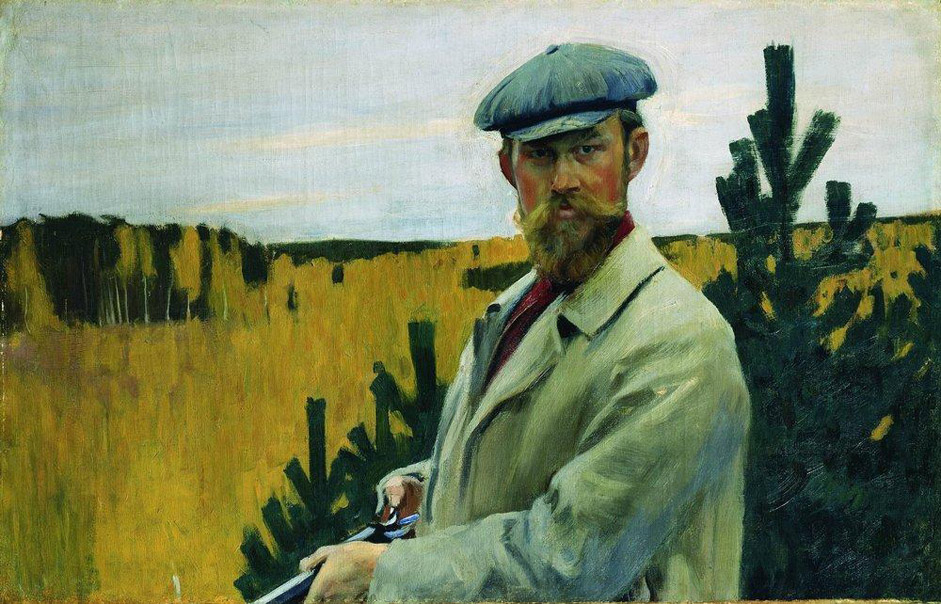

Born into a poor family, Boris Kustodiev (1878-1927) was prepared for a life in the priesthood. Having enrolled at a seminary, in 1896 he left for St. Petersburg and entered the Academy of Fine Arts. // Self-portrait during the hunt, 1905.

Boris Kustodiev

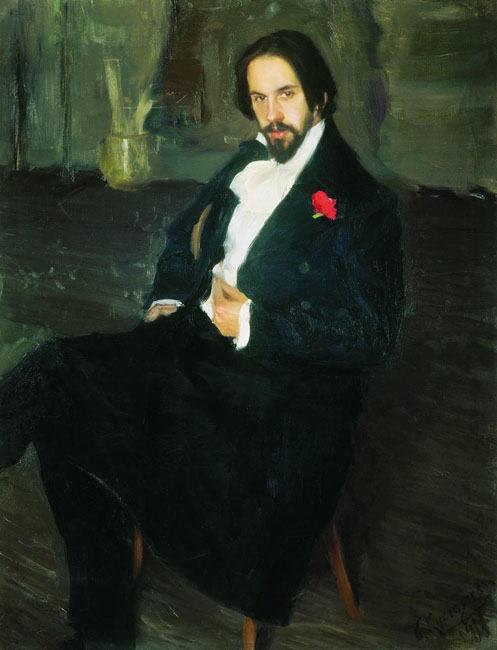

There, he worked in Ilya Repin's studio, and was so successful that the latter invited him to be his assistant. Kustodiev displayed a gift for portraiture, completing a series of first-class works; for example, his portraits of Ivan Yakovlevich Bilibin, 1901.

Boris Kustodiev

In 1903, Kustodiev graduated from the Academy. His diploma piece earned him the right to travel abroad to Paris. Paris afforded the artist an opportunity to study French painting, which he put to good use in his delightful painting "Morning" (1904). But less than six months later, he returned to Russia, having become homesick.

Boris Kustodiev

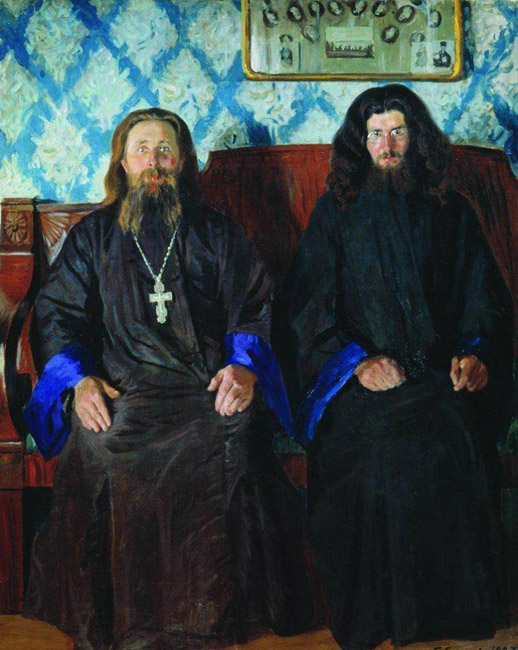

After returning to Russia, Kustodiev turned his attention to book design, and worked as an illustrator for various satirical magazines during the first Russian revolution. But painting remained his primary occupation. He produced a series of notable portraits, in particular "Portrait of a Priest and a Deacon" (1907), which later became generalized social and psychological types.

Boris Kustodiev

At the same time, he worked with passion on works depicting the old Russian way of life, mostly provincial. He unveiled some fascinating stories, full of piquant detail, in his multi-figure compositions "Trade Fair", 1906, 1908, and "Village Fête", 1910. // "Spring", 1921.

Boris Kustodiev

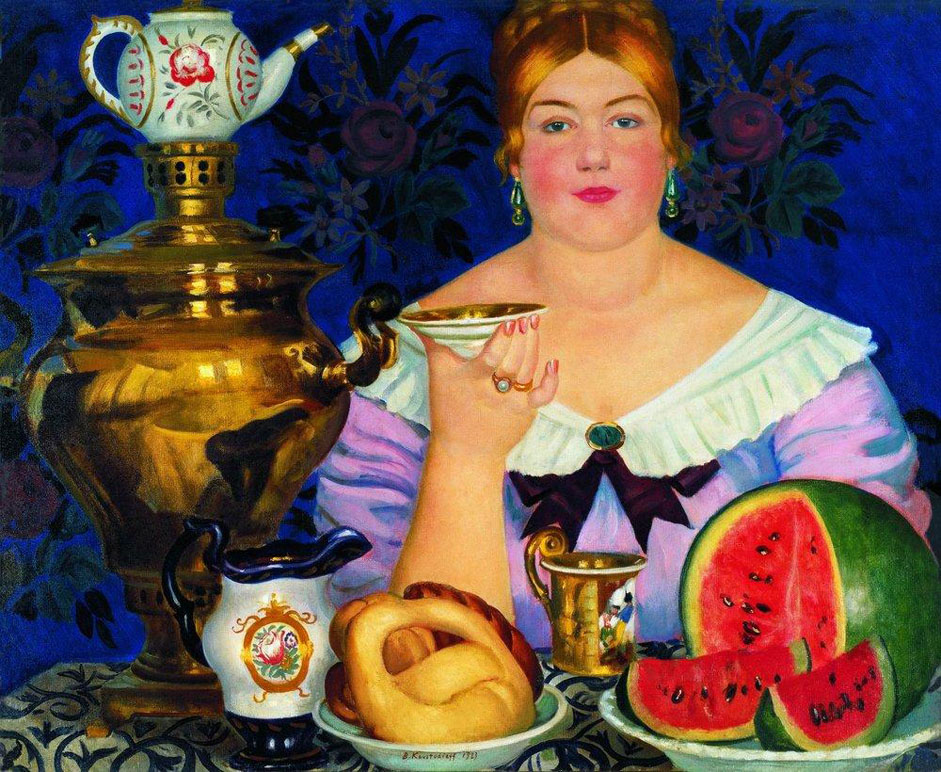

He recreated characteristic Russian female types in the pictures "Merchant's Wife," "Girl on the Volga," "Beauty," (1915), imbued with the author's admiration and mild irony. His painting became increasingly colorful as it began to resemble folk art.

Boris Kustodiev

In 1915, the artist finished his famous masterpiece "Beauty." In this work, as in "Russian Venus," through the force of talent he creates a new artistic reality. The picture is rich in texture and captivates the onlooker with its skillful representation of various room-filling materials and the greatest treasure of all — the female body.

Boris Kustodiev

"Merchant's Wife", 1915, and "Beauty" display Kustodiev's know-how. They demonstrate the master's poise and maturity, as well as visibly expressing his discernment of human beauty. Perhaps this expression is somewhat caricatured, but such irony often acts as a safeguard against overly "refined" criticism.

Boris Kustodiev

The result was "Maslenitsa" (1916) — an idyllic panorama of this Shrovetide celebration in a Russian provincial town. Kustodiev worked on this cheerful picture in wretched circumstances: as a result of a serious illness in 1916, he was confined to a wheelchair and tormented by recurrent pain.

Boris Kustodiev

Despite that, the last decade of his life was unusually productive. His output included two large paintings depicting a celebration held in honor of the II Congress of the Communist International, numerous portraits, sketches of Petrograd in festive mood, pictures and artwork, and set designs for 11 theater productions.

Boris Kustodiev

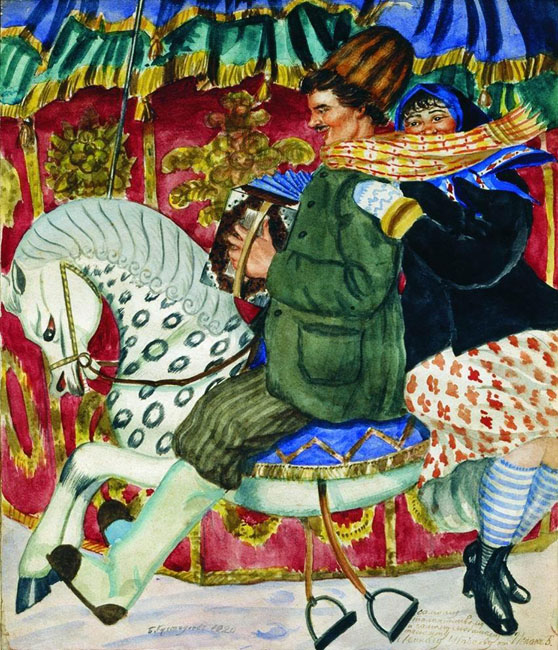

Kustodiev found time to devote himself to more intimate pursuits, such as his nostalgic love of old Russia, which he sought to recreate in a variety of paintings, watercolors, and drawings. He composed variations on the theme of maslenitsa in the paintings "Circus Tents" (1917), "Maslenitsa" (1919), and "Winter. Shrovetide Festivities" (1921).

Boris Kustodiev

Kustodiev: "I do not know if I have made and expressed all that I wished: love of life, joy, vivacity, my beloved 'Russianness' — that was the only 'subject' of my pictures. // "Merry-go-round"

Boris Kustodiev

He vividly portrayed the quiet provincial life in "Blue House," "The Fall," and "Day of Pentecost" (1920), executed a series of 20 watercolors, "Russian Types" (1920), and resurrected with maximum authenticity his own childhood in a sequence of pictures, as well as in the series "Autobiographical Drawings" (1923), similar to the Pushkin sketches.

Boris Kustodiev

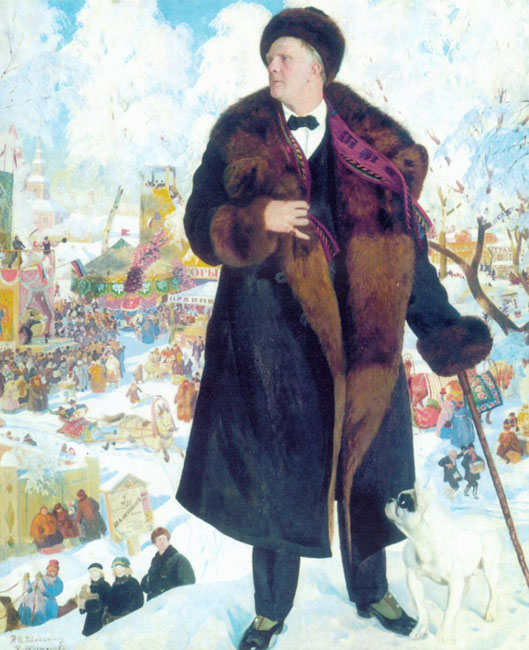

Kustodiev's possessed an amazing ability to create the image of a person out in the open air. Chaliapin was so huge that the workshop was too small for him. The artist was unable to accommodate his entire figure. The canvas was tilted so that the infirm Kustodiev could paint in a sedentary position. It was the work of intuition, created by artistic instinct. Kustodiev never saw the portrait in its entirety from a sufficiently objective viewpoint, and therefore had no idea how the picture had turned out. But Chaliapin rated it very highly.

Boris Kustodiev

"In my works, I want to pay homage to the Dutch masters, their attitude to one's native way of life, -" he said. "They have lots of anecdotes, but this anecdote is very ‘convincing’ because their art is warmed by a simple and passionate love for all that is visible. They say that the Russian way of life is dead... What nonsense! One's mode of living cannot be destroyed, because it is a person..."

Boris Kustodiev

Kustodiev's energy and vitality were striking. Although wheelchair-bound, he attended theater premieres and even made long trips around Russia. As his illness progressed, the artist had to work on a canvas hanging over him almost horizontally in such close proximity that he was unable to see the work as a whole. Kustodiev was not yet fifty when he passed away. // "Russian Venus", 1926

Boris KustodievAll rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox