Drawing by Alexei Iorsch

Drawing by Alexei Iorsch

Drawing by Alexei Iorsch

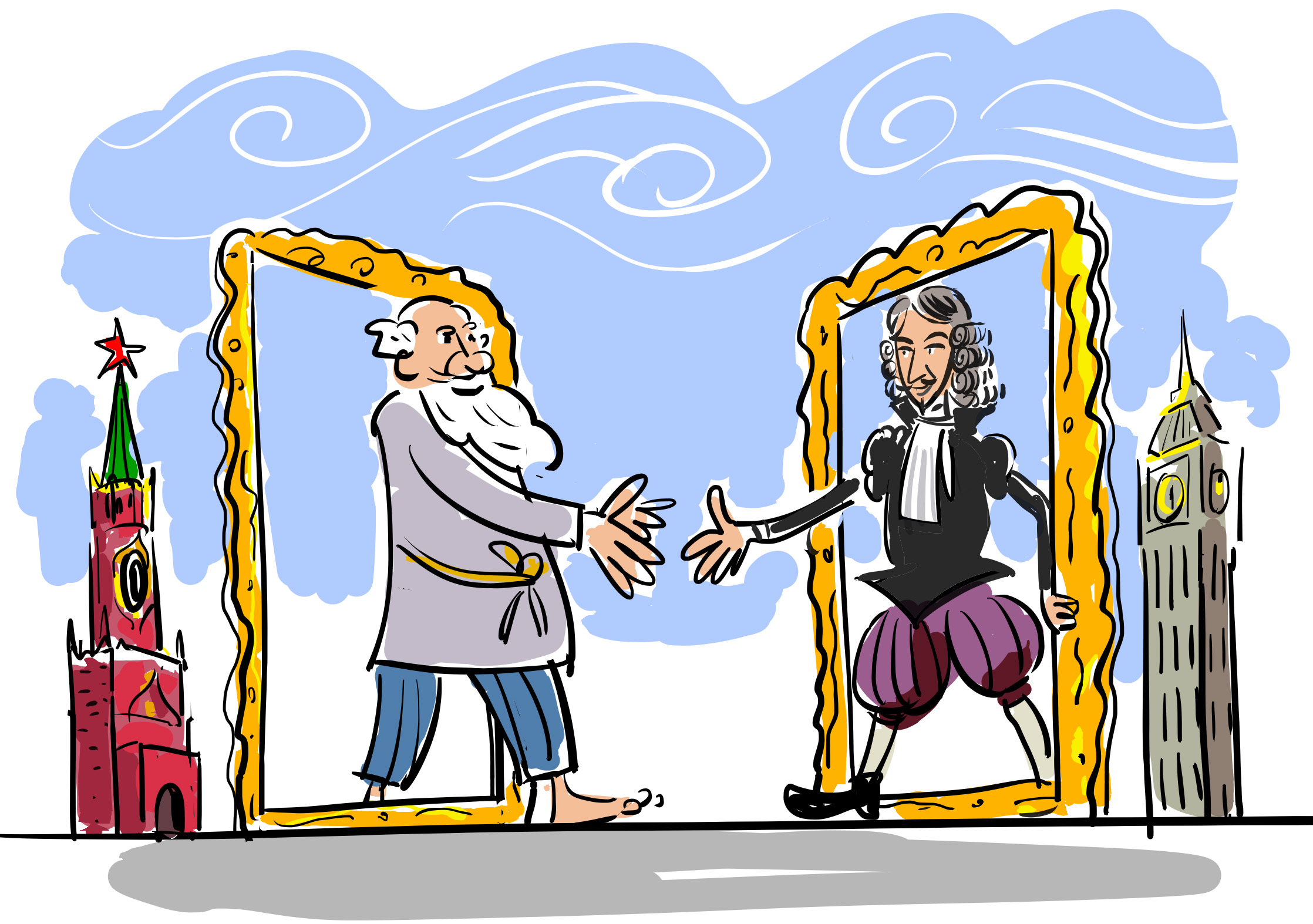

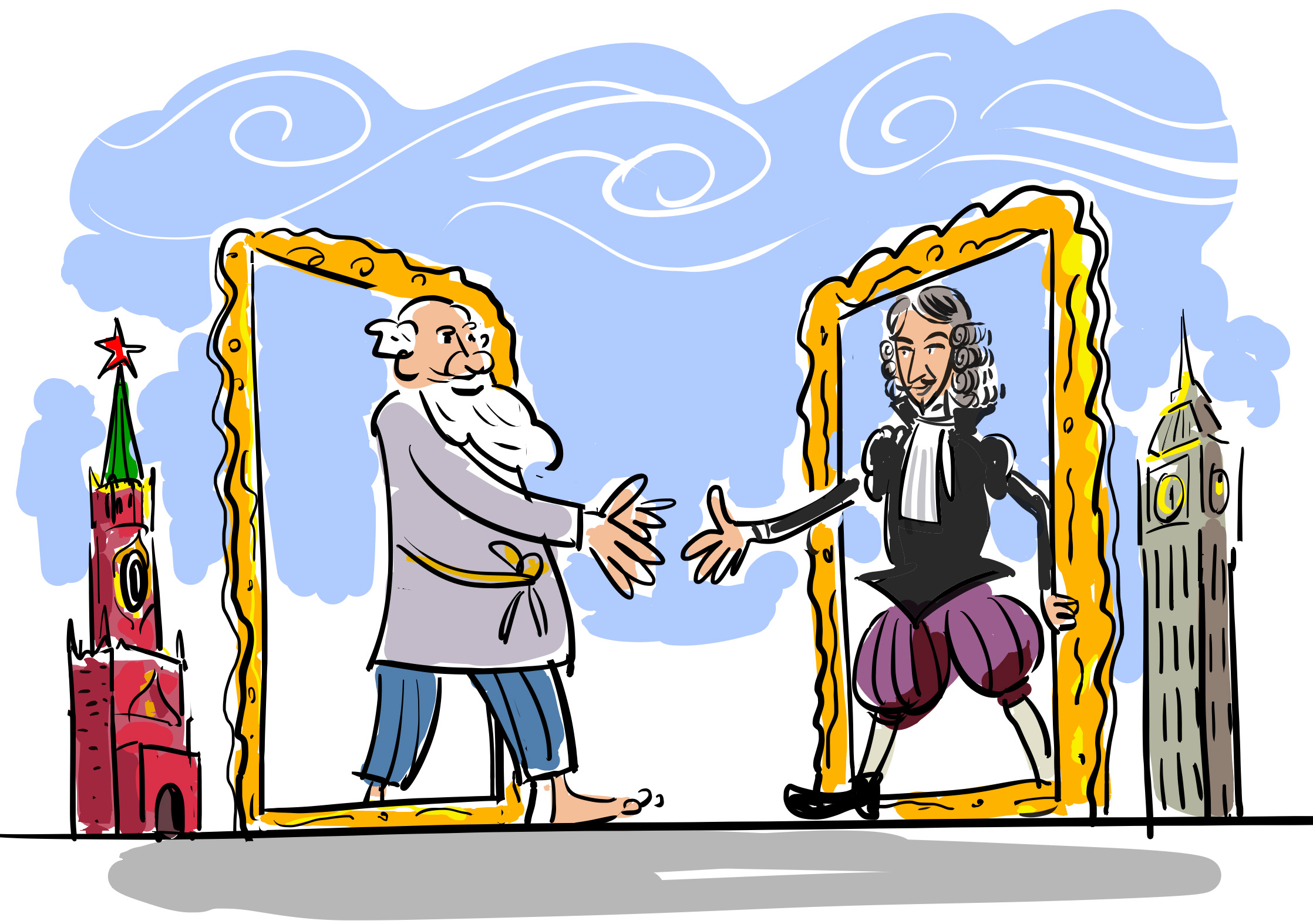

Two households, both alike in dignity… From ancient grudge break to new mutiny…” Applying Shakespeare’s words from Romeo and Juliet to the current state of relations between London and Moscow wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration.

Still, another poet, the Russian Sergei Yesenin, noted: “When face to face/We cannot see the face./We should step back for better observation.” And while we have stepped back politically, we now have a clearer vision of the mutual cultural attraction. With diplomatic and economic contacts stalled, we realize the importance of the humanitarian dimension, the people-to-people contacts that help us get over the adverse geopolitical weather.

This year has seen the centenaries of First World War events that fostered mutual understanding, like the Anglo-Russian Hospital, Russian Flag Day or the trip of Russian writers to Britain. And, 100 years on, our governments have had the political foresight to declare 2016 a Russia-UK Year of Language and Literature.

While the Russian program in Britain officially started on Feb. 25, the grand opening of in Russia happened a few days ago, with the launch of a National Portrait Gallery exhibition at Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery and coinciding with the Shakespearean anniversary.

Meanwhile, the parallel exhibition of the Tretyakov Gallery at the NPG has been a huge hit from its start on March 16, attracting up to 900 visitors a day. What is amazing is that the paintings now on display in London are not creations of the leaders of the Russian avant-garde, who are well known in Britain, but rather of painters who, while household names in Russia, are only now being discovered in the UK – Repin, Perov, Serov and others – unlike those who sat for them, including Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky and Akhmatova.

This is one of the main points this cultural season will make, i.e. to go beyond the canon to discover the riches of literature and art. This is why Russian writers come to the London Book Fair, both in print and in person, among them Andrei Gelasimov and Guzel Yakhina, who have their novels translated into more than 10 languages.

We aim to widen the horizons of the sophisticated British public on Russian literature old and contemporary, theater, cinema, art and history. Obviously, we want to encourage more Britons to study Russian, which is already as popular at A-level as German but still below the Cold War numbers. Then, oddly enough, many people who started learning the language for reasons we’d rather forget ended up falling in love with the Russian culture and people.

No introduction is needed for the Bolshoi Ballet (coming in July) or the Boris Eifman Ballet (December). The Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra will give concerts in virtually all of the major UK cities in October. It is refreshing to see new British takes on War and Peace on the BBC and Crime and Punishment at the Open Air Theatre near Tower Bridge this August. Our world views, as reflected in our cultures, differ; but still, time and again, we feel like sharing each other’s.

We are confident that the better we know each other, the better is the understanding. Over the past five centuries, Russia and Britain have been able to understand each other more often than one might think. There are many pages of common history to learn from, from Peter the Great to the Arctic convoys in the Second World War.

Researching them is an important task for scholars and volunteers from the recently formed Russian Heritage in UK committee. With assets like these, there is no doubt that when the time comes, we’ll have an overall relationship that our two great nations, sitting together in many world councils, deserve.

Alexander Yakovenko is Russian Ambassador to the United Kingdom. He was previously Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Follow @Amb_Yakovenko on Twitter

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox