Russians remember how they felt the day Stalin died

Russia marks the 60th anniversary of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s death. Source: RBTH / Ricardo Marquina

The death of Joseph Stalin on March 5 shocked the Soviet nation. His body was put on display in the Hall of Columns of the House of Unions in the centre of Moscow and hundreds of thousands of weeping mourners came to say goodbye to their leader. The first day of mourning resulted in a tragedy as a crush on Trubnaya Square resulted in the deaths of dozens, maybe even hundreds, of people – even now, no one knows for sure how many people died that day.

For many, Stalin’s death was akin to the assassination 10 years later of U.S. President John F. Kennedy – Russians old enough to remember that time know exactly where they were when they heard the news.

Semyon Kvasha and Vladimir Yerkovich of RBTH spoke to some of them about their memories of that day.

Dalila Avanesova, 73:

|

| Dalila Avanesova. Source: Archive photo |

I remember the day Stalin died. They got us all together in school and lined us up in the corridor to mourn. Funeral music was playing. I remember the guards of honor of the pioneers and the Komsomol [Soviet youth movements] standing next to Stalin’s bust.

They stood to attention and saluted. Everyone was crying – the pupils, the teachers. But I wasn’t. I was confused by everything that was going on. Lessons had been cancelled and everyone went home to mourn.

When I got home, I could sense this kind of hidden joy. Maybe it was just me, but I could see the delight, the joy, the glitter in my mom’s eyes. There was a lightness to her every movement; she was full of energy, full of happiness, like a crushing weight had been lifted from her soul. She was my grandmother, but I called her “mom” because she had raised my brother and me. Her son – my uncle – was the writer Yury Dombrovsky.

He had faced political repression and was in exile at the time.

But she didn’t tell us about that. What could you tell children during that time? I had a friend at school called Valya Neskuchayeva. Her parents said she couldn’t hang around with me. “My mom and dad say I can’t be friends with you,” she said, “because your family’s politically unreliable.” I was really surprised by that phrase – I didn’t even know what it meant.

Alexandra Grigoryeva, 78:

|

| Alexandra Grigoryeva. Source: Archive photo |

I was in my fourth year in college at the time in Baley, which is in the Zabaikalsk territory. I remember that we had to memorize a bunch of Stalin quotations as part of our coursework for that year. They were very strict about that. We were in class when there was a knock at the door and the teacher went out of the room.

When she came back, she seemed out of sorts. She sat down at her desk, held her face in her hands and started to cry. A moment later she raised her head and said, “Joseph Stalin is dead.” We all cried. Everyone cried – our group comprised mainly girls and there were only three boys in our class and they cried too.

I shared a room with two friends – we rented it from this guy. He was an old communist and had worked all his life in a gold mine. We got home from classes to find him sat on the bench in front of the house sobbing away, “Why Komsomol, why? How the hell are we supposed to go on now? Our father’s dead.” We really didn’t have any idea how to live without Stalin.

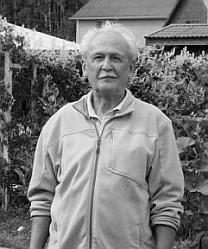

Viktor Yerkovich, 74:

|

| Viktor Yerkovich. Source: Archive photo |

I was living in a worker’s village not far from Nizhneudinsk in Irkutsk region at the time, a pupil in the eighth grade. I remember the whole village was in tears, quite literally. And they weren’t just crying – they were bawling their eyes out. They couldn’t keep it in and cried openly and honestly.

It seemed that that was it, that life couldn’t go on. For us, members of the Komsomol, it was a bigger tragedy than the Great Patriotic War.

I remember lying on the floor in the classroom; I knew I should be crying, but I couldn’t. And I wasn’t worried that someone would see me and think that something was wrong with me. What bothered me was the very fact that I wasn’t crying – that was what was strange. So I started to wipe the spit from my mouth on my face to make it look like I’d been weeping.

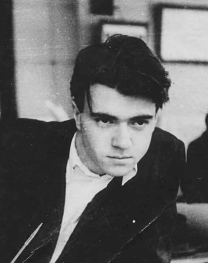

Felix Kvasha, 79:

|

| Felix Kvasha. Source: Archive photo |

I was in my second year at university at the time, living in halls of residence in the Moscow suburb of Sheremetyevo. The dorms were really big; they could fit about 20 people, like army barracks.

They announced Stalin’s death over the radio the evening he died. Everyone wept. We were all in a state of shock – the world had just come to an end. But I didn’t cry; I didn’t tear my hair out.

They cut classes short the next day to take us to the House of Unions and pay our last respects. We formed a massive line of about 500 people. We were told to stay in line and not veer off course. After waiting around on the university grounds for about two hours, we finally set off.

It was a rather leisurely affair to begin with; no one was in a hurry, we took breaks and had roll calls. It was already evening by the time we got to Trubnaya Street.

The place was jam-packed with thousands of people. Our formation had already disintegrated by then. Some people had probably escaped home; everyone else had coalesced into the crowd. There were perhaps five or six faces that I recognized. Everything else was just one long, never-ending mass of people – unfamiliar faces turned somewhat barbaric by the conditions.

The boulevard was lined with trucks with soldiers standing behind them. And that was what made the whole situation so terrifying. The crowd stood there all night and didn’t move. You’d just get to know the person next to you before that person would disappear somewhere. Some people tried to crawl out under the trucks, but the soldiers pushed them back.

Others tried to get through the cabs – I don’t think they made it. It was worse for those who were squashed up against a truck. We stood there all night. We didn’t have anything to eat or drink, and we couldn’t go to the bathroom either. The courtyards in between the houses were out of bounds, as were building entranceways.

After some time, I found myself about 300 feet away from Trubnaya Square. Some guys were there, about 16 or 17 years old. We were all squashed up quite closely together and I could hear them talking about how to get out. “Maybe we should take to the roofs?”

And it was those boys who saved my life. They found a building entrance that hadn’t been properly secured and pulled me into it. We went through a courtyard that acted as a kind of through passage, and then another. Then we climbed onto a roof. That’s when I lost them. I jumped off the roof and found myself on Tsvetnoi Bulvar, which runs parallel to Trubnaya. I was completely shattered, but alive.

Valentina Shishkina, 72:

|

| Valentina Shishkina. Source:Archive Photo |

We were home listening to the radio when we heard the news of Stalin’s death. Everyone cried – my mum, my sister and I. Our leader, the person everyone loved more than their own mother and father – our god – had died. I went to school the next day. We gathered together to mourn Stalin's death, and everyone sobbed there too.

My elder sister Tamara went to see the body with her friend. My mom had forbidden her to go; she had slammed the door dramatically when they had been discussing it. But they went anyway. They walked from Leningradskoye Shosse, which was on the outskirts of Moscow back then, all the way to Pushkinskaya Square in the center of the city.

That’s a good three or four miles. They walked because the trams were not running that day. It was on Pushkinskaya that the crush began. They were being pushed from behind and got scared. They crawled under a car and slipped out into a side street. The soldiers that were standing there let them through, evidently because the girls were absolutely terrified. They went home the same way they had come.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox