Translation: A labour of love or a science?

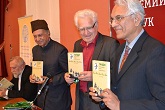

The congress saw the awarding of the Read Russia Prize – the only prize for translation of Russian literature – in four categories. Source: RG

The theme of this year’s congress was “Translation as a Form of Cultural Diplomacy.” This topic reflects both the current turbulent geopolitical environment and the principles that inspired the foundation of the Institute of Translation itself.

Bridging the gap

“We wanted to create a forum where translators from all over the world could exchange bits of wisdom and professional experience on their art form,” said Vladimir Grigoriev, the Deputy Head of the Russian Federal Agency for Press and Mass Communications and one of the Institute’s key founders. “But we also had in mind the higher, more philosophical purpose of translation, which is a means of uniting people from different countries. Although it is highly technical in nature, translation is after all not a science but an art, and there’s a certain degree of cultural alchemy that takes place when you translate, because you’re not just replacing one word with another, you’re creating a palpable bridge between the cultural mentalities of two countries.”

The Congress of Translators was founded by the Institute of Translation in 2010, and the first event attracted over 150 participants from 20 different countries. The second congress, which took place in 2012, boasted translators from 30 different countries.

The congress played host to an incredibly diverse range of lectures over its two days, and there were almost 300 given in total. Each morning and afternoon session consisted of nine separate “sections,” with each section focusing on its own theme that was explored by five or six translators and a moderator.

Topics included practical issues such as “How do you avoid unintentional plagiarism in classic works that have been translated numerous times?” and “How does one translate cultural context?” Many lectures were devoted to language-specific dilemmas like “The difficulties of translating Nabokov and Chekhov into Japanese.” These lectures were a chance for genuine, passionate cultural exchange, as they concerned questions that literary translators frequently encounter.

The congress also touched on pedagogical subjects such as “What is the role of the university in molding young translators?” and “How to teach students to preserve the ‘soul’ of a text,” as well as more ontological questions such as “Does the translator need to know everything?” or “Is translation more of a science or a labour of love?”

Impressions of an intellectual feast

The highlight of the congress’s first day was a lively evening discussion between Russian writers who took to the stage in pairs, with each pair representing opposing points of view on different subjects related to life and art.

The congress also saw the awarding of the Read Russia Prize – the only prize for translation of Russian literature – in four categories. The prize for translation of classic 19th century Russian literature went to Alejandro Ariel Gonzales for his Spanish translation of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Double. In the 20th Century Russian Literature category, the award went to Alexander Nitzberg for his German translation of Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita. Marian Schwartz won the prize in the Contemporary Russian Literature category for her English translation of Leonid Yuzefovich’s Harlequin’s Costume. Finally, the winner in the Poetry category was Liu Wenfei, who translated selected poems by Alexander Pushkin into Chinese.

Indian Connection

India was represented by Russian to Hindi and Marathi translators, as well as Russian to Indian English translators like Girish Munjal. When asked about the nuances of translating from Russian to Indian English, Munjal said, “I would say syntactic structure and phraseologies that only Indians can understand. Sometimes there could even be elements of Hinglish (combination of English and Hindi) because our readers understand this.”

Liu Wenfei, the winner in the Poetry category. Source: RG

Munjal believes the best way to raise awareness of Russian literature among Indian youth was to translating text in a rhymed way and read it aloud to pupils and those unlikely to go to the library. “According to my observations, after our readings schoolchildren show great interest in Russian books,” he said.

Munjal said his centre was preparing Pushkin’s Snowstorm for reading and had already fine Gogol’s Cloak. “We had to make some adaptations there. For instance, the surname of the protagonist, Bashmachkin, is perfectly understandable for us, Russian-speakers. But for Indians who can’t speak Russian this is not clear, so we played with words and translated the main character’s surname in such a way that it made sense to Indians. Some allowances are possible because even a very good, 100 percent accurate translation sometimes is not read because it is not clear for the readers or listeners,” he said.

Megha Pansare, a Russian to Marathi translator frets the fact that translators in India are often not paid for their hard work. “I believe a common platform should be created for Indian translators and Russian writers as well as publishing houses to get together and discuss this question,” she said. Pansare believes there is a definite lack of support, promotion and awareness of the Russian literature in India at the moment, but added that Zakhar Prilepin, Andrei Volos, Boris Akunin are quite popular among Indian readers.

She said several magazines were interested in publishing stories written by contemporary Russian writers in special issues. “A lot of people read those issues and they familiarize themselves with the new literary works. But this is not enough. I believe that we should publish books containing collections of stories by the same author.”

Elena Krovvidi contributed to this report.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox