Why Russia’s middle class is like no other – according to some

The core of the Russian middle class comprises employees of the state sector. Source: ITAR-TASS

According to a recent report by the Institute of Sociology at the Russian Academy of Sciences, 42 percent of the Russian population is categorized as middle class – an unprecedented statistic for the country. However, the image of the middle class painted by the sociologists greatly differs from international standards.

The core of the Russian middle class comprises employees of the state sector, and on the periphery are entrepreneurs, service sector workers, highly qualified professionals, and employees in various other sectors.

The Russian middle class cannot be labeled “advanced” per se. “In the 1990s, there was only a small group of people with average incomes, and this was rightly considered an advanced social stratum,” said Vladimir Petukhov, director of the Center for Comprehensive Social Research at the Institute of Sociology.

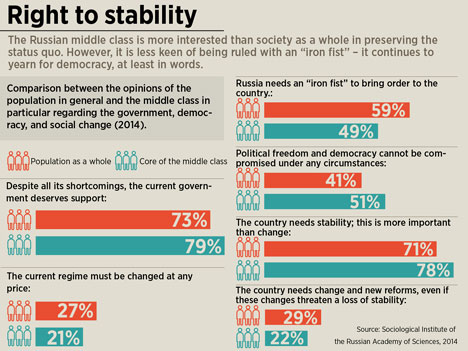

“By 2014, the majority of the middle class was loyalist and strongly sympathized with order and stability. Moving society forward was not at all a priority for this group,” he said.

Therefore, the middle class, which constitutes state servants and similar workers, may not provide for much GDP growth, but it does guarantee constancy in the elections.

“In some sense, our middle class is a mirror of the entire Russian society,” Petukhov said.

Variations of “middle”

The predominance of the public sector, loyalty to authority, and a lack of desire to increase one’s qualifications are bizarre characteristics for a middle class. The Institute of Sociology found just the right time to publish its results, as the expert community had taken notice.

There are always people with higher incomes and people with lower incomes in society, and so it follows that there are people with average incomes. However, no one is saying that these people can necessarily be called middle class.

Statistically, the number of public administration employees grew by more than 20 percent from 2001 to 2011, while the number of individual entrepreneurs dropped by 13 percent in 2013 alone, and currently stands at no more than 3.5 million people. No more than 7 percent of Russians are involved in entrepreneurship.

“Here we have a juggling of concepts,” said Yevgeny Gontmakher, board member at the Institute of Contemporary Development. “The middle class is not so much a material as a socio-cultural phenomenon. We would really like to have one and so we call it whatever we get from some intricate sample or other. Several years ago, we counted some 20 percent of Russians who matched the general understanding of a middle class. We set simple filters: Members of the middle class not only have a normal income – at least $1,000 per capita – but also an apartment, a car, a dacha. They should be mobile, plan their lives independently, and not live dependently, particularly not off the government.”

At the end of last year, the Independent Institute for Social Policy had an even stricter approach to identifying the middle class – it searched for people who, in the 20 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, had found new ways of topping up their household budget in comparison with the Soviet period.

According to its findings, only 2 percent of Russian families earn substantial incomes from property and financial assets, another 5 percent are able to live well as entrepreneurs, and no more than 8 percent had adapted to life in non-Soviet Russia. This last group is the middle class.

The rest – averages in terms of income, education, non-manual labor, and self-identification – were the filters proposed by the Institute of Sociology. But in terms of sources of income and mentality, they were very different.

Rise like a phoenix

“We are dealing with an uprising of the Soviet masses. When the concept of ‘middle class’ was born, we were referring to those who earned a decent living through their own labor, who regularly paid taxes and were capable of free choice – of authority, of a profession, of residence,” said Julius Nisnevich, a political science professor at the Higher School of Economics.

“This group was responsible for up to 70 percent of GDP in developed countries, which meant it influenced politics. It didn’t exist by definition in the USSR, but in the 1990s many people understood that they could become middle class. The Soviet masses wanted to be middle class. We got a ‘middle class,’ which viewed the government as the key instrument of its wellbeing.”

The similarities between the society described by the Institute of Sociology and the Soviet social structure are generally obvious. If we add all employees of state-run corporations to the “state sector” category, the number of people in the middle class goes down.

Paradoxically, by all statistical calculations, it is not profitable to be a civil servant in this country. According to the Center for Labor Market Studies at the Higher School of Economics, a specialist who opts for the public sector over the private sector loses around 20 percent of his wage.

However, there are implicit advantages: benefits, shorter hours, work privileges, stability, etc., all of which puts civil servants in a position no worse than private sector employees.

Click to enlarge the infographics

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox