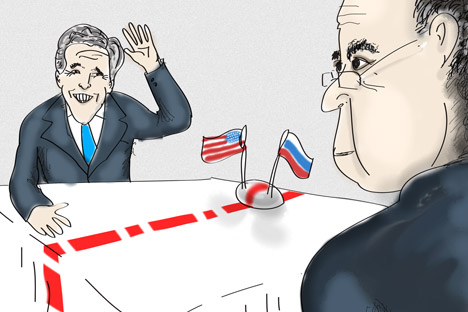

Click to enlarge the cartoon. Drawing by Niyaz Karim

Last week, the U.S. Senate confirmed John Forbes Kerry, a Democratic senator from Massachusetts (1985-2013) as the 68th United States Secretary of State. Kerry became the second U.S. senator in a row—after Hillary Clinton—to assume the top American diplomatic post. Both enjoyed impressive support from their Senate colleagues: the vote for Kerry was 94-3, an almost exact match to the 94-2 vote cast for Clinton four years ago. Characteristically, both Kerry and Clinton have had serious presidential ambitions: Kerry lost the 2004 general election to George W. Bush, whereas Clinton, defeated in the 2008 Democratic primaries by the current president Barack Obama, is still considered a formidable candidate for the Democrats in 2016.

Virtually all experts agree that Kerry’s appointment to lead the Department of State means the continuity of U.S. foreign policy during Obama’s second presidential term. Some differences in Kerry’s and Clinton’s approaches to world affairs are to be expected, though. Over the past couple of years, driven mainly by Clinton’s personal views—and, perhaps, future career considerations—American diplomacy has been increasingly focused on humanitarian issues, including the issue of human rights. This trend is unlikely to be sustained under Kerry, who seems to prefer addressing more traditional international problems, such as the Middle East peace process and Iran’s nuclear program.

Moscow was visibly pleased with Obama’s choice of Kerry as the next American counterpart to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. In Russia, Kerry is widely recognized as a proponent of positive U.S.-Russia relations; everyone remembers his spirited support for the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty back in the fall of 2010, when Kerry was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Additionally, it is anticipated that Kerry, who is always in control of his words, will refrain from repeating the questionable statements allowed by Clinton in the closing weeks of her secretaryship, including her description of Moscow’s efforts to promote greater economic integration in Eurasia as “a move to re-Sovietize the region.”

The new concept of the foreign policy of the Russian Federation, a document yet to be signed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, places Russia’s relations with the United States as only a relatively moderate foreign policy priority – third after political and economic integration in the post-Soviet space and relations with the European Union. But in reality, Russia’s foreign policy is perennially locked on what is going on in United States, an unhealthy tradition sometimes bordering on obsession.

Two factors can account for this bias. First, the Russian leadership is still psychologically refusing to accept the fact that Russia lost its status of one of the world’s two superpowers. One of the few things that in their mind keep supporting the notion of Russia’s “greatness” is the fact that together with the United States, Russia possesses about 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons. Moscow needs dialogue with Washington—especially at the highest levels – to remind to the rest of the world (and its domestic audience) that Russia is still an important actor on the world stage.

The second factor is the persona of Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov. Having spent the formative years of his diplomatic career in the United States as Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations, Lavrov tends to reduce the whole body of Russian foreign policy to a Moscow-Washington bilateral relationship, and so far has shown little desire to switch to the mundane task of integrating political and economic space in Russia’s “near abroad.” Interestingly, except for a few months in 2004, Lavrov has had to deal with two female U.S. Secretaries of State: first Condoleezza Rice, then Hillary Clinton. On occasions, his relations with the ladies were less than charming. In 2008, being reportedly offended by Rice’s criticism of Russia’s military actions in Georgia, Lavrov turned down her offers to meet to discuss a peace agreement between Moscow and Tbilisi. Last year, in a move that some Russian media interpreted as a show of strength, Lavrov refused to take Clinton’s calls on the ground that he was “busy.”

It remains to be seen which adjustments Lavrov will have to make to work with Kerry, given Kerry’s somewhat aristocratic demeanor and a clout of a decorated war veteran. (Lavrov, for his part, never served in the military). Of course, Russia may try to preserve the gender balance and replace Lavrov with a female minister of foreign affairs. To be sure, this will not solve all the problems U.S.-Russia relations have been facing as of late. On the other hand, why not to try something new?

Eugene Ivanov is a Massachusetts-based political analyst who blogs at The Ivanov Report.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox