Bulldozing the orchard: Echoes of Chekhov in Sam Shepard's plays

Sam Rockwell, Nina Arianda and Tom Pel during the Broadway Opening Night performance Curtain Call for 'Fool For Love' at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, on Oct. 8, 2015 in New York City. Source: Getty Images

Getty ImagesSam Shepard said recently about Chekhov that he was "not crazy about him as a playwright". Initially it does seem that they are very different writers, but there are, however, significant similarities in their exploration of the themes of property, family and the past. It seems that Shepard is sometimes arguing with Chekhov within his work about these issues.

A more savage Cherry Orchard?

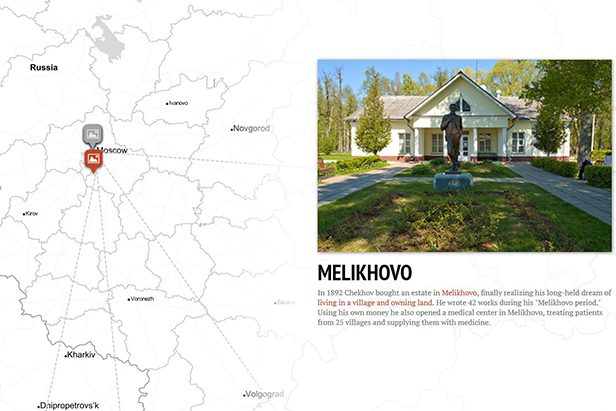

On its premiere in 1978 one critic described Shepard's play The Curse of the Starving Class as "The Cherry Orchard returning as farce". Shepard sets his play in an American country house, with an 'avocado orchard' which is being bought up by dubious property developers and lawyers to be turned into low-rent housing.

“The Cherry Orchard” performance, Moscow, 1979. Source: Valerya Christoforova / TASS

The constant references to the orchard - Wesley talks of "bulldozers crashing through" it - suggest that Shepard is quite deliberately calling Chekhov's play into the audience's mind. In both plays, as the critic Stephen Bottoms said, "the family home is invaded". In Shepard's play the house is literally disintegrating; the father Weston has drunkenly smashed the front door down, which allows the property lawyer and debtors to come in easily. A diseased lamb even starts to live in the sitting room, and at the end, instead of the sound of the tree struck by the axe, we hear a car exploding outside. Chekhov has his sympathetic usurper Lopakhin inside the house from the beginning, he is the first person the audience sees, and the owners return, only to be slowly sidelined.

This external march of progress is set against a kind of stasis in the lives of the families. Chekhov shows the old Russian aristocracy, especially in the figure of Lyubov Andreyevna, struggling to adapt to being pushed out of their home by the nouveau riche. But in Shepard it is the working class, the 'starving class', who are being forced out by the professional class. It is, as Shepard scholar James A. Crank said, "a re-imagining of The Cherry Orchard", but in the context of America in the 1970s, and perhaps more cruel and savage as a result; we are watching poor people and even animals fighting over space.

Absent fathers

For both playwrights, the home is a battleground, with the attacks coming not just from outsiders but also from within the family itself. This family civil war is waged over the past, which is represented by problematic father figures for both authors. Chekhov's fathers are notably absent.

The family is sent into turmoil by the removal of the traditional authority figure. The first word of Three Sisters is “Father...”, and he is there, like the striking of the clock, haunting proceedings. The death of the father in The Cherry Orchard seems to have precipitated the family's decline, with the son drowning a month later, and then Lyubov running off to Paris. The father is a symbol of a past that cannot be recaptured.

|

| The Cherry Orchard. Source: Open source |

A recent version of Chekhov's early play Platonov by Helena Kaut-Howson was called “Sons Without Fathers”. This could be a description of much of Shepard's work too, especially True West. His fathers have often inexplicably disappeared or they are present but in unusual ways.

In The Late Henry Moss and Fool for Love, the father is a ghost wandering around the stage, haunting the present. In the latter play the ghost of the father says "You can't betray me! You gotta represent me! You're my son!"

In The Curse the father is a wandering drunk, often unconscious or elsewhere for much of the important action. Significantly, the son turns into his father, dressing up in his clothes and being mistaken for him by his own mother and the debtors. It seems that for Shepard the father represents a past that cannot be escaped; the sins of the father will be visited on the son, the father is a “curse” in the blood that cannot be cured.

Fool for Love is currently showing on an open run at The Manhattan Theatre Club in New York

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox