Syria: A guidebook for tomorrow's diplomats

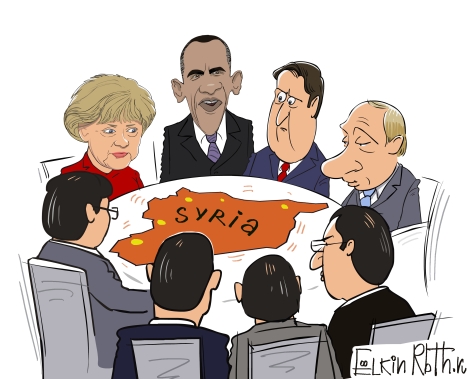

Drawing by Niyaz Karim

Some international crises become real-life manuals for students of diplomacy and international relations, Syria being a distinctive example. It is an ideal case study, especially now that everyone is looking forward to the upcoming peace conference.

“If you want peace, prepare for war” is an ancient adage — but one that is still true today, as sabers rattle ahead of the hypothetical roundtable, which is expected to gather all stakeholders and help them decide how to move on.

The EU decided not to extend the embargo on arms supplies to Syria (to Syrian rebels, to be more precise), although the UK and France were the only ones actively calling for abolition of the limitations, while other member-states voiced their doubts as to whether going deep into the civil war was a rational move.

There is a clear political message in the declaration about the willingness to support the opposition. The statement indicates that the power scenario remains a realistic option. In other words, if there is no agreement, there will be war to the bitter end.

Russia has essentially the same logic, for it neither admits nor denies supplies of S-300 missile systems and other advanced arms to Damascus.

Related:

The Syrian need for Russian arms

The elusive solution to the Syrian crisis

Russia, Syria discuss deadlines for MiG-29M/M2 fighter deliveries

This approach may have an inverted effect, though. So far, one gets the impression that each conflicting party is drawing a single, simple conclusion from looking at the political games played by major powers: Whatever happens, no one will give up on them, so it is worth going on fighting.

Both Assad and his opponents are well aware that their foreign patrons — Russia and the West, respectively — cannot stop supporting their allies without suffering a serious blow to their image.

It is a matter of principle for Moscow, Washington and Syria. Russia backs the secular rulers (however undemocratic) and non-interference.

The West, for its part, is busy choosing between ideological schemes featuring a “revolting nation” and “bloody dictator” and the wish to adopt the standard conflict-resolution model that crystalized following the Cold War: Choose the “right” conflicting party and help it come to power. To give up on allies is not just a move to put the eggs pragmatically in a different basket but an ideological concession that will affect self-esteem.

The purpose of the peace conferences of the past — including the Yalta and Potsdam conferences — was to divide up the world. In recent history, peace conferences of this kind have mostly centered on the Balkans: the Dayton Agreement on Bosnia of 1995 and the Kosovo crisis of 1999. Because these two may be used as models for resolving the Syrian crisis, it would be helpful to analyze both of them.

Dayton would be a positive option. The external players managed to get the warring parties around the negotiating table and make them agree a new map of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Optimists hope that the Geneva-2 conference on the Syrian crisis will be just as successful as the Dayton meeting.

Pessimists refer to the Rambouillet Conference on Kosovo in early February 1999: a result of enormous diplomatic efforts that had no tangible outcome, because tensions had reached the limit.

We should not be drawing direct analogies with Syria, as there are too many specifics; yet rapid escalation is quite likely, unless the peace conference achieves a breakthrough (which is currently impossible).

The Syrian crisis is fundamentally different from anything that has ever happened previously.

Whenever major world powers get involved in a local conflict and champion the peace process, they always pursue their own interests, having in mind a clear picture of future benefits. Backed by the United States, Western European nations made changes to the strategic landscape of Europe on the basis of the assumptions that predominated after the Cold War.

When it comes to Syria, it is impossible to understand the direct and specific interest of the United States, Europe and Russia, apart from the image issues mentioned above.

An extension of the sphere of influence to the Middle East is an almost utopian idea. External forces are desperately looking for the right response to what has already happened and a way to adapt to the new realities, which have been reshaped beyond their will and wishes: So what sort of strategy are we talking about?

Even the nations that have applied interests in the region — Syria’s neighbors, from Iran to Saudi Arabia and Qatar — are keeping silent about the conference. They make virtually no statements, but whether the warring parties will negotiate ultimately depends on these countries.

The big games played by big international players used to be interwoven with smaller plots devised by local players — but big plans always remained front and center. The situation is different now: Local processes are quite logical, while the big fish are involved somewhere on a parallel track, and those who lead often switch places with those who follow.

The Syrian crisis is an inexhaustible source of experience for historians of the future, but, for diplomats of today, it is an almost impossible mission.

Fyodor Lukyanov is the chairman of the Presidium of the Council for Foreign and Defense Policy.

The opinion is first published in Russian in Gazeta.ru.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox