The final days of Russian writers: Sergey Esenin and Vladimir Mayakovsky

Hooligan, poet, murder victim?

In the months leading up to Esenin's death the Soviet authorities had become increasingly concerned about the poet’s drunken debauchery.

TASSOn Dec. 25, 1925, Sergei Esenin checked in to the Angleterre Hotel in St. Petersburg. He wouldn’t leave it alive.

The writer was 30 and a disillusioned man, tired of life, women, poetry and his friends. He had become the enfant terrible of Bolshevik society: disorderly and rebellious but also talented, loved by the public, and loyal to the new authorities. Yet he had also become increasingly provocative in recent years; his 1921 work “Confessions of a Hooligan” had revealed another side to his personality: anguished and vulgar. His drinking was getting out of control, and the authorities were beginning to notice.

With his blonde, curly hair and light-colored eyes, Esenin looked like a typical big screen heartthrob – although his rude manners were at odds with his homely, boy next door looks. Despite this, the writer was an undoubted ladies man who had three failed marriages under his belt by the time he died. His most famous was with the contemporary American dancer Isadora Duncan – 17 years his senior at the age of 45.

After their marriage, they set off on a year-long trip to Europe and the United States. To the delight of the international press, there was no shortage of fighting in public and violent outbursts by Esenin, who was always drunk. He found nothing of interest in the West – except the foxtrot – and no one seemed interested in his work there anyway. The couple split when they returned to Russia.

In 1925, Esenin was married to one of Tolstoy’s granddaughters, Sophia, who forced him to check himself into hospital. Unfortunately, the therapy had no effect, and there seemed to be no hope for his depression and alcoholism. When he left the hospital, the writer withdrew all the money from his account and went on a drinking spree.

Esenin ended up at the Angleterre Hotel after being forcibly removed from the writers’ bar, where he knocked over furniture, smashed glasses on the floor, and abused his fellow drinkers with claims that they were“arrivistes” and “mediocre.” He spent two days drinking vodka in his hotel room, before slashing his wrists on Dec. 27 and writing his last poem with his own blood: “Goodbye, my friend … / There's nothing new in dying now / Though living is no newer.” The following morning, Esenin was found hanging from the heating pipes on the ceiling.

What seems like an open and shut case of suicide may not be so simple. In the months leading up to his death the Soviet authorities had become increasingly concerned about the poet’s drunken debauchery. Criminal charges were brought against him and his friends because of their numerous brawls, and the Bolsheviks feared that Esenin could start to denounce the new government. Apparently there was even discussion of putting the poet under continual surveillance. This has led to unproven speculation that Esenin was assassinated by the secret police – a theory that is still hotly contested.

Esenin was so famous that his death triggered a wave of copycat suicides. The communist authorities, who viewed Esenin’s poetry with suspicion for its individualism and “hooliganism,” reacted strongly, and his books were banned for many years after his death. Students who read his poems could be expelled from university, and distributing manuscript copies of his poems was punished with jail time.

Esenin’s spirit could not be repressed, however, and he remains a poet of the people to this day: tragic, flawed, with a romantic style to match his image.

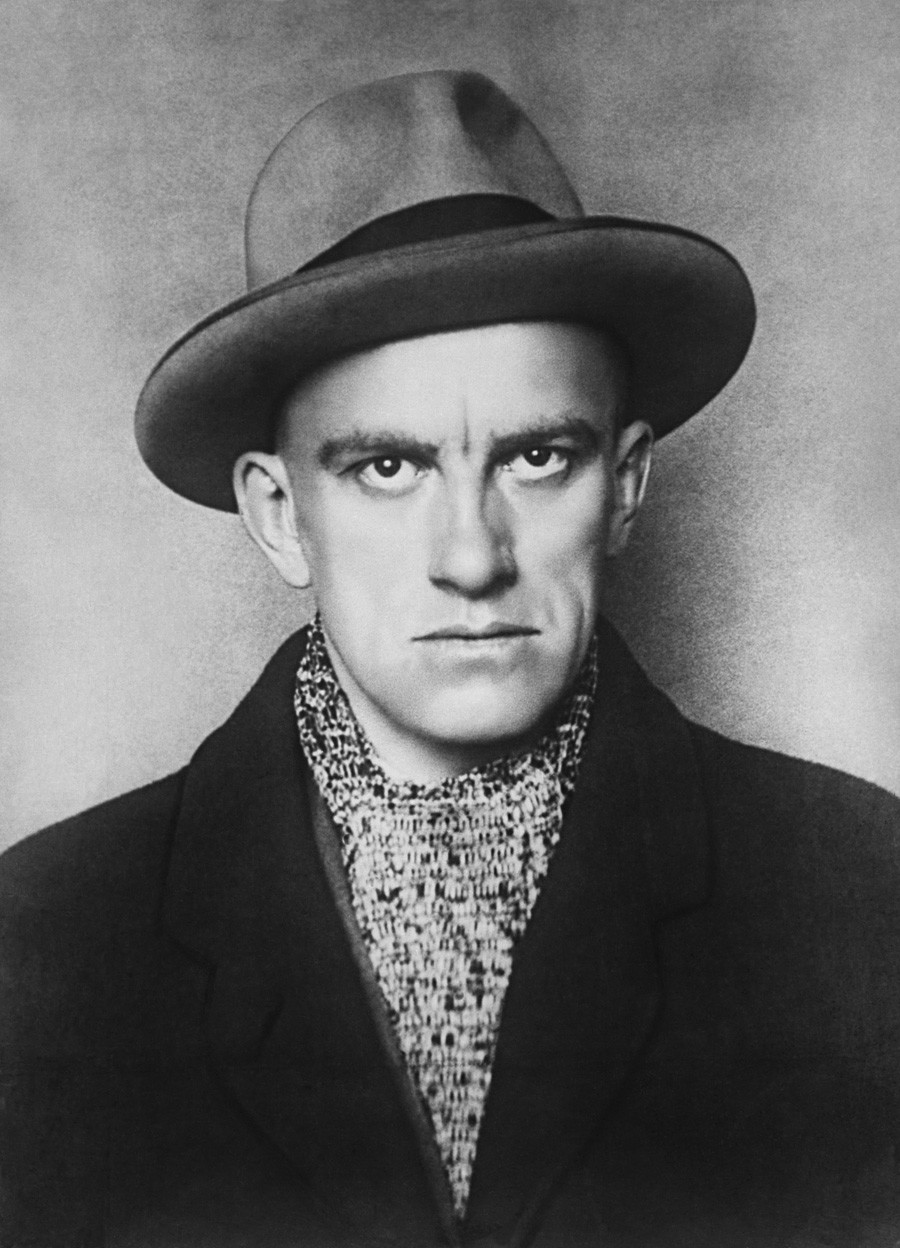

The main revolutionary poet dies

It is not exactly clear why Mayakovsky took his own life.

TASSVladimir Mayakovsky was deeply affected by Esenin’s suicide, taking it as a betrayal of communism. Mayakovsky felt morally obligated to write a requiem poem, where he took Esenin’s last lines and gave them a different meaning, as if reproaching the late poet for the decision to take his own life: “It’s not difficult to die. / To make life / Is more difficult by far.” Paradoxically, Mayakovsky would commit suicide less than five years later, on April 14, 1930. He would be just 37.

Mayakovsky was the revolution’s foremost poet and poured his heart and soul into the Bolshevik cause. As critic Viktor Shklovsky wrote, “Mayakovsky entered the revolution as he would enter his own house.” He took socialism into the factories, his poems were constantly published in newspapers and magazines, he wrote screenplays, and even worked as an actor.

Although Mayakovsky was very successful, he suffered a great deal of frustration in his private life. It was in his early twenties when he fell in love with Lilya, the wife of his publisher, Osip Brik, and went on to dedicate some of his most beautiful poetry to her – including “A Cloud in Trousers.” In 1925, Mayakovsky traveled to Europe, Mexico, Cuba and the United States. While in the U.S., he fell in love with the actress and model Elly Jones – originally Elizaveta Petrovna Zibert – but they kept the affair a secret: it wasn’t fitting for a Soviet poet to get involved with an immigrant. The pair had a child, Patricia Thompson, who now goes by her Russian name, Yelena Vladimirovna Mayakovskaya.

Days before he shot himself, the poet left a letter addressed to his mother, sisters and friends. It was written in the tone of lighthearted irony that was so typical of his character: “Do not blame anyone, and please do not gossip. The deceased terribly disliked that sort of thing.” The letter concluded: “And so they say – / ‘the incident dissolved’ / the love boat smashed up / on the dreary routine. / I'm through with life / and [we] should absolve / from mutual hurts, afflictions and spleen. / Good luck.”

A widely accepted version of Mayakovsky’s death says he shot himself after a showdown with the actress Veronika Polonskaya, who he had been in a brief but very stormy relationship with. Polonskaya was in love with the poet but unwilling to leave her husband. Moments after walking out of Mayakovsky’s apartment, Veronika heard a gunshot. She hurried back inside, only to find a crimson spot spreading across his white shirt. The ambulance arrived minutes too late to save Mayakovsky, who died of a gunshot wound to the chest.

It is not exactly clear why Mayakovsky took his own life, but it is likely that his failed love affair was just the final straw in a long sequence of problems. By the end of 1920s, Mayakovsky had become disappointed with the course of Soviet politics. He wrote satirical plays mocking narrow-minded contemporary Soviet citizens and bureaucrats, but they were badly received – the critics of the day were too loyal to the party. Mayakovsky’s personal art exhibition was disregarded by writers and literary officials alike, and he was denied permission to leave the country – a real blow for someone who enjoyed traveling to Europe. Finally, days before he died, the writer was booed and insulted by students at the University of Moscow. It was to be his last public appearance.

Although he was alienated towards the end of his life and ultimately fell silent, Mayakovsky was prophetic when he wrote that the power of his voicewould “reach you across the peaks of ages, / over the heads / of governments and poets.” He remained greatly revered in Soviet Russia, and had streets, metro stations, ships and even planets named in his honor; his brooding statue still watches over former Mayakovsky Square (now Triumfalnaya Square), one of the largest in Moscow.

Read more about the final days of Russian writers:

Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov

Nikolai Gogol and Anton Chekhov

Alexander Blok and Nikolai Gumilev

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox