Why were authorities slow to admit the truth about Chernobyl?

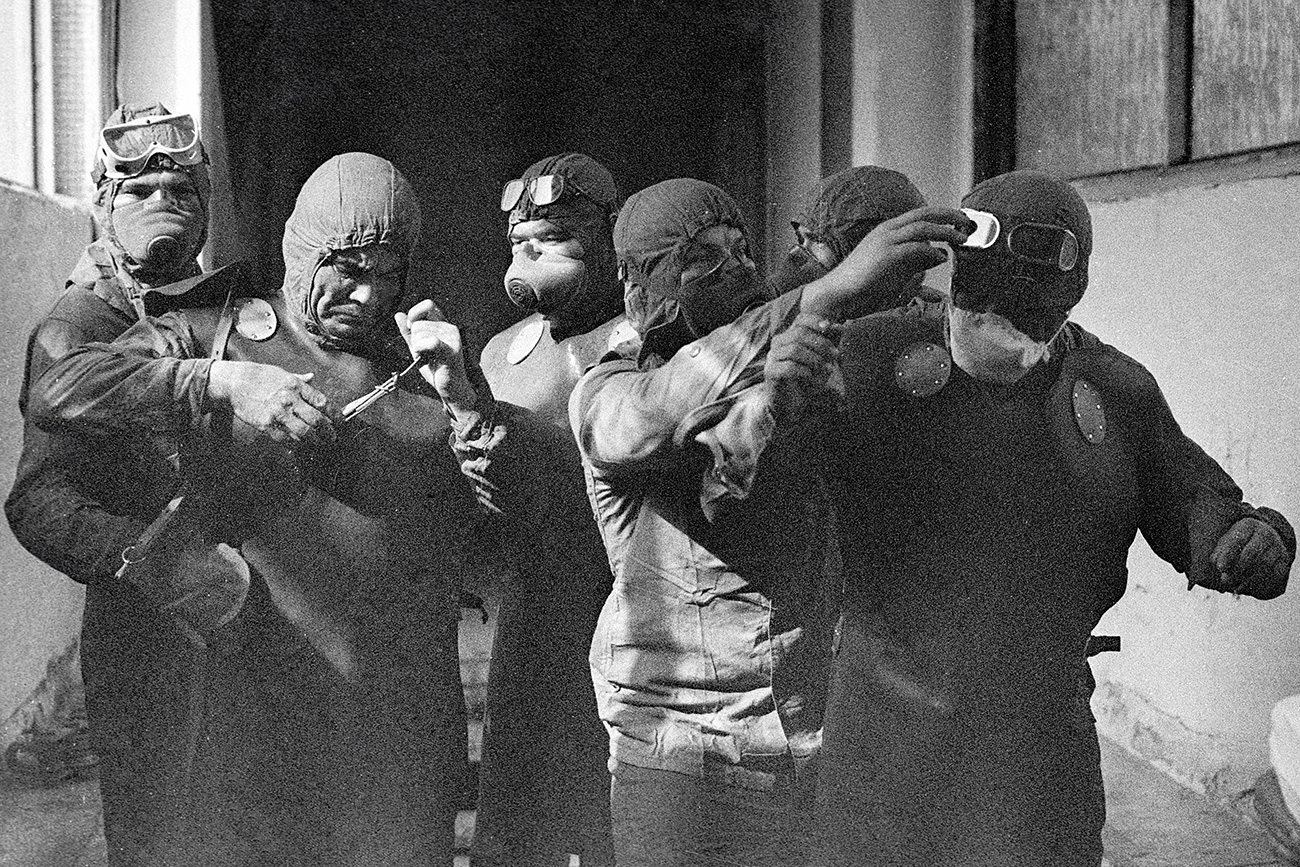

Treating the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant site with a decontaminating solution.

Vitaliy Ankov/RIA Novosti Treating the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant site with a decontaminating solution. / Photo: Vitaliy Ankov/RIA Novosti

Treating the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant site with a decontaminating solution. / Photo: Vitaliy Ankov/RIA Novosti

Pripyat was considered an exemplary Soviet town, and was a prestigious place to live because it was designated an economically advantageous place to work. There were 15 kindergartens, 25 shops, five schools, cafes, restaurants, a hospital, a hotel, a river port, a cinema and a swimming pool. More ominously, it also had a nuclear power plant that was one of the most advanced in the industry and which was the largest employer for the local population.

On the night of April 26, 1986, during a planned maintenance shutdown and subsequent scheduled experiment, two explosions rocked the facility. The first blast knocked out a concrete plate weighing 1,000 tons, and the second blast released 190 tons of radioactive material into the atmosphere.

Chairman of the Soviet government, Nikolai Ryzhkov, led the task force to clean up the horrible consequences of the accident. In 1992, during the so-called `trial of the CPSU' [Communist Party of the Soviet Union], he had to answer for decisions made that day in April 1986 and in the following weeks. Many still are debated to this day.

Nikolai Ryzhkov. / Photo: Maksim Blinov/RIA Novosti

Nikolai Ryzhkov. / Photo: Maksim Blinov/RIA Novosti

Deadly serious

"I remember that day well. It was a Saturday and I was getting ready to go to work. At that moment, Energy Minister Anatoly Mayorets called me on the government hot line and said there had been an accident at the Chernobyl plant but that he did not know the details. I told him to find out what had happened by the time I arrived at work.

"To be honest, I was far from thinking that the reactor had exploded. Accidents had happened there before - generators had broken down, turbines had broken down - all sorts of things had happened. And so I expected something similar. But when I was told it was a power unit, it was absolutely clear to me that the situation was deadly serious and exceptional. I immediately took action.

A group of liquidators ready to climb the top of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor after the disaster. / Photo: Igor Kostin/RIA Novosti

A group of liquidators ready to climb the top of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor after the disaster. / Photo: Igor Kostin/RIA Novosti

"Their opinion was the following: Since the town of Pripyat was in direct proximity to the nuclear plant, and 50,000 people lived there, the town should be evacuated immediately. I authorized an evacuation. Preparations for it went on all night, and at about two or three o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday, April 27, I was told there were no people left in Pripyat and only dogs were left running around."

Avoiding panic

"The Swedes were the first to register [the fallout]. On the night of April 26, their sensors recorded increased radiation and they concluded that there had been a leak somewhere. It's true. We only worked out what it was in the morning. But all the rest is fiction. No one concealed things from the population for three days. Yes, the information that people were given was very measured and controlled. But what were we supposed to do - shout to the whole country: `People, flee and save yourselves!?'

"Were we such idiots to specially create panic, so that hundreds of thousands of people would panic and run around in all directions, including in the direction where the radiation was coming from? No, we were not such fools. People had to be evacuated in an organized way. Not everyone knew what radiation was. There were lots of problems and questions what to do to counteract it. Those who lived in Pripyat mainly worked at the nuclear plant and realized perfectly well what radiation was.

"Two or three hours later, at about 11 a.m., I had already signed a decree for the creation of a government commission headed by my late deputy, Boris Shcherbina. At 3 p.m., the commission was ready; it was staffed by top specialists, and included scientists and heads of ministries. That same day, they flew to Chernobyl, and by Saturday evening they reported to me about what had really happened.

"I flew in on May 2, and travelled by car from Kiev. We stopped in some villages close to the affected area. An old woman came up to me and asked what was going on. I told her: 'It's contamination - it's radiation. You need to take care of yourself.' And she replied: 'What contamination? Look how clean the potatoes are.' This is how people thought - they didn't realize that death was hanging in the air.

"By May 2, we already knew the size of the affected area from several sources. Then, at a meeting in Chernobyl, I decided that everyone within a radius of 18 miles from Chernobyl should be evacuated. We placed a compass on the map and determined the radius at the farthest point. Late that night, when I was leaving Kiev by bus, I saw hundreds of buses already going in the opposite direction to evacuate people."

Stay and fight

"In fact, we didn't even have helicopters with anti-radiation protection. It was necessary to fly over the reactor. It was an ordinary helicopter, whose floor was lined with lead sheets - lead delays the penetration of radiation. We were dressed in white overalls and white caps, and we had Geiger counters in our pockets; that's all. When you're flying far from the reactor, it just clicks, but quietly. When you get closer, it begins to click more frequently. And when you fly almost above the gaping hole, it screams like mad.

"But what were to do – not fly? We realized that we risked exposure to doses of radiation, but no-one thought that they must run away. I stayed there for two hours and flew away but my deputies took turns working there for several months. And every two weeks we rotated them. There were arguments. When it was time to recall them, they would shout: 'Why? We're not dead yet, are we?' But we stood our ground. These were medical recommendations, and we brought people back immediately.

"Afterwards, we were accused that we had forced people to go there. No, on the contrary. It was a problem how to fight off people. On my desk I had a thousand applications from volunteers saying, `could you send me.' People realized that there had been an accident and it was necessary to help."

'No one shared information with us'

"We paved the way to a completely unknown world. In 1979 the Americans had a similar accident at Three Mile Island, but they classified all information. No one shared any information with us, and we knew nothing. We were only criticized. It was the Cold War. And no one provided any help.

"On May 1, at a commission meeting, it was already known that there wasn't enough iodine to give to children to protect their thyroid glands, and that there were no cranes with a jib long enough and with enough capacity to place a protective sarcophagus over the reactor. That day, I signed a decree for state funding for equipment and food to the tune of over $120 million - to save the situation. Afterwards, we shared all the experience we had accumulated.

Decontamination of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant buildings. / Photo: Igor Kostin/RIA Novosti

Decontamination of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant buildings. / Photo: Igor Kostin/RIA Novosti

"By the time of the CPSU trial I was already used to being blamed for the tragedy. I was invited to the trial as a witness, and I stood on the rostrum for seven hours. Despite the fact that two and a half months earlier I had survived a heart attack, no one even offered me a chair.

"One of the prosecutors had a pile of papers with all 42 protocols that I had signed, with numerous bookmarks. For a long time, he asked me questions like: 'Comrade Ryzhkov, here we have a protocol signed by you that says in such-and-such a village the recorded level of radiation was that many rems.

"And we have other data…' I was patient but then I snapped. 'How can I, the prime minister of a country with a population of many millions, know how many rems of radiation there were in some remote village? I did not have to know such minutiae at all. I made other decisions. And where were you at the time of the tragedy? Why didn't you, as a Communist, join us like all officers and soldiers, why didn't you apply? What right do you have to ask me these questions?' Well, he went quiet, and asked no more such questions. I still believe that everything was done correctly at the time."

Read more: Poisoned land: 30 years after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox