The ultimate sentence: Where do Russians stand on capital punishment?

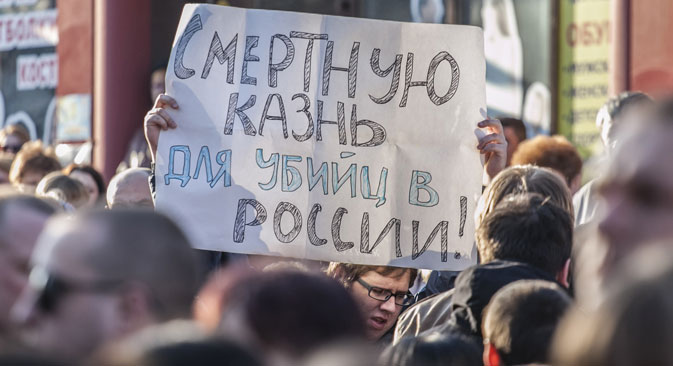

A Belgorod resident holds up a poster demanding capital punishment for those guilty of murder, at the site of a shooting incident on Narodny Bulvar in Belgorod. Six people were killed in the incident. Source: Alexandr Urivskiy / RIA Novosti

In recent years in Russia, proposals have periodically been heard to cancel the moratorium on the death penalty. These calls have been voiced especially by a number of MPs who urge capital punishment for pedophiles. Just recently, the head of the Russian Investigations Committee, Alexander Bastrykin, spoke of "a hypothetical possibility of using" capital punishment.

Russia has a long and far from edifying relationship with capital punishment, a history that reached its grim apogee with the executions of hundreds of thousands during the Stalinist era, many on absurd trumped-up charges.

Yet paradoxically, the country was also one of the first to effectively abolish the practice 270 years ago, though the ban was not to last. But what do Russians think about the death penalty in this day and age, in a time in which capital punishment is illegal?

Listening to the people

On the whole, Russians are very tolerant of capital punishment. A poll conducted by the Public Opinion Foundation two years ago showed that 62 percent of Russians were in favor of reinstating the death penalty.

Some 72 percent of respondents said that capital punishment should apply to those who commit sexual crimes against minors; 64 percent said that murderers should be eligible; and 54 percent argued that terrorists should pay the ultimate price, while 12 percent advocated the death penalty for treason.

Experts are convinced that the authorities should not be following public sentiment on this issue. Maria Kannabikh, president of the non-commercial organization Interregional Charitable Fund of Assistance to Prisoners, is categorically against the death penalty. "Capital punishment does not make things better, because cruelty always breeds cruelty," she told RBTH.

In an interview for RBTH, head of the For Human Rights movement Lev Ponomaryov said that pro-capital punishment sentiments had been present in society for quite some time, and not only in Russia.

"There is a myth that a tougher punishment can help reduce crime,” said Ponomaryov. “However, international experience shows that it does not solve anything. The UN has conducted research in dozens of countries and its findings confirmed this. However, the abolition of the death penalty makes society more humane," he said.

Ponomaryov pointed out that when people talk of capital punishment, they are governed by personal revenge, saying: What if your child were killed, wouldn't you want the killer to die? "Whereas a country's leaders should be thinking of bringing the number of crimes down, of reducing aggression in society, of possible mistakes and innocent people who may be executed," he concluded.

The only state in Europe that still applies capital punishment is Belarus.

A bit of history

In late May 1744, Her Majesty Yelizaveta Petrovna, daughter of Russian emperor Peter the Great, instructed all state prisons to send detailed reports about inmates sentenced to death to the capital and not to execute them without receiving a royal decree to that effect.

Under the 1744 decree, Russia became the first European state to humanize its penal system, says the Moskovsky Komsomolets daily. Although, formally, that document did not remove the death penalty from the laws, in practice capital punishment was abolished.

And despite the ban, some executions still took place. In the period between 1741 and 1825, seven people were executed, all of them conspirators, including the infamous Cossack insurrectionist Yemelyan Pugachev, though Yelizaveta Petrovna had passed away more than a decade before Pugachev met his end.

Later, Russian emperor Pavel I wrote on the only death penalty verdict passed during his reign: "Thank God, there is no death penalty in Russia and I will not be the one to introduce it."

However, a period of stability in Russian history then came to an end and in the 80 years from 1825, a total of 625 people were sentenced to death, 191 of whom were actually executed.

Early in the 20th century, Russia entered a period of turmoil. In just three years between 1905 and 1908, some 2,200 were executed in order to suppress rebellion. For other crimes, no capital punishment was applied until 1918.

However, from the establishment of Soviet rule in 1917 up to 1947, the number of those who fell victim to the state’s punitive machinery reached horrific proportions. Hundreds of thousands of people were sentenced to death, with historians putting the figure at over 600,000. That is to say, some 1,200 people were executed every day during this period.

On May 26, 1947, Joseph Stalin abolished the death penalty, only to reinstate it in the early 1950s.

Starting from 1962, capital punishment was applied in the USSR for economic crimes as well, for instance for "foreign currency machinations". In the period between 1962 and 1990, some 24,000 people were executed.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, when the country began to move towards democratic values, there was a sharp reduction in the number of executions. In the five years between 1991 and 1996, the figure was 163. The last execution was carried out in Russia on September 2, 1996.

Earlier, on May 16, 1996, Russian President Boris Yeltsin had issued a decree on a gradual reduction in the use of the death penalty in connection with Russia's accession to the Council of Europe.

On April 16, 1997, a moratorium on the death penalty was introduced, and on June 3, 1999, 703 people who had been sentenced to death had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. On November 19, 2009, the Russian Constitutional Court ruled that the death penalty was in violation of Russia's international obligations.

Read more: Jailbirds, artists and entertainers: The story of Moscow’s Alcatraz>>>

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox