Ded’s Dead: The End of a Mafia Era in Russia?

The single 9mm bullet which ended the life of notorious mafia boss Aslan Usoyan also ended an era. Although there are still gangsters who call themselves vory v zakone, (“thieves within the code”) this Soviet-era underworld fraternity is all but extinct.

The rigid code of behavior, the almost monastic self-discipline, the easy willingness to go to prison rather than betray a promise, they are all part of the Russian mafia’s mythological past. The future, on the other hand, belongs to a very different breed of gangster.

Usoyan, actually an ethnic Kurdish Yezidi from Georgia, was widely known by his criminal nickname Ded Khasan (‘Grandfather Khassan’), and was about the last surviving senior underworld figure of the old school.

He was inducted into the ranks of the vory v zakone inside a prison camp in 1985, and since then had built a multi-ethnic gangster network that spanned much of the country. At 75, he had long since given up directly involving himself in criminal activities.

Instead, he played the elder statesman: identifying opportunities, resolving disputes, accepting tribute and, when need be, asserting his authority over his subordinates and even to outsiders.

In the process, needless to say, he made enemies, not least the Georgian gangster Tariel Oniani (‘Taro’), who is in prison but none the less powerful for it, and the up-and-coming Azeri Rovshan Janiev. But perhaps more to the point, he did not really change with the times.

No more code

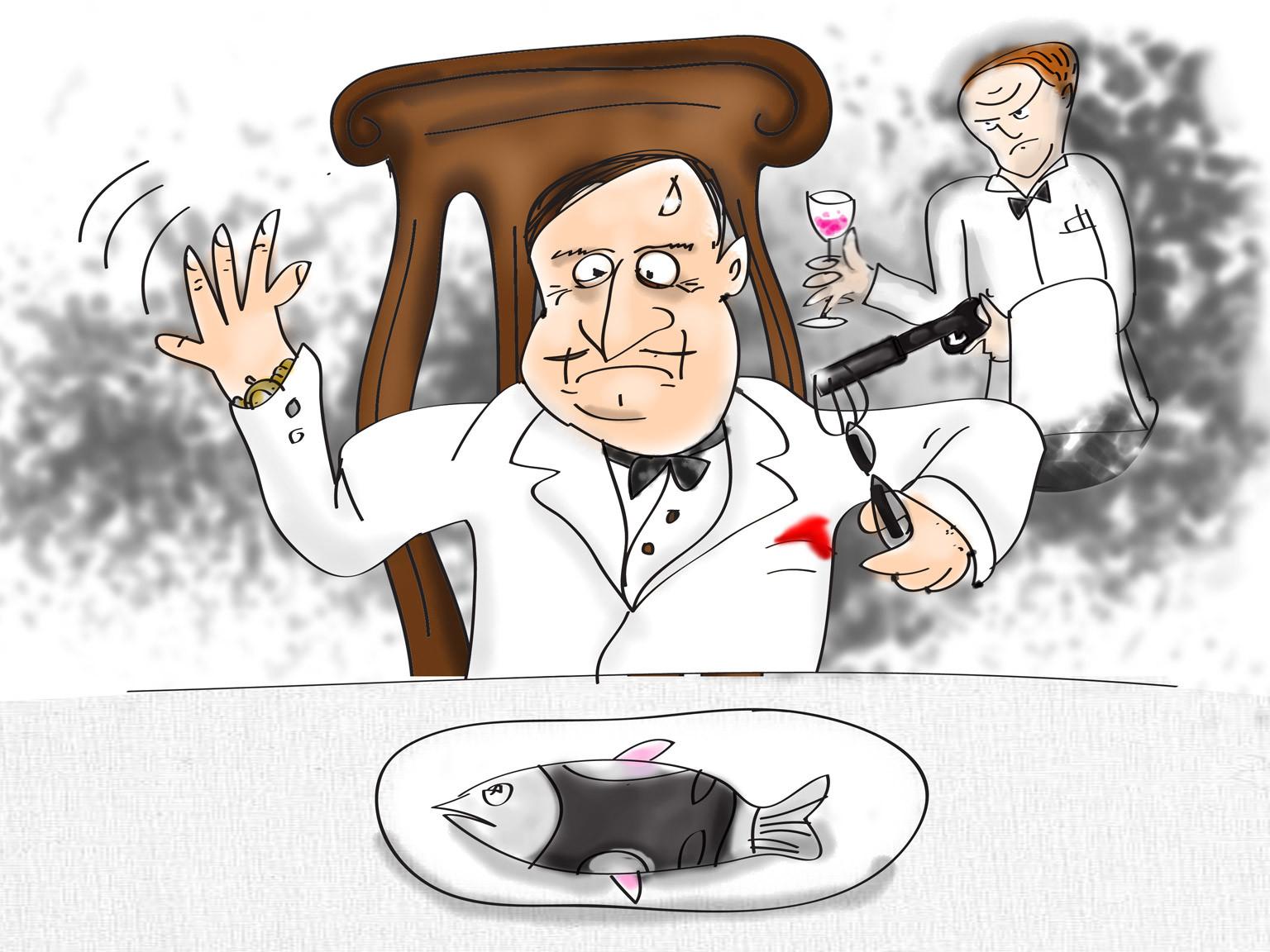

Russia’s underworld is no longer one in which a deal concluded with a handshake is sacrosanct, in which godfathers can flaunt their status (Usoyan would regularly hold court in Moscow’s restaurants) and in which it is enough just to be a gangster.

Oniani and Janiev are technically both vory, but like most who still claim the title, they does not follow the code and would not be recognized as one by the traditionalists of the Soviet era.

The new generation crime bosses, the so-called avtoritety (‘authorities’) are a more polished and cynical breed. Not for them the elaborate tattoos and colorful gangster nicknames.

They are criminal-businessmen, who combine and mask their underworld ventures with legitimate ones and who build close alliances with local and national political elites. Unlike Usoyan, who largely confined his operations to Russia (with some links to Ukraine and Georgia), their ambitions are international.

They are also predominantly ethnic Russians, rather than the Georgians, Chechens and others from the south, who still cling to older, macho traditions.

Gangsters tamed

But Usoyan’s death also potentially brings to an end another era, too: more than a decade of underworld peace. The 1990s saw Russia ripped by violent underworld conflicts.

Gangs fought to occupy the vacuum left by the collapse of the Soviet state and snap up territory and resources, while the government lacked the resources and the will to fight back.

Even before Putin’s accession to the presidency in 2000, the conflicts were beginning to be resolved. However, he also accelerated this process, both by providing more funds to the police and also making it clear that he would not tolerate overt gangsterism on the streets.

Organized crime was by no means defeated, but it was tamed. It adapted to the new order and while it continued regularly to turn to violence to settle scores and punish challengers, it did so in a much more precise way.

Afghan heroin

However, this new order may be close to breaking. A new generation of gangsters want their slice of the cake. Once-powerful gangs were impoverished in the 2008 financial crisis.

Conversely, other gangs are suddenly rich because they are benefiting from the increasing amounts of Afghan heroin flowing into and through Russia. This so-called “Northern Route” into Europe and China already accounts for almost one-third of the total. The foundations of the old status quo are coming into question.

Usoyan’s successors are almost inevitably going to strike back at whomever they believe responsible for his murder. His network may splinter along factional or ethnic lines or face an internal struggle for succession.

He wanted his nephew ‘Miron’ to take over in his stead, but there are many who wonder whether he is up to the job. If gangs drawn predominantly from the Caucasus seem in disarray, this might prompt their ethnic Russian rivals to turn on them.

Given the precarious nature of the current balance of power in the underworld, any of these developments could provide the spark that ignites a whole new round of bloody mob wars. Even if it does not, though, it is likely that there will be a reordering of the crime world, as the avtoritety complete their rise to ascendance. One way or the other, the era of Usoyan and the vory v zakone is over.

Mark Galeotti is Professor of Global Affairs at New York University. His blog, ‘In Moscow’s Shadows,’ can be read here.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox