Russians share food in moveable feasts

"Rescuing" surplus food from retailers. Source: Alexandra Lyogkaya

Nearly every person in the Western world is guilty of throwing away food from time to time, while supermarkets and restaurants are well-known for their waste. But the sheer volume of edible produce that goes uneaten across the globe is staggering.

According to UN estimates, nearly one third of all food produced in the world (1.3 billion tons) ends up in the trash each year.

Those who share food are most dissatisfied with this state of things. Why throw away perfectly edible products, if they can be useful to someone else? The food sharing movement is trying to "rescue" food, collecting products that some people do not need and giving them to others for free. The movement originated in Germany, and has recently spread to Russia.

Food rescuers

"We are a strictly non-commercial project. Even the barter of food is prohibited," said Alexandra Lyogkaya, a 26-year-old St. Petersburg resident. In December 2015, she founded a community called "Food for Free" on the Russian social network VKontakte, pioneering food sharing in Russia.

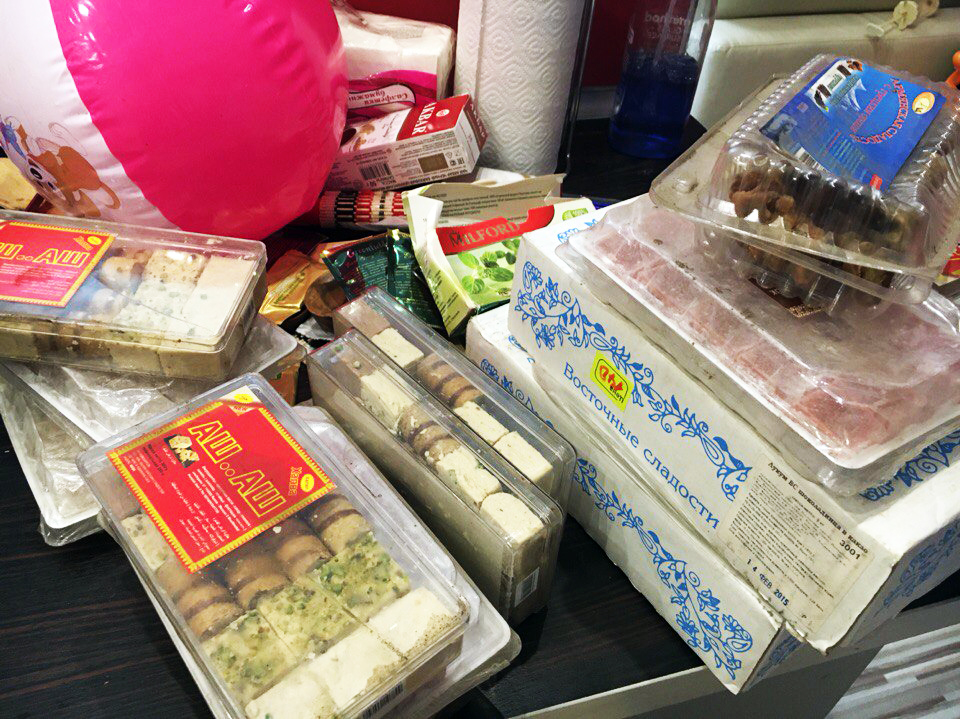

Food sharers' ‘trophies.’ Source: Alexandra Lyogkaya

Food sharers' ‘trophies.’ Source: Alexandra Lyogkaya

The project till now has more than 20,000 subscribers, while similar communities have been mushrooming across the country in places like Siberia, Tatarstan, and Karelia.

The food sharing system is very simple. If someone wants to give away a jar of salted cucumbers that they do not need, they place an ad with their address in the VKontakte community, saying, for example: "I don’t like so much salt in cucumbers, take it."

Whoever is the first to post an "I'll take it" comment gets the cucumbers. There are no social preferences, all that matters is speed. Previously, users wrote sentimental stories about their dozen hungry children, but organizers called for it not to be decided by people's literary talent and to give away food based on the objective criterion of speed.

However, this is only the tip of the iceberg. There is a more important task – hotels, restaurants, and factories throw away kilograms of quite edible products every day. But while ordinary people actively share their surplus food, Russian food sharers still have a problem establishing contact with major companies.

Bakeries and small shops in Moscow, St. Petersburg and Krasnodar (745 miles south of Moscow) are already involved in this process.

Food sharers' ‘trophies.’ Source: Alexandra Lyogkaya

Food sharers' ‘trophies.’ Source: Alexandra Lyogkaya

"In one Krasnodar shop, they were so excited about the idea that they wanted to send their surplus products to Moscow," said Lyogkaya.

Once, "food rescuers" got a whole batch of milk when a small shop had its electricity supply cut off for a few hours. It is forbidden by law to sell milk that is in a refrigerator without power, but they didn’t let it go to waste.

Who cares?

It is impossible to create a portrait of the average food sharer. The movement involves students, pensioners, businessmen and workers. Most of the activists aim at environmental protection and the rational use of resources. In some cities, leaders of the movement also promote veganism.

Food sharers in St. Petersburg are closely connected with other Russian vegetarian and ecological organizations: It is largely because of their efforts that food sharing has seen such a meteoric rise.

There is a social side of the issue, which comes to the fore in some places.

"Many of our participants are students, so they know what it means to barely make ends meet," said Nadezhda Medvedeva, the founder of a food-sharing community in Tomsk (1,740 miles east of Moscow).

In Voronezh (290 miles south of Moscow), surplus food is collected by volunteers with the Salvation Army.

Food sharing in Russia still has a long way to go.

"Many people are afraid of the opinions of others, who might assume that you take handouts," complained one activist from Almetyevsk (580 miles east of Moscow).

"Without serious promotion among online communities, people do virtually nothing. They do not even want to take food," said Yekaterina Travushkina, founder of the food sharing movement in Novosibirsk (1,740 miles east of Moscow). The initial inertia has, however, already been overcome, and at least a dozen ads are placed in the main food-sharing communities every day.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox