Let’s go, Revolution: Jazz poet Langston Hughes’ adventures in 1930s Russia

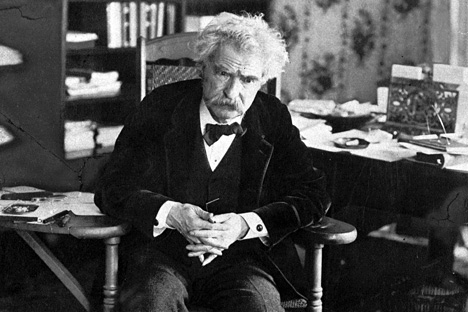

Langston Hughes. Source: Getty Images

Langston Hughes. Source: Getty Images

Langston Hughes (Feb. 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was one of the foremost 20th-century American poets and is credited with creating jazz poetry, which borrows heavily from the syncopated rhythms and sense of improvisation that are key to the musicality of jazz. When, in the early 1930s, he was invited to work on a movie in Moscow he was delighted. At the time, Hollywood “was still a closed shop” for African American writers, and his memoirrecalls that the invitation “seemed to open a new door to me.” He took the opportunity to explore the city, excited to discover this “capital of the new world,” in a “land where racial prejudice was reported taboo.”

Stranger in Moscow

Hughes was not disappointed by Moscow. “Of all the big cities in the world,” he noted in I Wonder as I Wander, “Muscovites seemed to me the politest of people to strangers:”

“Folks went out of their way there to show us courtesy. On a crowded bus, nine times out of ten, some Russian would say, 'Negochanski tovarish – Negro comrade – take my seat!'”

While in Moscow, Hughes befriended several high-profile figures, including Emma Harris, an African American from Dixie who had married a Russian nobleman during the Tsarist regime. “Emma knew all about black markets – and speakeasies,” Hughes remembered. “In a city where almost nothing was open after midnight, Emma could always find a place to drink.”

To Hughes' surprise, Harris was homesick for America. Yet he was certain she would be shocked if she returned. Comparing his treatment in the Soviet Union with America, Hughes hoped communist regimes might end racial segregation and inequality. In A Negro Looks at Central Asia, he explains that he hoped to “discover how the people live and work,” comparing their lives with “colored and oppressed people” in other parts of the world.

Hughes wrote several political poems during his trip. “Good Morning, Revolution” imagines unity among workers across the world. “I been starvin' too long,” announces the poem's final verse, ending with the rallying call “Let's go, Revolution!” Such poems were much criticized in the U.S.; Hughes' biographer Arnold Rampersad describes an editor later accusing him of subversive activities, saying that “Russia would be a good place for Hughes.”

Into forbidden territory

The movie project ran into difficulties, including a script by “a famous Russian writer” which Hughes found “improbable to the point of ludicrousness.” It was eventually cancelled, and Hughes applied for a press pass to visit Turkmenistan, an area considered “forbidden territory” to many foreign visitors at the time. This was “a land still in flux,” he explains in I Wonder as I Wander, where “Soviet patterns were as yet none too firmly fixed.”

At first, the trip eastwards was carefully regulated by officials. But Hughes broke away from the troupe in Ashkhabad, leaping off the train at “a wooden depot in a dusty desert.” Here, Hughes befriended the Hungarian journalist Arthur Koestler, who was drawn to his room by the sound of jazz records playing. Although jazz was officially taboo in the Soviet Union, his records proved popular throughout his travels. “A good old Dixieland stomp can break down almost any language barriers,” Hughes observed, declaring that “I wouldn't give up jazz for a world revolution.”

In Invisible Writing, Koestler described Hughes as an “innocent abroad,” whose approach was “humanitarian” rather than political. They certainly had different approaches. “To Koestler,” Hughes explains, “Turkmenistan was simply a primitive land moving into 20th-century civilization. To me it was a colored land moving into orbits hitherto reserved for whites.” Hughes was “shamed into action” by Koestler's journalistic vigour. After they met, he began taking notes on “the only kind of notebooks available in Ashkhabad, oilcloth-covered with lined yellowish paper.”

Hughes did recognize problems with bureaucracy and deprivation. He was shocked by poverty in the ancient city of Merv, and called the village of Permetyab “a distant outpost of hell.” In a filthy guest house which reminded him of “cheap Negro hotels in the South,” Hughes cleaned his room with an old shirt and “a scrap of my precious American-made soap.” But he was thrilled by a trip to a collective farm, a “green and leafy” oasis. “I was suddenly happy,” he recalls in I Wonder as I Wander, “gazing at a whole new world of fascinating people.”

Although Hughes' accounts of the Soviet Union are often idealistic, they offer a unique insight into a part of the world few foreign travellers experienced at the time, vividly recalled by one of America's finest poets.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox