4 legendary athletes from the Tsarist era

Russian Tsar Nicolas II with the Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna and courtiers after tennis

MAMM/MDFMany people think that sports gained notoriety in Russia during the Soviet period, when they were a fundamental feature of state ideology. Athletic achievements helped in creating an image of a great state, and they were used to emphasize the superiority of the Communist State. Even before the Bolshevik Revolution, though, great sporting successes had been accomplished in Russia. Athletes from Tsarist Russia took part in the Olympics in 1900, 1908 and 1912, and one even became an Olympic champion.

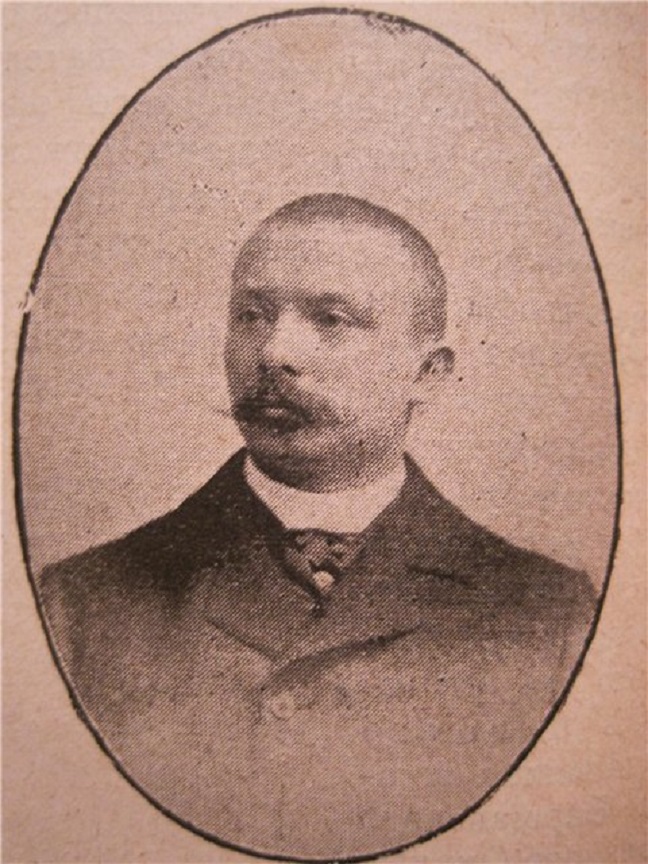

Pyotr Zakovorot: fencing

The 1900 Paris Olympic Games are now considered to have been a complete failure. The second time the modern international competition had been held, they coincided with the World Exhibition and received much less attention than the great scientific and technological achievements presented at the fair. Furthermore, sport at that time was rarely professional, and, of course, there was no commercial advertising to promote it.

It is not surprising that all five athletes from Tsarist Russia who participated in the games were military officers and that their athletic specialities came from their profession: three of them competed in fencing, and two participated in harness racing, riding on horseback while pulling a cart.

Pyotr Zakovorot finished seventh in fencing and came closest of the Russian athletes to becoming champion. After the games, he taught fencing in several military schools in St. Petersburg, and after the Bolshevik Revolution, he trained Red Army personnel for combat. Zakovorot taught several famous sportsmen, including Ivan Manaenko, the best Soviet fencer of the 1940s and ‘50s. Interestingly, Zakovorot himself won his last tournament in 1935, becoming champion of the Ukrainian SSR at the age of 64.

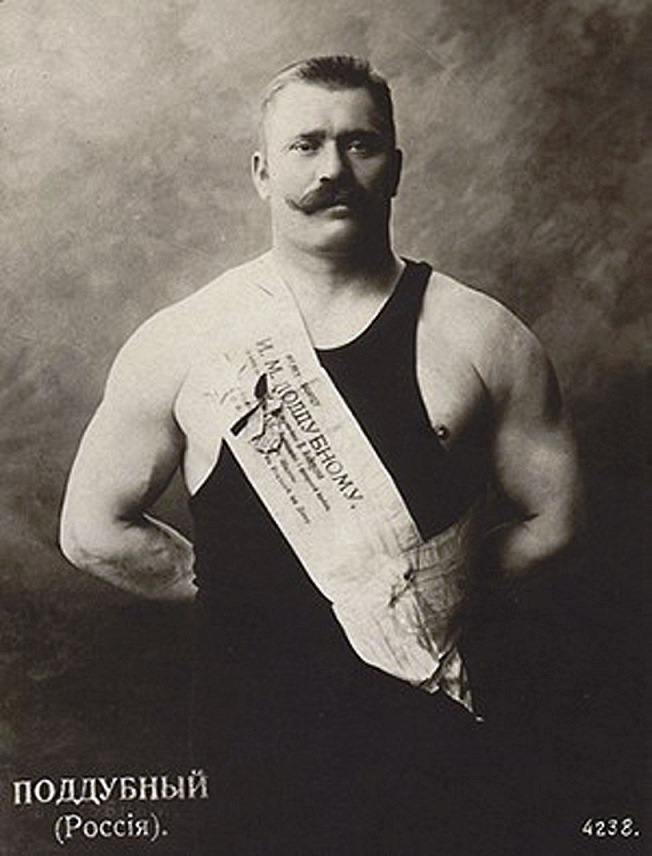

Ivan Poddubnyi: wrestling

Source: Archive photo

Source: Archive photo

The famous wrestler Ivan Poddubny was never a professional sportsman. Before he found fame, the strongman worked as a labourer, a longshoreman and a circus artist. In the arena, he showed off his skill at weightlifting, and in the circus, he began to master traditional Russian wrestling and later Greco-Roman wrestling.\

Poddubnyi gained notoriety as an athlete only at age 32, entering the world championship in classical wrestling in 1903. His first professional bout ended in defeat, when he lost to the Frenchman Raoul le Boucher, who slyly covered himself in olive oil, thus managing to delay the fight. In the end, le Boucher was declared the winner for his "beautiful and skillful evasion of powerful techniques." A year later, Poddubnyi managed to get his revenge on Boucher, and between 1905 and 1908 he held the world title in wrestling.

During his prime, Poddubnyi was the real headliner of any wrestling tournament. A true showman in the sport, he was the prototype for modern boxers and MMA fighters. After the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, he returned to the circus. Despite his abundant victories and state prizes, Poddubnyi spent his final years in poverty. In 1949, he died at the age of 79 in his hometown of Eisk (780 miles south of Moscow).

Nikolai Panin-Kolomenkin: figure skating

Source: Archive photo

Source: Archive photo

The first Russian Olympic champion, Nikolai Kolomenkin, was never paid a kopeck of his prize money for bringing victory to his homeland. Furthermore, he was threatened with exile to Siberia for his participation in the London Games in 1908.

The sportsman went to England illegally, under the pseudonym of Panin. It was surprising that he was able to do this, after already having been named Russia’s best figure skater five times in a row. Legend has it that his performance in ‘Men’s special figures’ scared off the famous Swede Ulrich Salchow, and that the seven-time world champion withdrew from the event after seeing the figures Panin was going to perform.

After the Games, Panin's deception was discovered when it was revealed that the talented figure skater was, in fact, Nikolai Kolomenkin, a financial inspector in the Tsarskoselsky region. According to the federal statutes of the time, state officials were not allowed to take place in athletic competitions. Panin had to stop competing; however, his passion for the sport did not diminish. In 1910, he released a textbook on figure skating and, in 1914, he was a judge at the world championships in Stockholm.

In the USSR, he concentrated on coaching, not only in figure skating but also in shooting. His shooting skills came in use during World War II, as well, when he worked as an instructor for partisan groups.

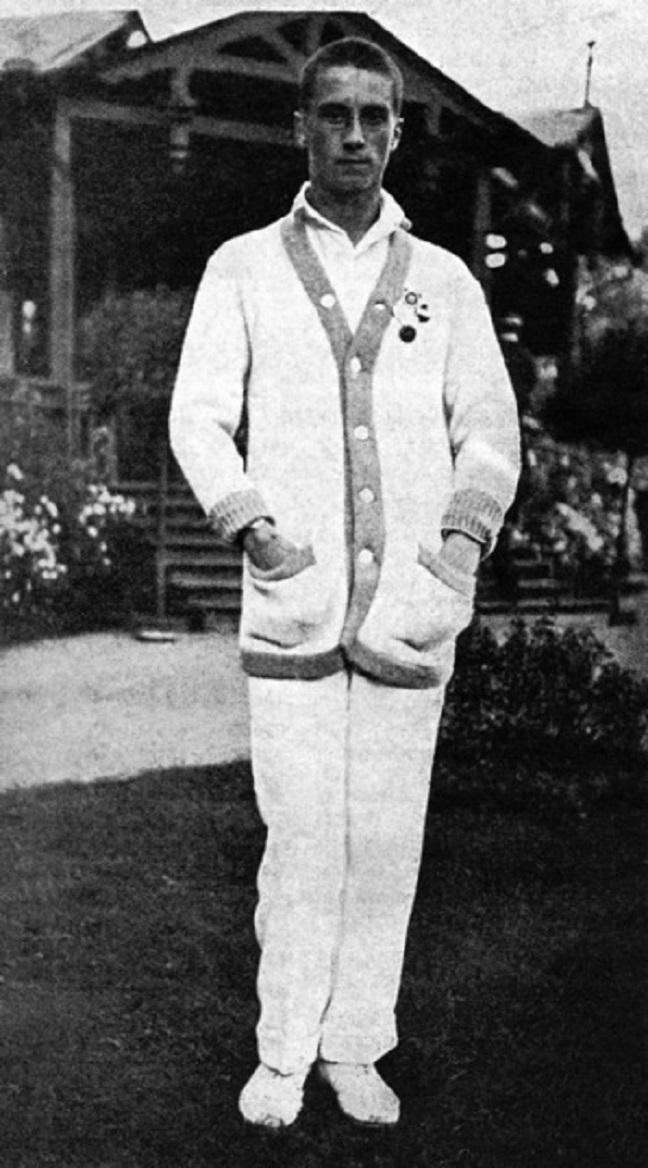

Mikhail Sumarokhov-Elstone: tennis

Tennis was one of the Russian aristocracy’s main pastimes in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The best Russian tennis player of the time was Count Mikhail Sumarokov-Elstone.

In 1910, the 16-year-old boy, much to everyone's surprise, won the Russian tennis championship. He retained the title until he went to war in 1914, even when well-known foreign masters competed in the Russian championships. For example, in 1913, Sumarokov-Elstone beat the Frenchman Maurice Germot, who won the silver medal in 1906; and he defeated the Englishman Charles Dixon, 1912 Olympic silver medalist.

In 1913, the young count had an even more precarious match. Tsar Nikolai II, a great fan of tennis, wished to play against the talented player. “Sumarokov, the left-hander, won all of his sets. After tea, the king asked for a rematch. Sumarokov hit the ball such that it hit the Tsar on the leg, who thereafter fell and had to lie in bed for three days. The poor champion was in despair, although the fault was not with him of course, not at all,” the head of the court chancellery, Aleksander Mosolov, wrote about the events at the Livadia Palace in Crimea. Nikolai II himself wrote a little more briefly in his diary that evening: “It was a good game of tennis with Sumarokov.”

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox