Mystical Sochi: Greek legends, Adyghe tales and treasures of the Olympics

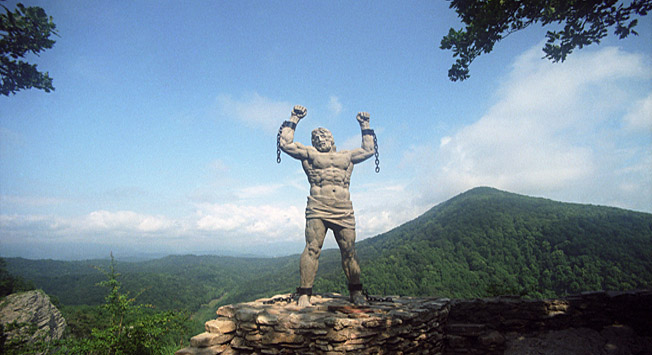

Prometheus myth

Photo credit: TASS/Victor Klyushkin

A beautiful and cruel legend is related to the Orliniye skaly (Eagle's Rock) on the outskirts of Sochi. It is believed that the Greek god Zeus nailed Prometheus to these very rocks to punish him for granting fire to humans. A local girl named Agura tried to ease the sufferings of the young god by secretly providing him with water. She did this until she herself was turned into a raging river at the foot of the rock. This is considered an example of how ancient Greek myths and Adyghe legends have sometimes merged into one folk tale. Today a symbol of this union here is a statue of Prometheus, whose image was cast into stone and placed on the top of Eagle's Rock. To this day mountain eagles make their nests here up.

The treasures of the Olympics

Photo credit: RIA Novosti/Igor Zarembo

In the mountains of Krasnaya Polyana near Sochi the builders of the Olympic sites found numerous valuable historical objects. An army of 100 archeologists arrived from Moscow and immediately began massive excavations. During the construction of hotels and sport facilities, at the depths of dozens of meters archeologists found the foundations of ancient temples and more than 4,000 artifacts: ceramics, cold steel arms, silver jewelry and coins. After the findings were studied and evaluated by experts they became exhibit items in the historical museums of Sochi and Krasnaya Polyana.

The stones of power

Photo credit: Lori/Legion-Media

The Volkonsky dolmen, the object that tops the chart of Sochi's anomalistic sights, is known for its powerful mystical energy: here time travels in the opposite direction, water changes its course, measuring instruments go off the rails and humans are relieved of anger and anxiety. The dolmen, which is located behind a forest of unusual trees, is made out of one piece of rock, unlike other dolmens that are often composed of multiple stone plates. Travelers come here to improve their health and recharge their bodies with the energy of this ancient monolith. The most ardent believers spend days and nights inside the dolmen clinging to the hope that this will cure them of serious diseases.

The ghost bride

Photo credit: Lori/Legion-Media

Every local resident has heard about the ghost bride who has lived on Akhun Mountain for 15 years; some have even seen her with their own eyes. The internet features several curious videos and photographs of a half-transparent silhouette of a young woman. Locals say that drivers who have stopped their vehicles here out of curiosity have gone missing with their cars. The ghost bride appeared on the mountain after a wedding procession car crash in 2001. The bridegroom survived but his young beloved bride died. Wedding celebrations on Akhun Mountain are an old tradition. The newlyweds go up to the top of the tower to find a place to take photographs with the Caucasian Ridge and the sea in the background. I wonder how many of these pictures have captured the image of the ghost?

The secrets of an old park

Photo credit: TASS/Igor Zotin

Dendrary Park in Sochi has been open for more than 100 years and during this time it has become overgrown not only with lianas and ivies, but also with secrets and mysteries. Local residents attribute magical qualities to the park’s sculptures. Dendrary hosts the Sochi equivalent of the Roman Bocca della verita, Mouth of Truth. The version here is a bas-relief called the Lion's Face. A spooky story is connected with this sculpture: once upon a time the lion closed his jaws when an unfaithful wife put her hand in his mouth. Since that time women who want to prove their faith to their husbands come to this mystical place to test the legend.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox