Rouslan Krechetnikov: 'What is missing now is pure curiosity-driven research'

Source: The Regents of the University of California

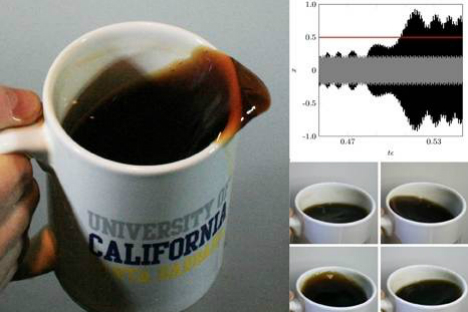

Mechanical engineering professor Rouslan Krechetnikov is known for, as he puts it, “studying the dynamics of liquid-sloshing to learn what happens when a person walks while carrying a cup of coffee."

The research in this area brought him an Ig Nobel Prize in 2012. The Ig Nobel Prize is a play-on-words of the original accolade awarded for improbable research that, "honor(s) achievements that first make people laugh, and then make them think."

He is now an Associate Professor and an Adjunct Professor at both the University of Alberta in Canada and the University of California at Santa Barbara in the U.S. In April 2014 Krechetnikov received the Presidential Early Career Awards for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) from President Obama for his work in the Unites States.

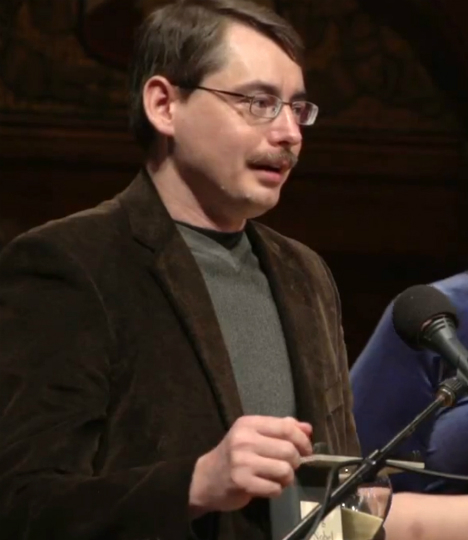

Rouslan Krechetnikov at Ig Nobel. Source: The Regents of the University of California

Rouslan Krechetnikov is an Associate Professor in the Department of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences and an Adjunct Professor in the Departments of Mechanical Engineering at both the University of Alberta in Canada and the University of California, Santa Barbara. Dr. Krechetnikov earned his Ph.D. degree in Applied Mathematics at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (Phystech) in 2004. His work has been recognized with a number of honors and awards, including the NSF CAREER (2011), DARPA Young Faculty Award (2011), Ig Nobel (2012) and the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (2014).

RBTH: What was the impact of the Ig Nobel Prize on your career?

Rouslan Krechetnikov: Some of my colleagues were either skeptical or worried that this may reflect negatively on my career, but great minds like David Gross, a Nobel Laureate in Physics, and Bud Homsy, a member of the U.S. National Academy of Engineering, said I should be proud of it. I think the Ig Nobel Prize is a great way to bring science to the public and fill the knowledge gap between scientists and a wider audience. And, indeed, it did not hurt my career as this year I received the PECASE award.

RBTH: What are you working on now?

R.K.: I now split my time between the U.S. and Canada. Coincidentally, I am working on a project related to water landing; a lot of the fundamental work was done in Russia. In general, I choose problems that have applications in the mind, but also contain interesting, but not well-understood physics questions and thus require deeper fundamental insights.

RBTH: Why did you leave Russia?

R.K.: By the time I was finishing my studies in Russia, society was harmed by severe corrosion due to overturned values and corruption. As a result education and science were deteriorating rapidly. Many talented young people were either leaving the country or taking jobs not to related to science to support their families. It was sad to see that it took no time at all to destroy a great system of education and one of the world’s leading research systems that took decades to build. I did not see any prospects as the country was just selling natural resources and not investing in education, science and technology systematically. Exceptions such as pouring money into a particular area - say, nanotech - are like trying to find a fingernail in a dying body. I wanted to stay in science and support relatives in Siberia so I had to move.

RBTH: Was it difficult to start a new life abroad?

R.K.: On a professional level the first three years in the U.S. were a bit of a struggle to keep up the same level of academic work until I met Bud Homsy from the University of California and then later Jerry Marsden from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Working with them enriched me as a scholar and as a person and helped me to build an independent research career. Having said that, the first three years were not a waste since I continued working on my Ph.D. and then returned to Russia to defend it at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (Phystech).

On a personal level, I have met great people in every country I have lived in and got exposed to various cultural differences that shape one’s personality. While I am proud of my Russian origins, I do not know why cannot I think of myself as also American, European or Asian, for that matter, since I grew up on the east side of the Ural mountains.

RBTH: What do you consider to be your main advantage?

R.K.: I think I have the capability to identify problems where, because of ingrained opinions, other people do not see any problem and basic premises have not been questioned. This is how I often pick up ideas. In this sense, I do not have favorites among the projects I work on. Beyond fluid mechanics, I am proud of my joint work with Jerry Marsden from Caltech on a unified theory of dissipation-induced instabilities. What is missing in science now is pure curiosity-driven research and vision that has been behind all great discoveries and inventions. On the bright side, I believe that nothing can kill natural curiosity.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox