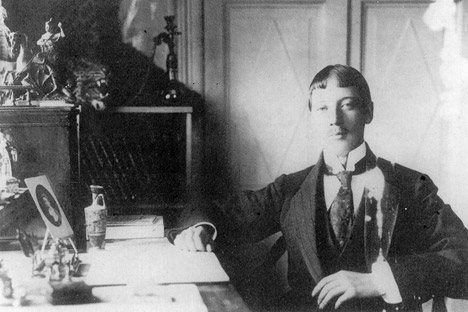

Alexander Blok. Source: Nappelbaum / RIA Novosti

Suffocated by the revolution

Alexander Blok supported the revolution and actively worked for the new government, heading the Petrograd branch of the All-Russian Union of Poets from 1919 until his death. It must have been even more of a blow, then, when he was arrested by the Cheka – the first Soviet state security organization – on suspicion of plotting against the Bolsheviks. This was just one of a series of personal and professional misfortunes that scarred the poet’s last years. His poems “The Twelve” and “The Scythians” were panned by most critics, and he drifted apart from his wife, actress Lyubov Dmitrievna, the daughter of the great scientist Dimitri Mendeleev.

In the final years of his life, Blok became increasingly reliant on alcohol and brothels for comfort and lost faith in the revolution, realizing that the new authorities were only seeking to build a new bureaucratic apparatus of oppression. “I'm suffocating, suffocating, suffocating!” he complained in one of his letters. “We’re suffocating, we will all suffocate.”

In February 1921, the 84th anniversary of Alexander Pushkin’s death was approaching. Blok, who was widely regarded as one of the greatest living Russian poets of his time, was invited to give a memorial speech on this occasion. “Peace and freedom were taken away,” Blok declared. “Life had lost its meaning … It was not d’Anthes’s bullet that killed Pushkin. It was the lack of air.” Many listeners interpreted these words as a reflection on Blok’s own life, which sounded as if it was drawing to a close.

The poet gave a couple of recitals in the few months before he died, first in Petrograd and then in Moscow. These readings resembled a kind of rehearsal for Blok’s own funeral wake. Mayakovsky remembered: “He quietly and sadly read lines about gypsy singing, about love, about the beautiful lady – there was no way forward. Only death.”

Blok stopped writing poems long before his death. He became prone to outbursts of anger, which alternated with fits of depression. Sometimes he would talk nonsense or hallucinate that devils and ghosts had come into his room. His condition became so frightening for his wife and friends that they knew they had to act quickly to save the poet.

Maxim Gorky, who used his closeness to Lenin to help many writers in difficult circumstances, asked the leader to let Blok travel to Finland for medical treatment. Lenin refused: after the revolution, Blok had sympathized with the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which had eventually become an enemy of the Bolsheviks. Gorky was incensed and declared that the Bolshevik leader had become a “thinking guillotine.”

By the time he convinced Lenin to give his consent, it was too late – Blok was already too weak to leave his home. In a letter to his friend, Blok called death “abroad, where everyone goes without preliminary permission from the authorities.” It was a hot August 7, 1921 when the poet finally died, succumbing to acute endocarditis.

Blok’s apartment on the second floor of 57 Ofitserskaya was filled with people for three days, as hundreds of famous and anonymous well-wishers came to lay flowers at the poet’s deathbed.

On August 10, the day of the funeral, the mourning cortege traveled four miles on foot to the cemetery. The Mariinsky Theatre choir sang Rachmaninov’s mass and the Tchaikovsky liturgy during the final service. A simple wooden cross was erected on the tomb. The writer Evgeniy Zamiatin described the farewell: “And finally – underneath the sun, along the narrow, tree-lined paths – we carry that foreign, heavy something, which is left of Blok. And silently – in the same way that Blok had been silent in these years – silently the earth swallows Blok up.”

In an article dedicated to the poet, the Russian composer Arthur Lourié expressed the general feeling of the intelligentsia when he wrote, “The Russian Revolution ended with the death of Alexander Blok.”

The last conquistador

Nikolai Gumilev. Source: open sources

It was during Blok’s funeral itself that the poet Anna Akhmatova received the news that her former husband, the poet Nikolai Gumilev, had been arrested by the Cheka a week before, on August 3.

Gumilev was suspected of having participated in the so-called Tagantsev conspiracy. In 1921, the St. Petersburg professor Vladimir Tagantsev publicly declared that he would be willing to participate in any potential uprising against the Soviet government. Tagantsev’s organization did indeed plot such an uprising, but Gumilev wasn’t involved in its planning. Apparently, he just knew about the conspiracy and stored some of the printed proclamations at his home. His crime was not handing over this information to the authorities.

The Bolsheviks also had other reasons to hunt down Gumilev. It was known that Nikolai had been a monarchist, an officer of the Tsarist army, and one of the intellectuals that hadn’t supported the revolution. On the other hand, it was also known that he wasn’t particularly interested in politics.

Nikolai Gumilev was a committed bon viveur, womanizer and fully-fledged adventurer. He had been drawn to images of European knights and brave conquistadors since childhood, and wanted to emulate these romantic and exotic heroes in his own life. After studying in Sorbonna, he traveled extensively in Africa on the commission of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In Africa, Nikolai hunted lions and leopards in the jungle, met prominent Africans – including the future Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie – and wrote poetry.

When the First World War started, he enlisted voluntarily. He received the Order of St. George twice, which was only awarded for bravery in battle. Gumilev could have easily stayed at the headquarters or in St. Petersburg – as many other writers did at the time – but he fought on the front lines. Perhaps it was a way for him to overcome the spells of fear that he had suffered since his youth.

In spring 1918 Gumilev was in London. When asked whether he wanted go to hunting in Africa again, continue his military service, or return to Russia, which was ablaze with revolution, the poet answered: “I have been in battle enough, I was in Africa three times, but I have never seen the Bolsheviks. I’m going to Russia – I don’t think it could be more dangerous than hunting lions.” He couldn’t have been more wrong.

Unlike Blok, Gumilev was not silenced by the revolution. He went on writing because he believed in the positive influence of literature on mankind. Gumilev had extensive creative plans and began working at Gorky’s new publishing house. In this period he translated classics of world literature, gave lectures and recitals, and did anything to support his family in the starving Petrograd. He also held workshops for young poets that wanted to learn the poetic trade. And then, out of the blue, he was arrested.

From the beginning of his imprisonment, Gumilev believed that he would be released, which explains the tone of the letter he wrote to his second wife, Anna Engelgardt: “Don’t worry about me. I’m well, writing verses and playing chess.” However, on the wall of his Petrograd cell he wrote, “God, forgive my sins as I embark on my last journey. Gumilev.” His interrogator, a man named Yakobson, was highly educated and cunning. He praised Gumilev, recited his poetry by heart and discussed European philosophy. Then, after the fourth interrogation he sentenced the poet to execution by firing squad.

When Gumilev was arrested, a number of his friends and fellow writers – including Gorky – signed a petition asking the Cheka to pardon him. The reprieve reached Petrograd 10 days after Nikolai Gumilev had been executed on the morning of August 25, 1921.

Years before his execution, Gumilev wrote, “I won’t die in a bed, with a notary and a doctor standing by, but in some wild gorge, covered in thick ivy.” These words turned to be a prophetic: the exact place and circumstances of his execution remain unknown to the present day.

Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov

Nikolai Gogol and Anton Chekhov

Sergey Esenin and Vladimir Mayakovsky

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox