Cherry Orchard,” had been a stunning success at the Moscow Art Theatre just a few months earlier. Another ripple of shock and surprise spread through the crowd when they realized that the military music was actually for General Keller, whose coffin had arrived on another train, following his death in Manchuria.

Although some were outraged at the events surrounding the funeral, Chekhov himself would surely have appreciated his tragicomic sendoff. It was a fitting end for someone whose literature is filled with the irony lurking around every corner in our lives.

Read more about the final days of Russian writers:

Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov

Alexander Blok and Nikolai Gumilev

Sergey Esenin and Vladimir Mayakovsky

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox