Revising the concept of Eurasia

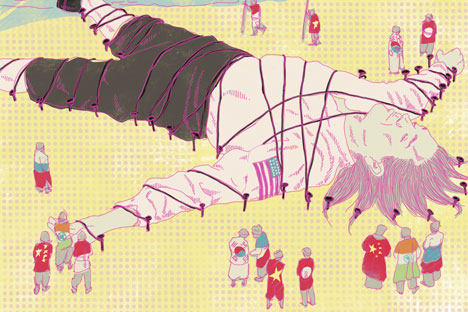

Click to enalrge the cartoon. Drawing by Natalia Mikhailenko.

The “little Eurasia” of Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union is only a part of the vast but increasingly crowded regiont that is set to become the center of world development in the 21st century. We need to think broadly in terms of the entire region in order to pick through its new geopolitical context.

At the turn of the 21st century, Eurasia (which had always been a primarily geographical notion) was transformed into an increasingly interconnected economic, political and strategic concept in the context of globalization. Within Eurasia, we see how the weight and role of key components of the world’s largest region is changing.

Basically, the dynamic center of the region is moving eastward, while the conflict zone is actually and potentially moving to the south and to the east. This circumstance has far-reaching consequences for all countries, though this is especially true for Russia: the country has common borders with all the forces in Eurasia and, for the first time in 20 years, is again trying to be an active player there.

The emergence of a “new Eurasia” calls for a revision of established concepts. The collapse of the Soviet international system at the turn of the 1990s brought about a major redistribution of power in Eurasia. Numerous “power vacuums” appeared.

The United States, which emerged as the sole superpower at the end of the Cold War, became an active player on the territory of the former Soviet empire. In the east of the region a new economic giant – China – is rapidly growing. The fact that China, Europe, India and Russia were preoccupied with their internal problems effectively left the U.S. as the only active player in Eurasia. In the 1990s, Washington strengthened its positions in Europe through the expansion of NATO: the collective security alliance transformed from a regional defense organization into a structure for operations outside of the region.

The 2010s brought a fundamentally new trend. Financial problems resulted in the U.S. defense budget not only stalling but even starting to shrink. America’s involvement in Eurasian conflicts is clearly on the decline. The country is pivoting toward Asia and the Pacific “to face China,” which means that the shrinking resources are being concentrated to respond to the challenge that Beijing presents to American dominance in East Asia and the Western Pacific.

The relationship between Washington and Beijing – major economic partners and, simultaneously, geopolitical rivals – has become the most important bilateral relationship in the modern world, around which Eurasian and, to a large extent, world politics are beginning to revolve.

China’s growing ambitions, backed up by the strengthening of its army, have not only complicated relations with the United States, but they have also noticeably increased tensions between Beijing and its neighbors: Japan, India, Vietnam and the Philippines, which are all countries that have close, long-standing economic relations with China. The future will see increased Chinese influence in those regions rich in resources that China’s economy needs: in the Middle East, Central Asia, strategically important transit routes from the Gulf of Aden to Malacca Strait and, later, the Northern Sea Route via the Arctic.

Japan ceased to be strategically independent in 1945, hiding under the U.S. umbrella. However, with China continuing to grow, it is no longer enough to rely on Washington. As early as the late 1990s, then Japanese Prime Minister Hashimoto proposed the idea of a Eurasian foreign policy – not as a counterweight, but as an addition to the Japanese-American alliance, which Tokyo still regards as key. Under the current conditions, the Japanese “Eurasian” policy may acquire an equally important strategic element. The geopolitical realities objectively prompt Tokyo to transform its relations with Russia in a positive way.

Thanks to its economic achievements, South Korea has reached a level where its foreign policy is beginning to rapidly expand its horizons, and these horizons include Eurasia. Experts, as well as a number of politicians in Seoul, are discussing the possibility of developing political and economic ties with Russia as a way of complementing its alliance with the U.S. and its economic integration with China and Japan.

During the 45 years of its existence, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has emerged as an effective model of economic, political and cultural integration – the only one of its kind in Asia. ASEAN includes Indonesia, which is potentially another great Asian power. So far, however, the Association has been a community of equals. ASEAN countries have created a regional forum in which the U.S., China, the European Union and Russia are partners.

India is in the midst of a difficult period of emergence as a regional power center. At present, India is still a regional power in South Asia; nonetheless, New Delhi obviously seeks to go beyond this framework. The country has staked a claim to a greater role in world affairs, but the country’s political class has yet to form a hierarchy of interests, a distribution of resources and a strategy to match this new role.

In the context of the Islamic revolution in the Middle East that began in 2011, Turkey is playing a greater role and assuming greater responsibilities. The inability of the EU to integrate Turkey (or at least to work out a coherent policy with regard to the country) has shown that Europe is unable to act as a strategic player. Berlin has been trying to play a new role in relations with Moscow, Beijing, Ankara and other capitals. Great Britain, in that case, is likely to occupy a middle position between the new “tight Europe” and the United States.

Dmitry Trenin is the director of the Carnegie Moscow Center.

First published in Russian in VPK Daily.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox