No conflict between Lenin and the Madonna in Petrov-Vodkin's world

After Boys, Petrov-Vodkin created Bathing of a Red Horse, a work that holds a special place in his art and marked the beginning of the 1910s in Russian art. Work on Bathing of a Red Horse, however, started in the winter of 1911 and early spring of 1912. // Bathing of a Red Horse, 1912

Free Photo

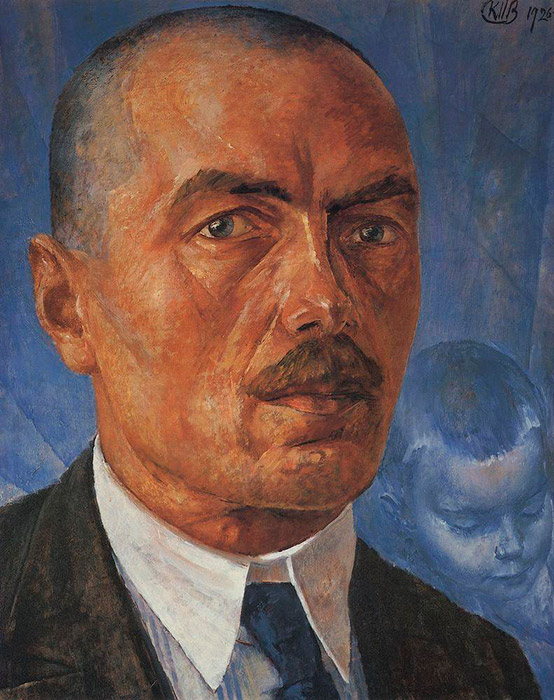

135 years ago, on November 5, 1878, in the provincial town of Khvalynsk, a baby boy was born to a shoemaker and maid: Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878-1939), one of the most original Russian artists of the first decades of the 20th century. His works caused fierce controversy, ranging from enthusiastic praise to disdainful ridicule. // Self-portrait, 1927

Free Photo

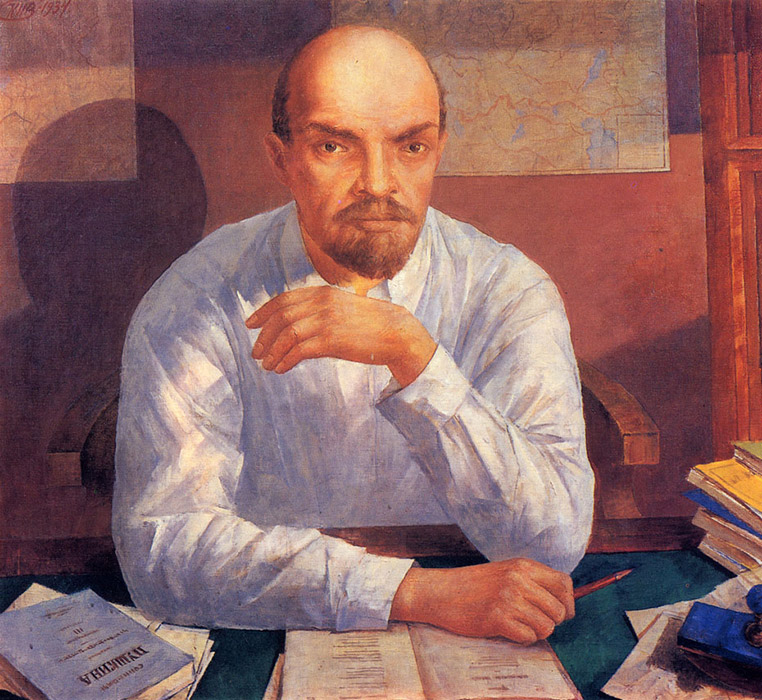

Petrov-Vodkin was an outstanding painter, unsurpassed draftsman, original theorist, natural-born teacher, gifted writer, and eminent public figure. He was a multitalented individual, a one-of-a-kind artist, and the son of his times, displaying various interests: from painting Russian icons to Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Russian Revolution. // Portrait of Lenin, 1934

Free Photo

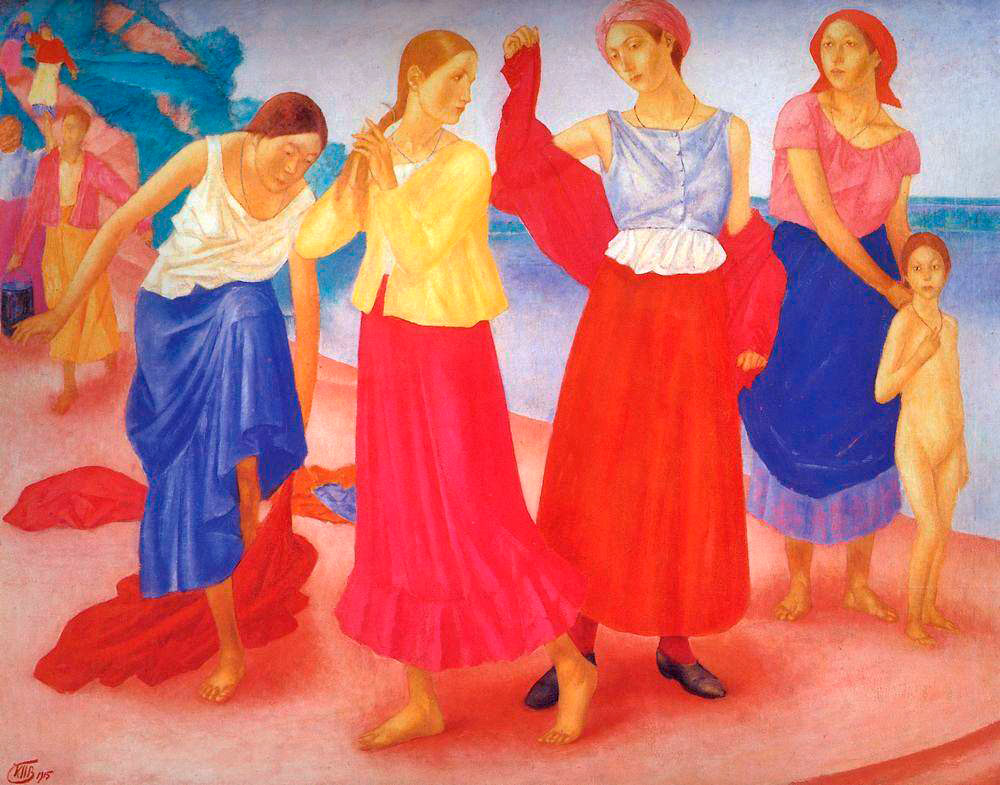

His emergence as an artist occurred at a time when picturesque symbolism was on the decline and avant-garde painting had not yet manifested itself so clearly. Hostility was growing at the heart of the then-main artistic association, the Union of Russian Artists, centered around the animosity felt by its Saint Petersburg members towards their Muscovite colleagues. // Girls on the Volga, 1915

Free Photo

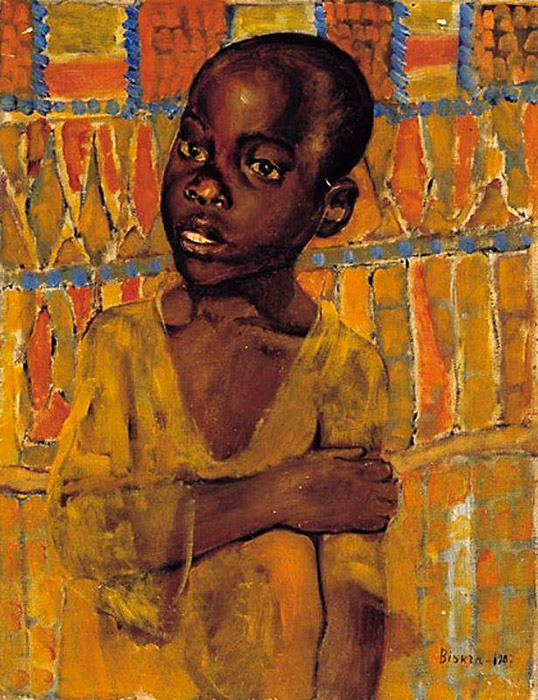

With the assistance of Sergey Makovsky, publisher of the journal Apollo and an admirer of the self-taught Petrov-Vodkin’s work, the large Salon exhibition was organized in Saint Petersburg. The works from his “African” cycle at the Salon exhibition seemed especially peculiar. Unlike many of his contemporaries who had decided to refuse the principle of figurative painting, Petrov-Vodkin strove to preserve the traditional form of painting, synthesizing neo-classicism’s objectivity of image with the symbolist convention of rhythm & color. // African boy, 1908

Free Photo

This led to Russian avant-garde painters of the early 1910s perceiving Petrov-Vodkin’s painting as outdated and academic, while the public at-large considered him to be the same kind of formalist as the avant-gardists, if only slightly different. Only a few art critics and experts understood the extreme importance of Petrov-Vodkin’s best artistic accomplishments. His 1910 painting, Sleep, enjoyed great success. // The Dream, 1910

Free Photo

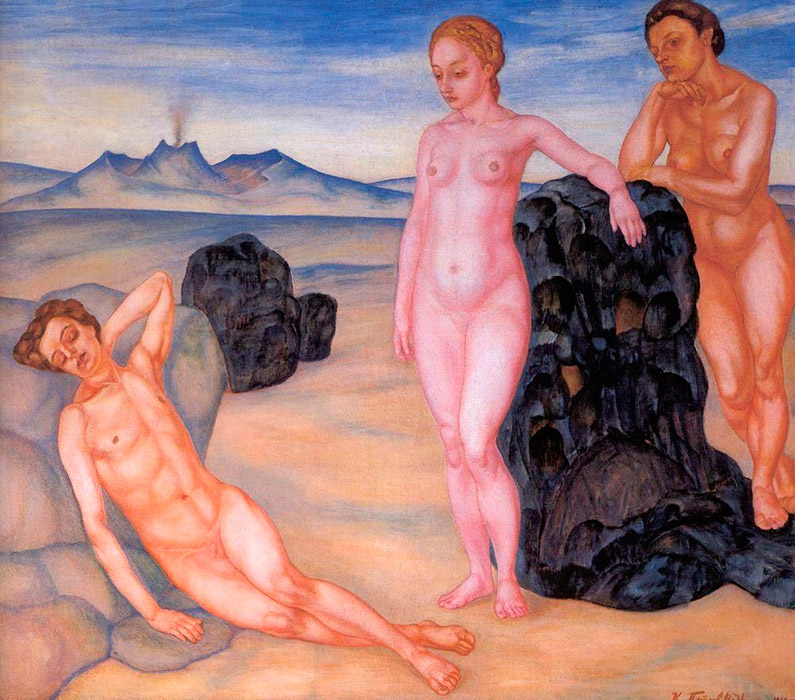

If such paintings as Elegy, Shore, and even Sleep could be created outside Russia as well, then the overwhelming majority of Petrov-Vodkin’s works from the 1910s pertain to the most striking manifestations of his artistic vision’s specific national features that are organically tied by their roots to ancient Russian art. // Shore, 1908

Free Photo

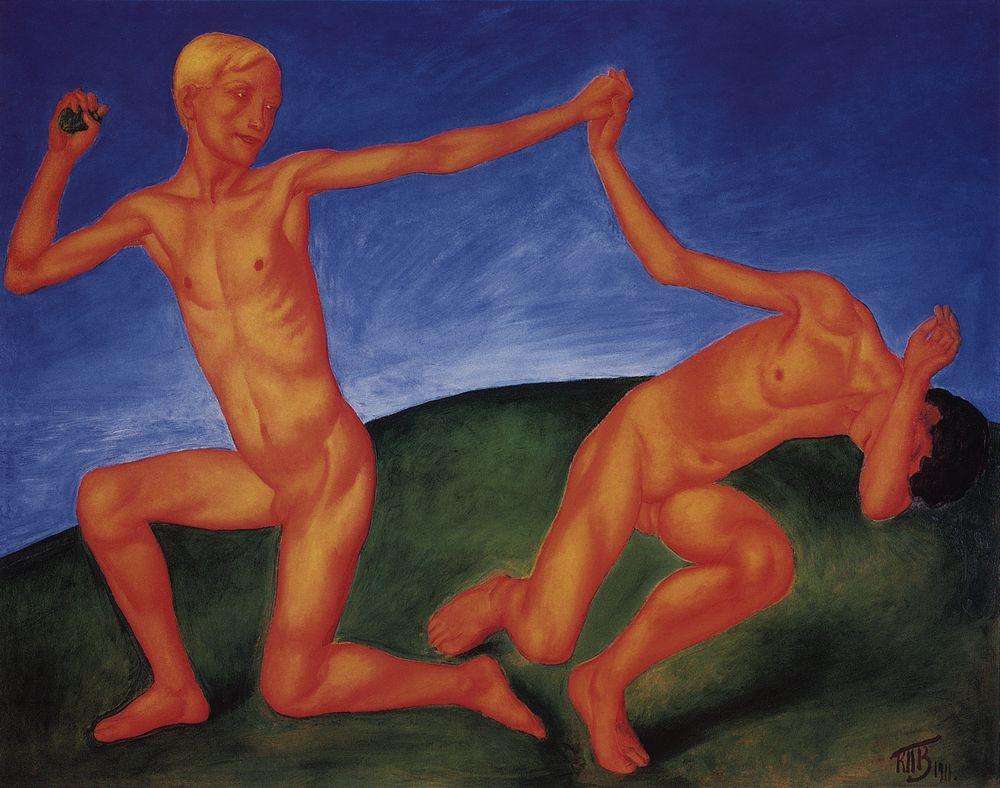

The first and most emblematic painting of this type was Boys (or Boys at Play, 1911). Recalling his work twenty years later, Petrov-Vodkin said that Boys was “painted as a funeral march” for the deaths of Valentin Serov and Mikhail Vrubel. This painting, a celebration of youth and life, was a response to Russian art’s recent loss of two of its greatest masters. Boys’ main concept, in particular its color scheme, inevitably calls to mind Matisse’s famous mural, Dance, to which Petrov-Vodkin remarked, “You know, I think that we in Russia paint better than Matisse.” // Boys at Play, 1911

Free Photo

In 1912-1913, Petrov-Vodkin’s art powerfully included the most important theme that defines its content: motherhood. The national type of a Russian woman, perceived to be like his painting in the depths of Russia and on the Volga, became the brightest example of Russian fine arts of the 20th century. // Mother, 1915.

Free Photo

The artist also embodies a completely earthly, humanly emotion, sublime only in its spiritual purity and power, in the religious theme that interested him at the time, this being Our Lady, Tenderness of Cruel Hearts, 1914-15. // Tenderness of Cruel Hearts, 1915

Free Photo

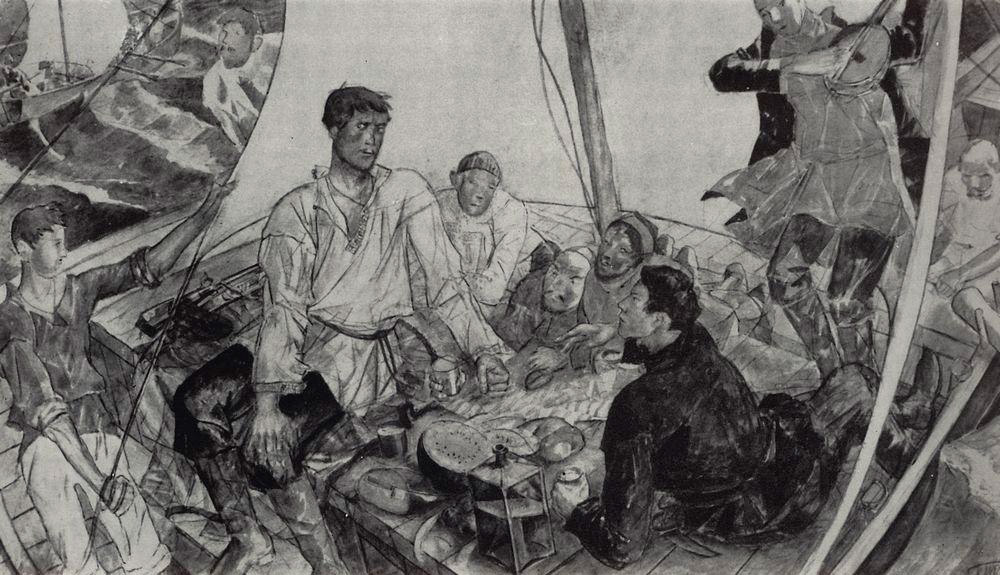

In honor of the anniversary of the October Revolution, dozens of Petrograd’s (now Saint Petersburg’s) were decorated with ornamental constructions based on sketches by artists of various disciplines. Among them were four enormous panels by Petrov-Vodkin. One of these panels was dedicated to Stepan Razin, while the other three were painted based on themes from Russian epics and folktales. // Stepan Razin panel scetch, 1918

Free Photo

The first painting of Petrov-Vodkin’s Soviet period was 1918 in Petrograd, which, in its time, was called the “Petrograd Madonna”. In this painting, the artist strives to embody the new essence of the mother figure: her urban, proletarian version. // Petrograd Madonna, 1918

Free Photo

After the Battle was constructed in the clash of contrasting scales of ocher tones of the foreground and the blue background that had already been seen in Petrov-Vodkin’s paintings. It contains a prediction of the future possibilities of cinema—its retrospection and combination of multi-temporal levels. // After the Battle, 1923

Free Photo

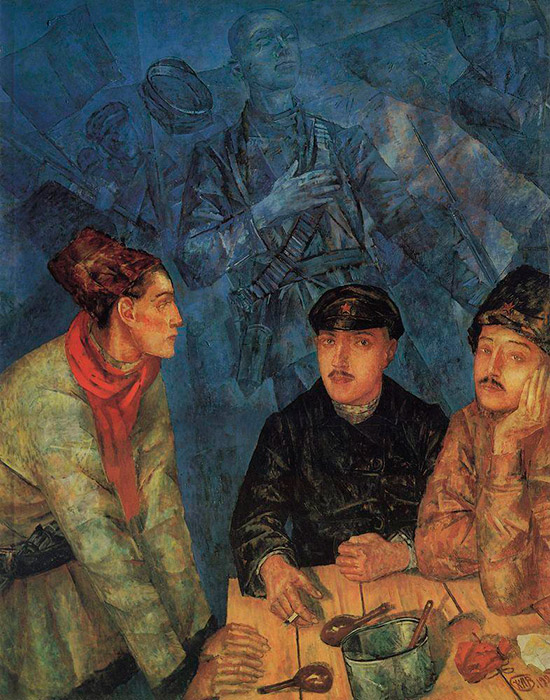

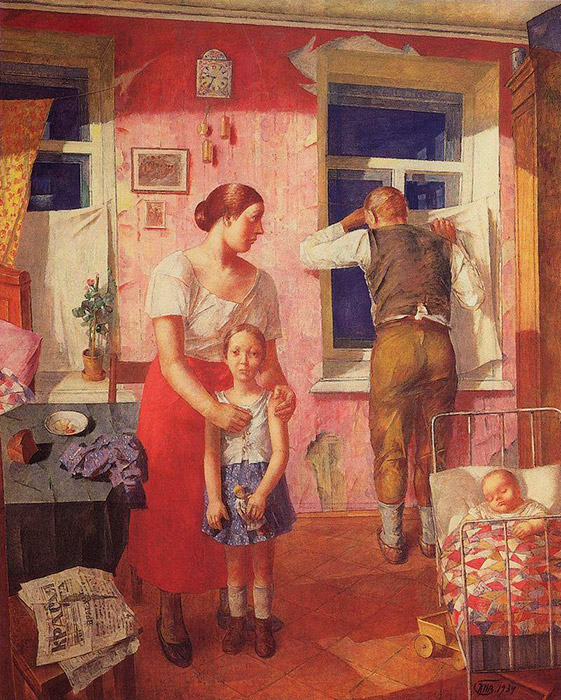

Around 1934, Petrov-Vodkin returned to active painting and created one of his best paintings of his late period in which a revolutionary theme reemerges. // Alarm, 1919.

Free Photo

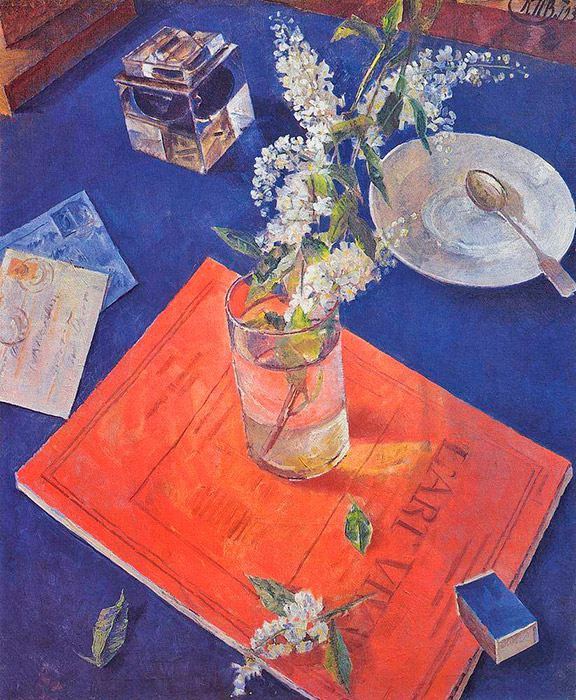

After his death, the artist’s name was crossed out from Soviet art. In the subsequent quarter century, it seemed that people had forgotten about Petrov-Vodkin and his paintings had almost disappeared from museums’ collections. However, sooner or later, true art receives recognition. For Petrov-Vodkin, this time came in the second half of the 1960s. // Bird cherry in a glass, 1932

Free PhotoSubscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox