Top-secret for decades: 3 of the most beguiling Soviet-era mysteries

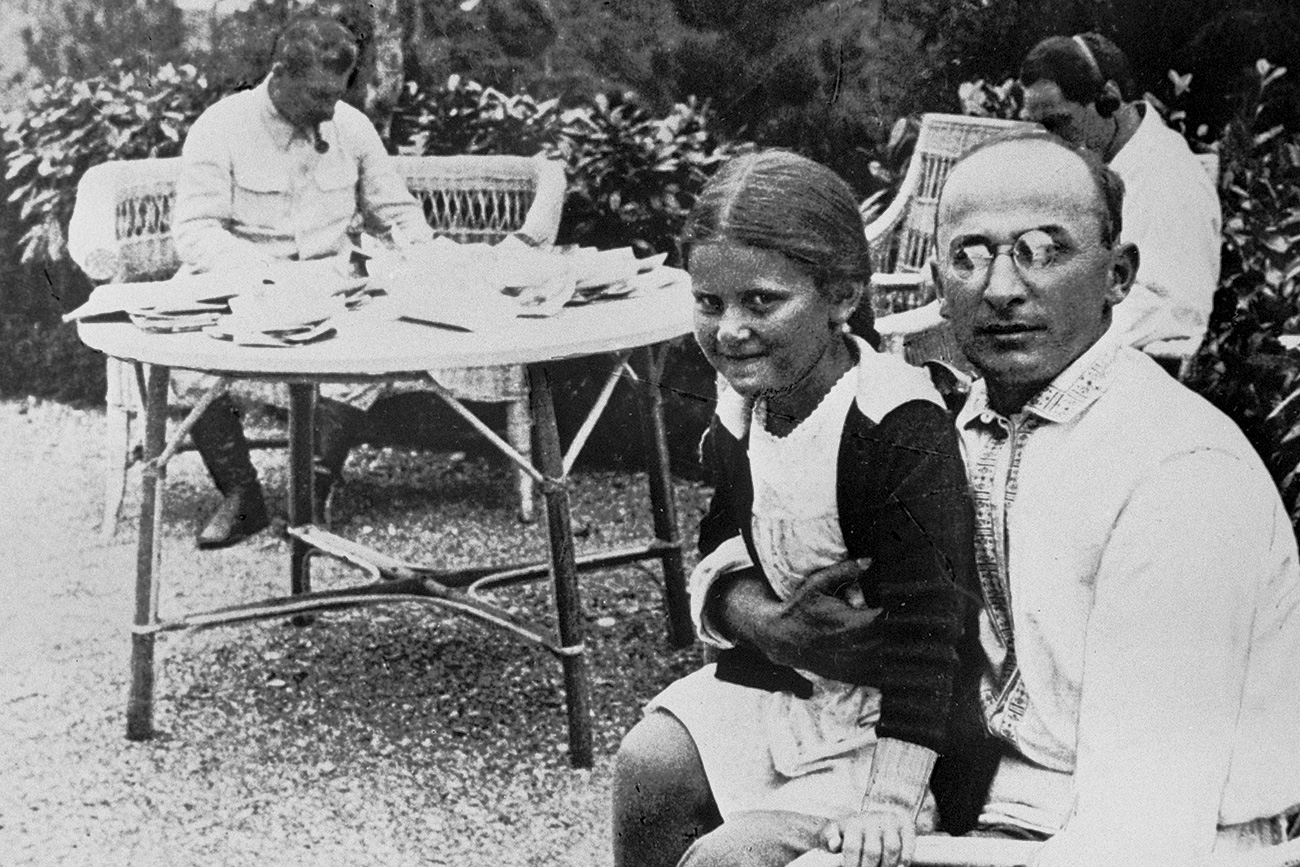

USSR People's Commissar of the Interior Lavrenty Beria with Joseph Stalin's daughter Svetlana.

RIA NovostiAccording to the laws of the Russian Federation, information in state archives can remain classified for no longer than 30 years. However, as the historian Sergei Kudryashov put it in his interview with Radio Echo Moscow, there is no punishment for withholding declassified data, and so several governmental agencies prefer to keep their archives closed.

The Federal Security Service (FSB) - the successor of the Soviet Union’s OGPU, NKVD and KGB is no exception. There still are many secrets connected with the activities of Soviet intelligence, and the state is in no rush to reveal them. Here are some of the most interesting cases.

The fate of Raoul Wallenberg

Raoul Wallenberg while serving as Sweden's special envoy in Budapest, Hungary, in 1944. / Getty Images

Raoul Wallenberg while serving as Sweden's special envoy in Budapest, Hungary, in 1944. / Getty Images

Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg worked in Hungary in 1944-1945 during the final years of World War II. Eager to save as many lives as possible, Wallenberg provided people of Jewish origin with Swedish passports and sheltered the refugees in houses rented by the embassy. His actions saved thousands from death, and so today Wallenberg is one of the most well-known Righteous among the Nations.

His tragic encounter with Soviet agents happened in early 1945, during the siege of Budapest by Soviet forces. Wallenberg visited Marshal Rodion Malinovsky, the head of the offensive against Budapest and was arrested by officials of the SMERSH counter-intelligence organization and charged with spying. That was the last time he was seen alive.

In 1957, Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko handed the Swedish Ambassador a document stating that Wallenberg, who allegedly had been held in Lubyanka prison in Moscow, died in 1947 of a heart attack. It was the first time the Soviet Union recognized that Wallenberg met his end in Moscow, but the reasons remain unclear even today. According to official sources, the interrogation records disappeared.

Many people doubted that the document provided by Gromyko was genuine; there had been many “witnesses” claiming that Wallenberg was still alive in the 1950s, and was living in a Soviet concentration camp or even managed to escape. Only in 2016 Wallenberg was officially declared dead by the government of Sweden. On July 26, Wallenberg’s family filed a lawsuit against Russia's FSB, demanding access to documents related to his death.

Beria’s death

Lavrenty Beria. / AP

Lavrenty Beria. / AP

Lavrentiy Beria, the NKVD chief from 1938 to 1945 and curator of the Soviet nuclear program, hardly has anything in common with Raoul Wallenberg, except for the fact that Soviet secret services were involved in both their deaths. After Stalin’s demise in 1953, Beria, who was infamous for his intrigues and masterminding bloody repressions, lost out in a power struggle with other Soviet leaders (Georgy Malenkov and the future ruler Nikita Khrushchev). This meant the end not only of his career but his life as well.

Accused of spying for the United Kingdom and the falsification of numerous criminal cases, Beria was sentenced to death on Dec. 23, 1953 and executed on the same day – at least, this is the official version. However, some historians believe there was no trial at all and that the once all-powerful secret police chief was shot on the day of his arrest (July 26, 1953) and that his rivals fabricated the whole case in order to present their actions as legal.

This version, depicted in the 2014 film, Lavrentiy Beria. Liquidation, is based on the fact that Khrushchev, Malenkov and other Soviet leaders who had Beria arrested, each described the events differently. Also, nobody ever mentioned where exactly Beria was executed and buried. The death of one of Stalin’s most notorious henchmen remains a mystery, and even if his former colleagues from the Soviet secret services knew the truth, they’d never reveal it.

Chekists and mysticism

Gleb Bokii. / Archive Photo

Gleb Bokii. / Archive Photo

Unlike Hitler’s secret services, which had several units dealing exclusively with paranormal activities (Ahnenerbe), Soviet intelligence was predominantly skeptical about mysticism; believing in the supernatural was considered senseless and, worse, anti-Marxist. On the other hand, there were some exceptions.

One of them was Gleb Bokii, an agent of the Cheka-OGPU (these are different names for the same Soviet secret police) from 1921 through 1934. Not only was Bokii a founder of the Soviet concentration camps system, he also was interested in paranormal activities and communicated with mystics within the special OGPU department that he headed.

Together with occultist Alexander Barchenko, Bokii even tried to organize a Soviet expedition to Tibet in search of the legendary country, Shambhala. However, the government declared such an expedition a waste of time and money, and the project was canceled. Both Bokii and Barchenko were executed in the Great Purge of the late 1930s.

Since that time, the NKVD, KGB and other Soviet secret services deny any involvement in the paranormal. However, in Russia, just like elsewhere, those who believe in the supernatural are sure that there are closed archives filled with information on aliens, ancient mysteries and other signs of supernatural life.

Read more: Why were so many Russians once communists?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox