Ancient genetic mutation helps Russians resist AIDS

"People who carry two copies of the mutant CCR5-∆32 gene - one from each parent - are completely resistant to HIV infection, no matter how often they are exposed."

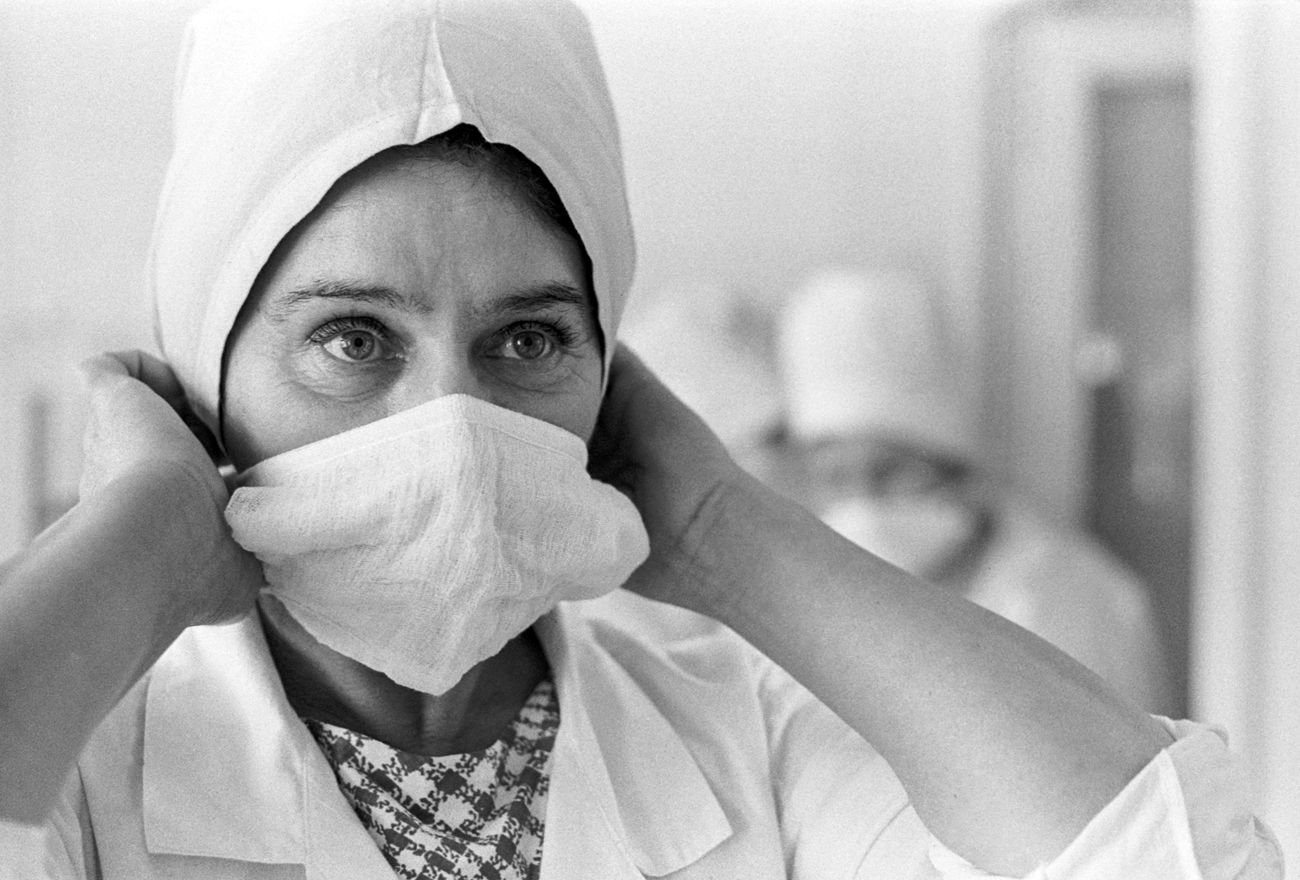

Berti HANNA/Global Look PressRussians are not the only people who carry the HIV-resistant gene, CCR5-∆32, which protects those who carry it. In France, England and Germany, about 10 percent of the population boasts this mutation; and the figure in Italy, Turkey and Bulgaria is about 5 percent. In Saudi Arabia, China and Africa, however, no one enjoys this protection. Of significant interest is that in studies of African-Americans with some European ancestors about 2 – 5 percent are HIV-resistant.

Project history

The Genome Russia Project led by St. Petersburg University began in 2014. Since then, scientists received 1,500 samples of genetic material from ethnic Russians and minority national groups in the country. During this period, nearly 50 genomes of Russian citizens were studied and deciphered.

"We did not expect that we’d find anything unusual in the Russian genome, and we just wanted Russia to join the world genome research community," said Stephen O'Brien, a professor at St. Petersburg University, head of the Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, and head of the Genome Russia Project. "Today, we’re looking for biomaterials throughout the country, collaborating with Russian scientists and regional governments."

The study of Russian genomes will help trace the history of migration and native ethnic groups in Russia, starting from the Neolithic Age. In addition, genome data will be used for personalized medicine in the near future.

HIV resistance: how does it work?

Resistance to HIV infection is found in people with a mutated CCR5 gene. In general, the CCR5 gene has proteins that are needed for HIV to penetrated T-lymphocytes, the cells that HIV infects. CCR5 is the only gateway into the human body for the virus, and people who carry two copies of the mutant CCR5-∆32 gene - one from each parent - are completely resistant to HIV infection, no matter how often they are exposed.

The CCR5-∆32 gene mutation is hereditary and has various degrees of effectiveness against HIV. People who inherited a single copy of CCR5-∆32 from one parent can be infected with HIV, but their bodies will better deal with it and slow its rate of progression by as much as 12 years.

At the same time, half of CCR5-∆32 carriers that are HIV infected do not develop lymphoma, a common secondary disease seen in AIDS infections. Those who inherited CCR5-∆32 from both parents are completely resistant to HIV infection and AIDS.

Professor O'Brien said that the gene mutation appeared about 5,000 years ago, which was about 60,000 years after Europeans migrated and broke away from mankind’s African and Asian ancestors. That’s why CCR5-∆32 is today found only in European Caucasian ethnicities, but not in native East Asian or African peoples. Scientists say that every fifth inhabitant of Europe and Russia carries at least one copy of CCR5-∆32.

Search for the resistant gene

Professor O'Brien’s search for gene resistance started in the early 1980s at the U.S. National Institute of Health, where he gathered blood samples from some of the earliest reported AIDS patients.

Before a blood-screening test for HIV was developed, nearly 12,000 Americans received donated blood from those infected with HIV. Oddly enough, only 85 percent became infected, and the remaining healthy 15 percent piqued the interest of scientists. In addition, they were mystified why in some people HIV became full-fledged AIDS after just a year, but for others it took 20 years.

O'Brien's research team suspected that genetic differences among people might influence their susceptibility or resistance to HIV. After his team discovered CCR5-∆32, they continued research and by the late 1990s they had uncovered over 20 natural mutations that prevent HIV. Approximately 10 percent of people who avoided infection after exposure had the CCR5 mutated gene, and the remainder had other genetic guardian genes that protected them

Can one acquire the mutant gene?

The good news is that thanks to modern gene transfer technologies, genetic resistance to HIV can now be engineered. In 2007, Timothy Leigh Brown, an American with AIDS and leukemia living in Berlin, received a stem cell transplant from a bone marrow donor who carried two copies of CCR5-∆32.

Brown’s own lymphoid system was destroyed by irradiation before the transplant, and his treatment with anti-retroviral therapy was stopped so as to not interfere with the growth of the donor stem cells. His HIV infection has not returned, seven years after the transplant. Brown boasts the distinction of the only person to be cured of AIDS and HIV.

Today, a cutting-edge experimental treatment of end-stage AIDS involves a "knock out" of the CCR5 gene in a patient’s own lymphocytes. This is a promising, albeit expensive, therapy for the disease, and tresults are promising so far.

Read more: Can the Siberian fir cure cancer and slow down aging?>>>

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox