How a Soviet auto giant became a ghost factory

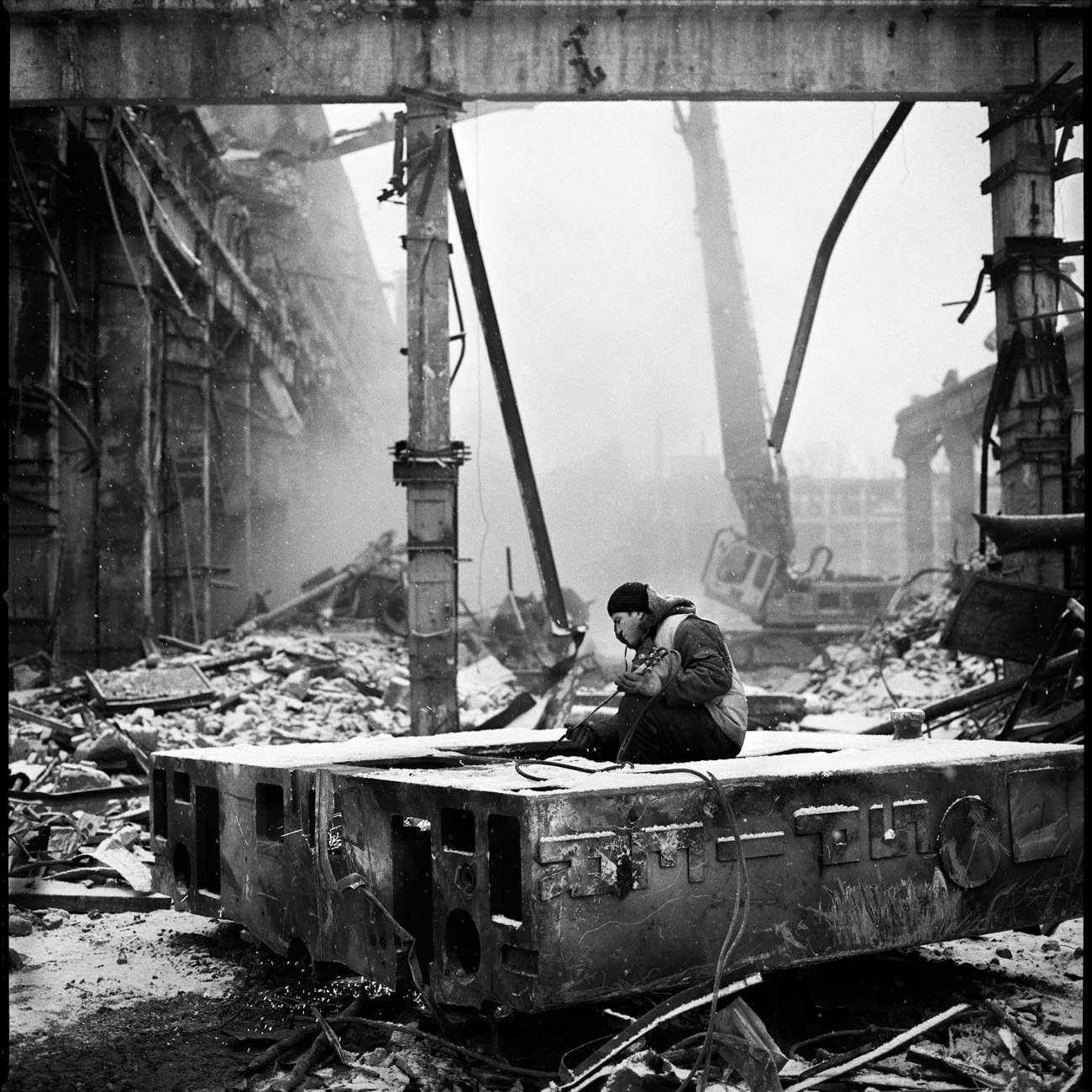

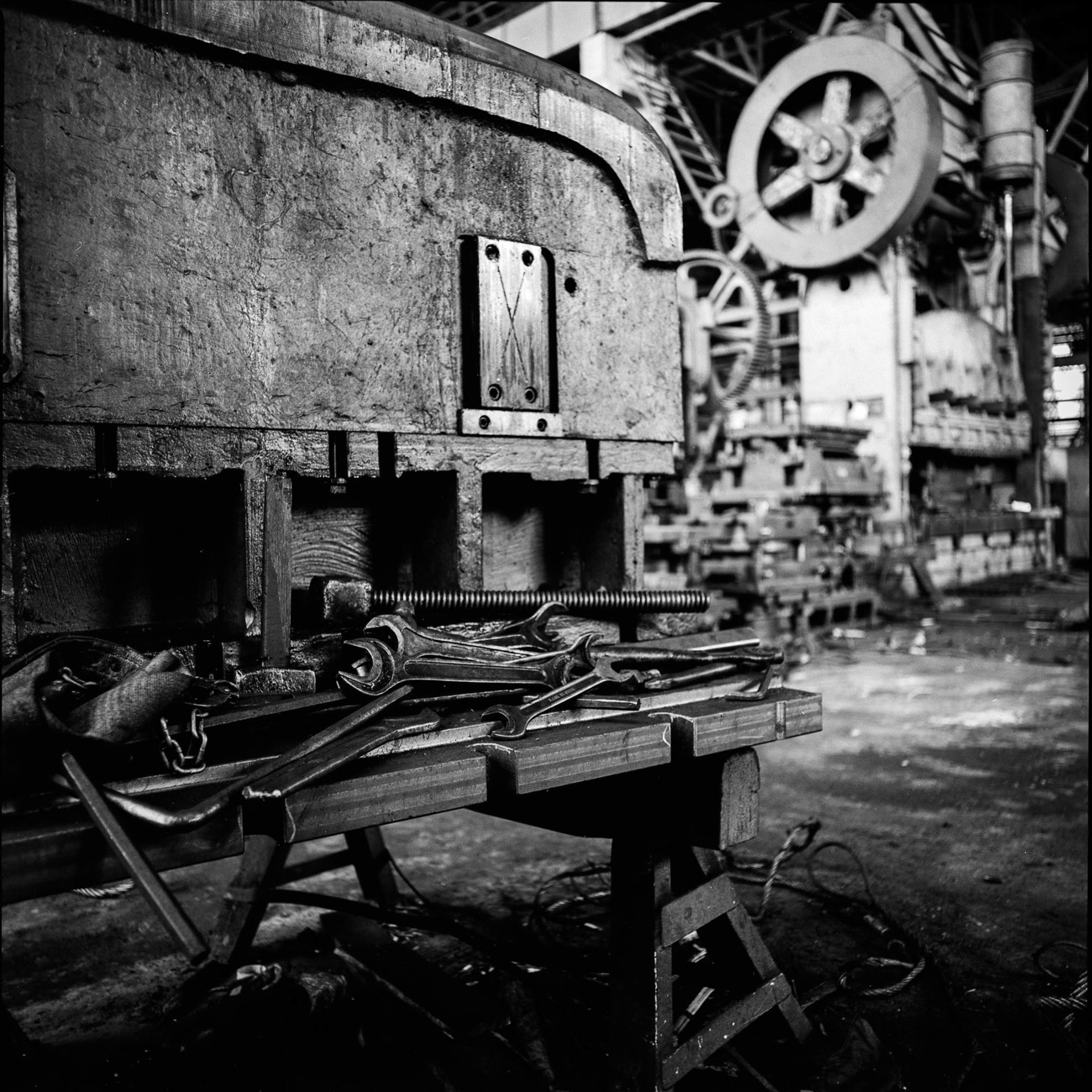

Today the plant’s workshops have been dismantled, and the only mementos of its past glory are photographs.

Stoyan Vassev

In Soviet times, the Likhachev Plant (Zavod Imeni Likhacheva, ZIL) made not only legendary trucks, but also limousines for the country’s top officials, army off-roaders, and even bicycles and refrigerators.

Stoyan Vassev

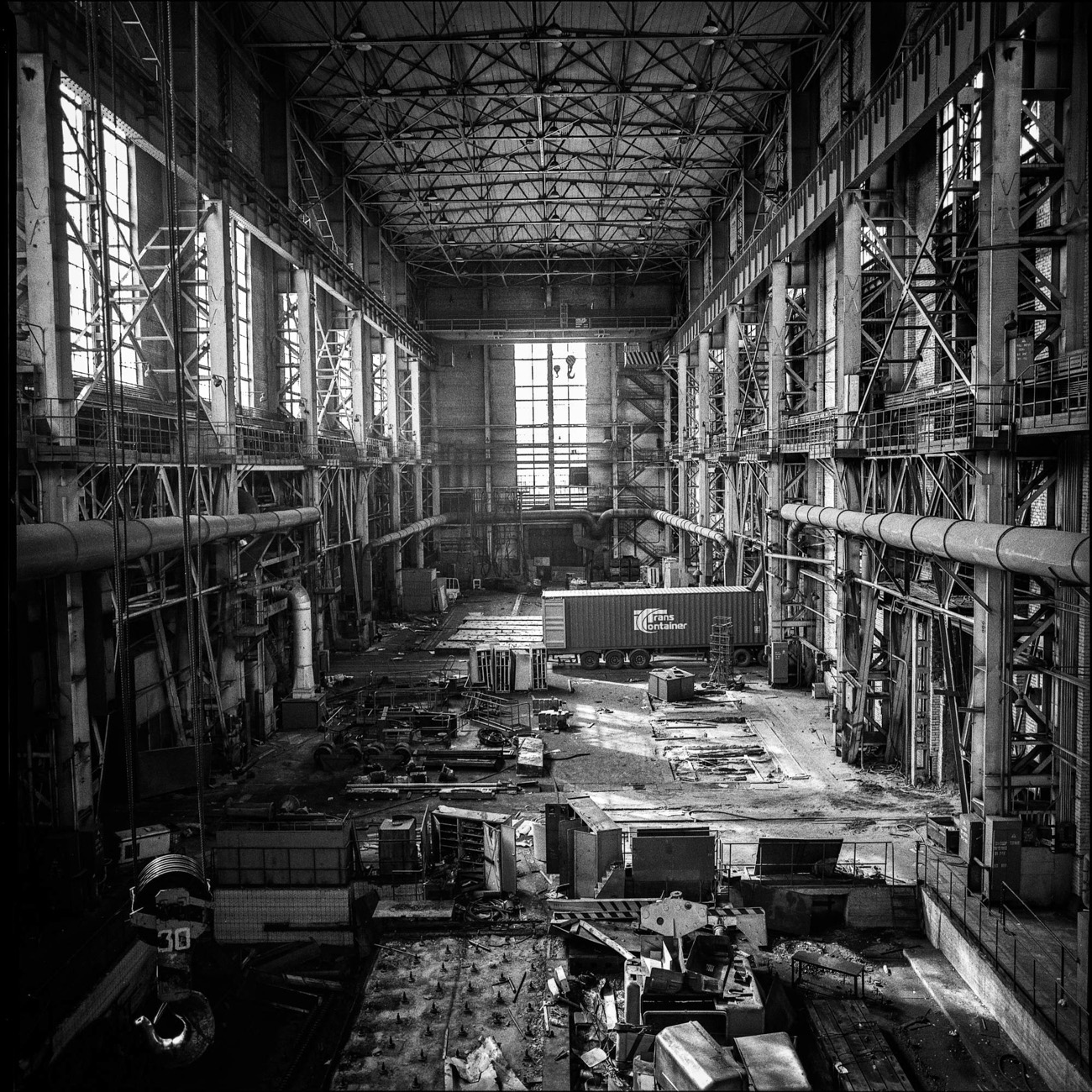

Moscow’s largest industrial zone covered an area of around 300 hectares.

Stoyan Vassev

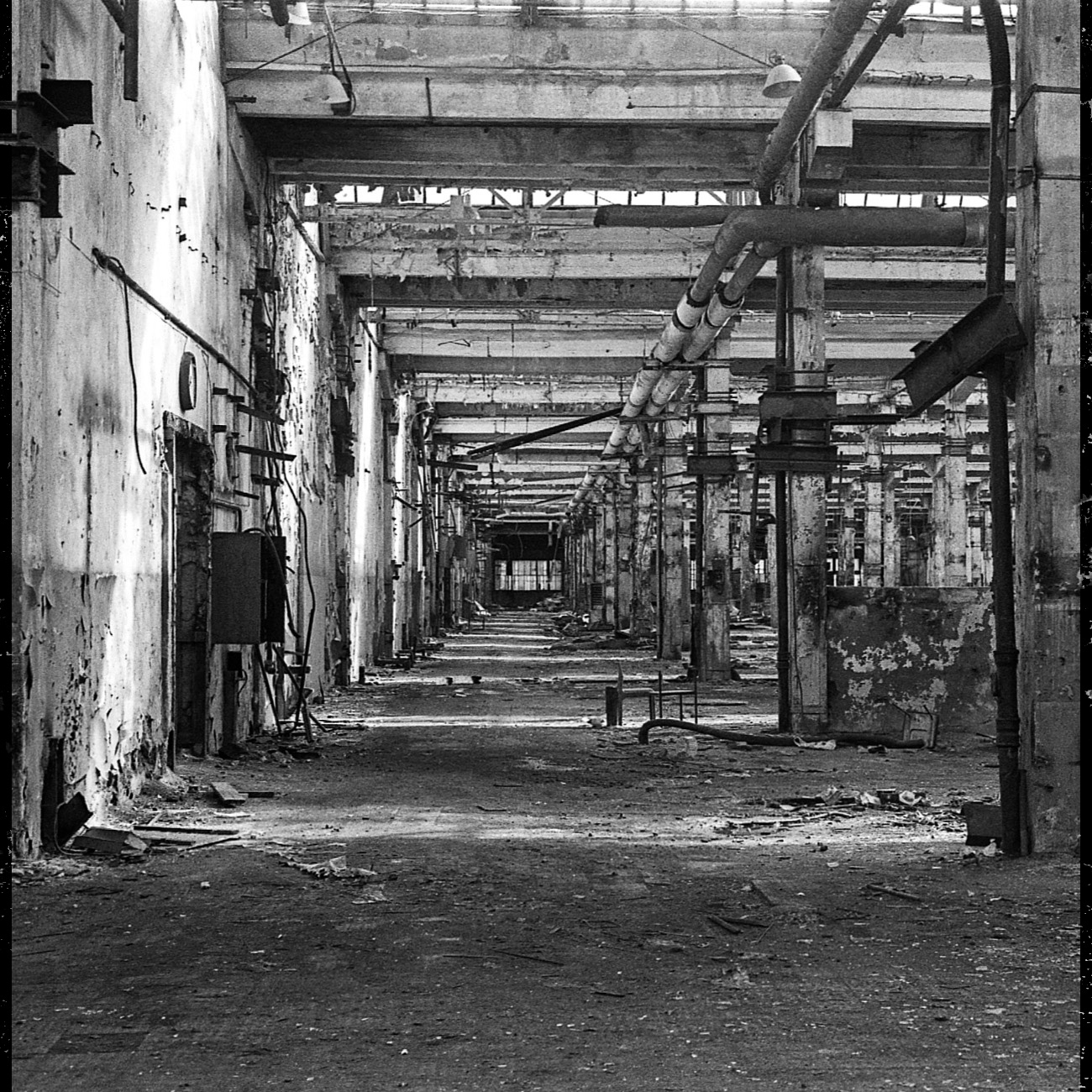

This industrial monument not far from the center of the Russian capital today looks like ready-made scenery for either a video game or a post-apocalypse movie.

Stoyan Vassev

The plant’s first production unit was set up in 1916. Back then it was called AMO (Moscow automobile society) and was the first Soviet plant to produce trucks. Known as AMO F-15, the model was actually a copy of the Italian truck FIAT 15. In the 1930s the factory was named after Stalin.

Stoyan Vassev

During the Great Patriotic War, the factory made mortars and grenades that went straight from the conveyor belt to the front line. The ZIS-6 truck, on which the famous Katyusha rocket launcher was mounted, rolled all the way to the walls of the Reichstag. During the war years, the ZIS auto plant produced around 100,000 trucks and ambulances in total. In June 1942, the plant was awarded the Order of Lenin for arms supply excellence, which was followed up in October 1944 by the Order of the Red Banner of Labor.

Stoyan Vassev

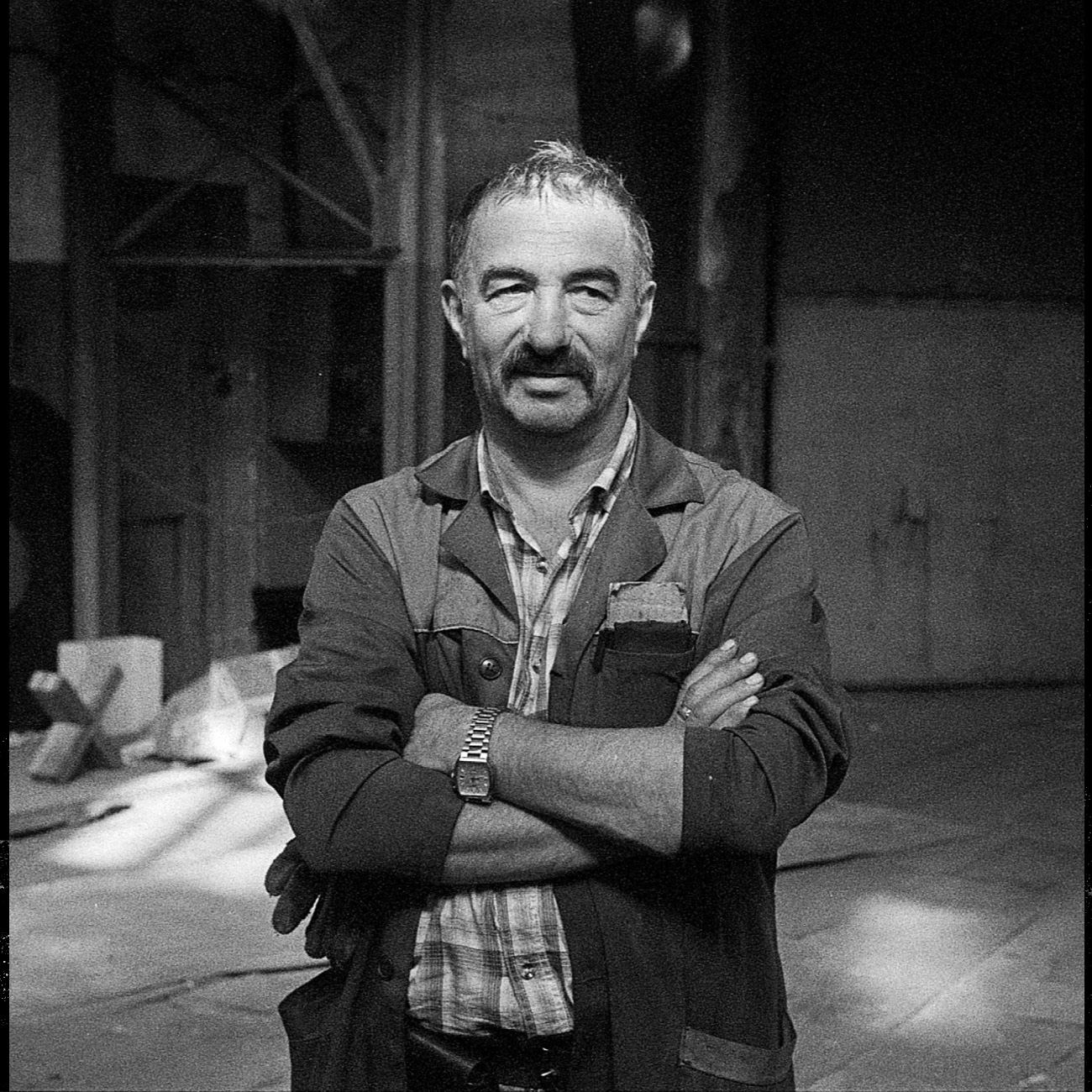

The factory used to employ 65,000 people, with entire working dynasties. Vladimir Ivanovich worked here more than 40 years. He serviced elevators and all the conveyor lines.

Stoyan Vassev

An abandoned ZIL 130 awaits its turn for the scrap heap. Back in 1963, it was one of the most modern trucks of its time. It was even given the USSR mark of quality.

Stoyan Vassev

ZIL is a city inside a city. It’s estimated it would take at least a year to walk round all the production units.

Stoyan Vassev

In Soviet times, the factory had its own gasoline pump. The ZIL plant bears plenty of Soviet-era traces to this day.

Stoyan Vassev

In the late 1950s, the plant was named after its director, Ivan Likhachev. During its long existence, ZIL assisted other enterprises. For example, the ZIL-170, engineered in the late 1960s, formed the basis of the first vehicles produced by the KAMAZ plant.

Stoyan Vassev

The motor production unit gave birth to the heart of the vehicle — the engine, consisting of hundreds of parts on a semi-automated line. In total, the vehicle assembly process involved about 70 operations.

Stoyan Vassev

Inessa Storozhenko joined the plant in 1962. The photo she is holding depicts writer Maxim Gorky, her father Miron Klitskin and plant director Ivan Likhachev. “Likhachev was the deputy head of the party district committee. Later he became Stalin’s pet,” she recalls. “He was very foulmouthed at times.”

Stoyan Vassev

The ZIL garage. 1936 saw the start of production of the first Soviet limousine, the ZIS 101, based on the U.S. Buick. Instead of buying the blueprints, it was reverse-engineered from a finished model. In September 1942, Stalin ordered the development of a new luxury-class limousine, the ZIS 110, this time based on the Packard. The “wild 90s” that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union caught ZIL unprepared. The head of state switched to a Mercedes. Domestic limousines were out of favor.

Stoyan Vassev

In 1992, the plant developed the 53-01 “Bull” truck, based on a Mercedes model. It formed the basis for a series of minibuses. Until 1994, the factory still produced the ZIL 130 truck. However, it was unable to compete with the latest foreign models. In the late 1990s, the factory was hit by cheaper Chinese models, and the threat of closure loomed large.

Stoyan Vassev

Vera Avsineeva came to the plant in 1972 to work as a conveyor operator. “The job was held in high esteem. It was always hard, but interesting work, operating the programmer and controllers, for example. There was always a lot to learn,” she says. “The plant operated 24/7.”

Stoyan Vassev

By 2000, ZIL was in a critical condition. The Moscow authorities took the decision to build a technopark and a residential area on the factory site. The plant officially ceased to exist in 2013, and most of the buildings were dismantled in 2015. Now the former factory site is being actively built up. It will be replaced by a residential quarter and a technopark.

Stoyan VassevSubscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox