Chekhov’s censored early work finally published

Anton Chekhov by Osip Braz, 1898. Source: wikipedia.org

The Prank is the collection of stories that Anton Chekhov hoped would kick-start his career as a writer. Censored in 1882, now, 133 years later, the book he intended has finally been published – in English - with the subtitle “The Best of Young Chekhov”. The collection has never appeared before, even in Russian, although many of the stories in it are well known, and only two of them are new to translation.

Chekhov the chameleon

This selection of playful tales sheds new light on the young writer, a confident foretaste of recurring themes: misogyny, pretension and lack of compassion. Chekhov appears as a chameleonic jester: here in the guise of a Spanish translator and there as a scientific journalist; a malapropistic, elderly landowner, writing to his educated neighbor, or a cantankerous mother complaining about marriage. By the end of the book, his romantic pastiche swallows its own tail in an ecstasy of meta-fictional, pre-modernist surrealism.

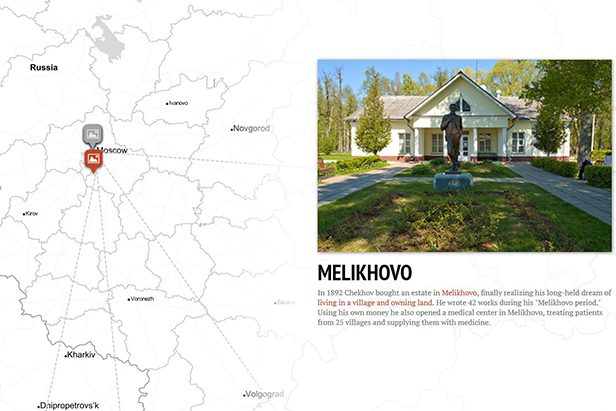

In the 1880s Chekhov was in his twenties and training to be a doctor. To pay the tuition fees of his Moscow medical school and support his family, he wrote a series of comic short stories under pseudonyms like Antosha Chekhonte. Already published in humorous magazines, this was to be his first book, with the revised stories illustrated by his brother Nikolai. The imperial censor rejected the manuscript, and it languished in a dusty office until a Soviet scholar rediscovered it in the 1970s.

“This is Russia all right”

|

| The Best of Young

Chekhov, NYRB Classics, 2015 |

Translator Maria Bloshteyn, who has cleverly replicated the freshness of Chekhov’s prose or the deliberate awkwardness of his parodies, explains in her excellent introduction how subversive these stories were. At first glance Chekhov’s flippant fables, some little more than extended jokes, seem inoffensive: an overblown imitation of Victor Hugo’s tempestuous style, an amusing mockery of Jules Verne, a letter from a confirmed bachelor explaining why his many engagements (to “Olya, Zhenya, Zoya”) had never ended in marriage (goose bites, hiccups, literary pride).

But look more closely and these seemingly innocent scenarios expose hypocrisy and corruption: a father tries to bribe a teacher into giving his son a better grade; a train carriage becomes a corrupt and stinking social microcosm, with passengers paying the conductor to dodge the full fare. One traveler observes: “darkness, snoring, stale tobacco and rotgut – this is Russia all right.”

In the opening story, an apartment block full of “artists’ wives” suffers from frenzied, baby-waking singers, sleep-inducing literature or painters who demand their wives pose naked by the window. The protagonist, Alphonso Zinzaga, (Chekhov loves ridiculous names) is a young novelist: “very famous (only to himself)”. The Portuguese setting is transparent as Chekhov gleefully satirizes Moscow’s narcissistic bohemians.

Newcomers to Chekhov might find this slim volume an amusing appetizer; for those who already know and love his work, it adds an interesting layer to the portrait of the ironic, melancholic doctor we think we know. Confirmed theatrical Chekhovophiles will scour these pages for a glimpse of the later playwright, with his tragicomic psychological observations. When an old man is abandoned to the elements in St Peter’s Day, a story about a group of drunken hunters, it foreshadows the end of Chekhov’s last play. The Cherry Orchard closes with an elderly servant locked in the deserted house.

As Bloshteyn hopes, these stories have “the effect of an early photograph of someone met in middle age.” Unfamiliar at first, closer inspection shows us “smiling eyes” and recognition: “Yes, that’s him! Of course that’s him.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox