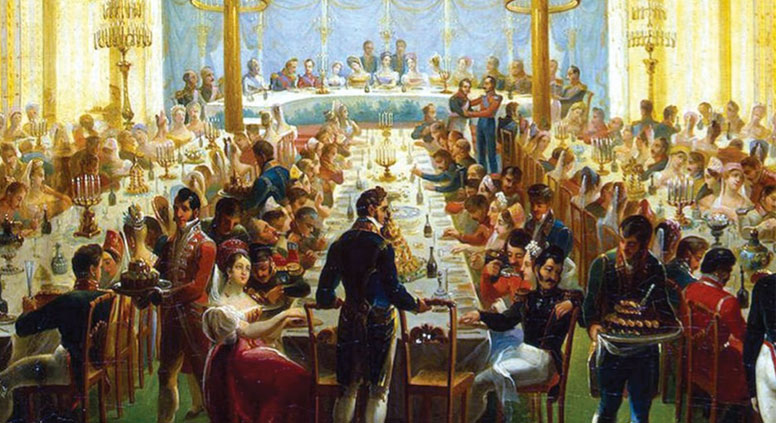

Dining with nobility in the heyday of the Russian Empire

|

| Source: Amazon.com |

The Russian nobility are well known for their opulent lifestyle, but now, almost a century after they were swept from power, readers can learn more about what this privileged elite ate and perhaps even try their hand at some recipes.

The delicious main courses in “High Society Dinners: Dining in Tsarist Russia” are based on a series of handwritten menus for dinners with nobleman Petr Pavlovich Durnovo in 1850s St. Petersburg. Translator Marian Schwartz points out that these are the years of “Anna Karenina” and “Oblomov,” and Yuri Lotman’s introductory essays are liberally garnished with literary allusions, from “Eugene Onegin” to “War and Peace.”

Literary cookbooks are currently in fashion, with recipes in the style of Charles Dickens, Jane Austen or Edith Wharton filling the shelves of bookstores. This book, first published in Russian in 1996, predates the trend and goes beyond it into an immersive exploration of social history.

New York-based Darra Goldstein, who has written several books about Russia, including four cookbooks, edited this newly translated tome, which was the work of the late Yuri Lotman, a celebrated cultural historian, and his one-time student Jelena Pogosjan, now a professor at the University of Alberta.

To read that the Durnovos, Prince Volkonsky and other guests ate turtle soup, stuffed pike-perch, meatballs in sour cream, goose with apples or roast hazel grouse already brings the past to life. Lotman’s notes, ably supplemented by Goldstein, add recipes, costumes and the hot topics of the day, from Emperor Alexander II’s trip to Berlin to President James Buchanan’s views on territorial expansion, as seen by Russian newspapers like The Northern Bee.

Lotman follows each menu with extracts from newspapers, letters and diaries to form a patchwork quilt of linked texts that is more than the sum of its parts.

An international menu

Marian Schwartz describes translating “High Society Dinners” as “a crash-course in food studies.” If the book is challenging, it is because Lotman’s own writing is digressive and analytical. His discursive style “works better in Russian than in the no-nonsense English language,” Goldstein writes in her introduction. She urges patience, insisting that the digressions “add social texture to the narrative.”

The internationalism of the 19th century Russian aristocracy is reflected in the menus. Windsor soup (a Victorian concoction of beef, root vegetables, cream and macaroni) could be followed by Russian-style sturgeon, French-style peas and Vienna torte (a confection of sponge cake, jam, jelly and champagne). In contrast, for the far less well-traveled Soviet reader, Lotman glosses words like meringue and gâteau, but assumes their readers are familiar with Coulibiac (fish pie).

Even as these glory days of fine dining were in full swing, with foreign affairs supplying a dramatic backdrop, the shadow of cataclysmic, future domestic events falls across the table. Lotman closes the book with a quote from Pavel Durnovo’s diary about Estonian riots in June 1958: “They say … the peasants wanted to take over the land,” he writes. “This is a step towards the people’s liberation and the nobility’s ruin.”

Read more book reviews and food recipes

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox