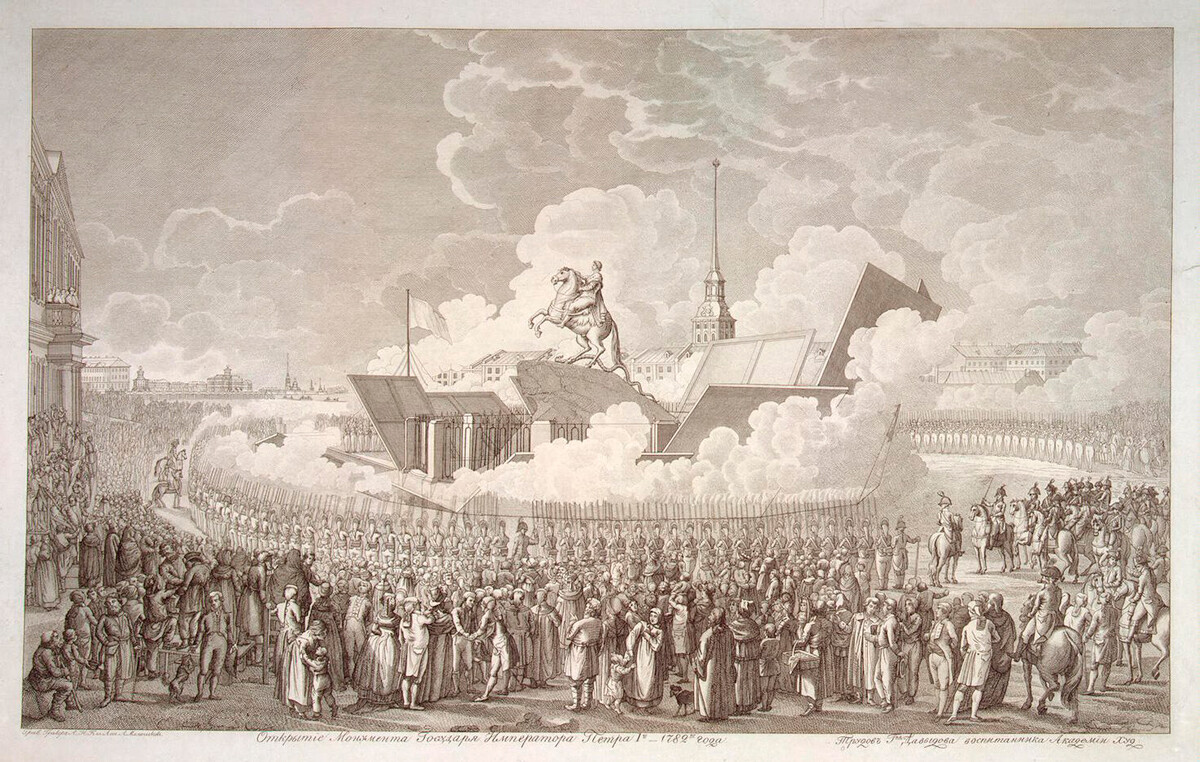

Opening of the Monument to Peter the Great. Engraving by A.K. Melnikov from the drawing by A.P. Davydov, 1782

Public domainIn August 1782, a monument to Peter the Great was unveiled on Senate Square in St. Petersburg. One side of the pedestal contains a caption in Russian, “ПЕТРУ перьвому ЕКАТЕРИНА вторая лѣта 1782” ([to] PETER the first [from] CATHERINE the second, year 1782); and the other side has the same phrase in Latin, "PETRO primo CATHARINA secunda MDCCLXXXII".

Catherine the Great came up with the idea of erecting a monument to the first Russian emperor. The German princess was the wife of Peter III, the grandson of Peter the Great. She seized power by overthrowing her husband to become empress of all Russia, and then she spent over 30 years on the throne expanding the empire, conquering new territories and founding new cities. In this sense, as a powerful builder of the modern Russian state, she considered herself the full-fledged successor to Peter the Great and his vision to make Russia powerful.

Vasily Surikov. View of the Monument to Peter the Great in Senate Square, St. Petersburg, 1870

Krasnoyarsk State Art MuseumThe famous French sculptor Etienne Falconet was commissioned to make the statue. He was recommended to Catherine by her friend, the philosopher Denis Diderot. In order to make a sketch of the equestrian statue, Falconet asked a Guards officer to mount the horse on its hind legs over the course of many hours each day. That’s how he made the drawings. At his disposal while working on the monument was the entire building of the temporary wooden palace of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna.

A laurel wreath on the head of the statue is the only thing that indicates his military triumphs as emperor

Legion MediaThe sculpture of Peter was expected to be different. In fact, many expected it to be a pompous monument with a complex composition and many allegorical figures. However, Falcone decided otherwise. "My monument will be simple," he said, limiting himself to the figure of Peter, dressed in simple clothes - a Roman toga and cloak (to suit the emperor's ascetic tastes). Instead of a saddle, there’s a bear-skin on the horse.

Falconet also rejected the idea of presenting Peter as a conqueror and warlord. "Much higher is the personality of the creator, the legislator, the benefactor of his country, and that is precisely what must be shown to the people," the sculptor said. According to his idea, Peter's arm stretches over the country he was building. Nevertheless, a laurel wreath on the head of the statue indicates his military triumphs as emperor.

Catherine the Great approved the design made by Falconet's apprentice, the young Marie-Anne Collot

Florstein (CC BY-SA 4.0)Falconet, however, didn’t create the Emperor's head for the composition. Catherine the Great, who played an active role in the preparations, rejected all three sketches that the Frenchman made. However, the sculptor's apprentice, the young Marie-Anne Collot, offered a design that the Empress approved. The posthumous mask of the emperor served as the model, and a plaster copy of the prototype head is now kept in the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

The serpent is another monument’s support

Legion MediaRussian sculptor Fyodor Gordeev completed another important detail: a serpent that the horse tramples with its hind hooves. This serpent symbolizes the hostile forces defeated by Peter (as well as the opponents of his reforms).

In addition to its symbolic and aesthetic function, the snake has a very important technical purpose. An equestrian statue of this size simply could not stand only on two hind legs, so the serpent is one of the monument’s secret supports.

Transporting of the Thunder Stone, 1770

Public domainA particularly difficult task was to find a huge stone to serve as the pedestal. The newspaper St. Petersburg Vedomosti published a call to action for people to search for a suitable stone. A local peasant found one on the outskirts of St. Petersburg.

The transport of this 2,000-ton monolith over a distance of 7.8 kilometers took half a year. Special piers and a ship were built to ferry it from one shore of the Gulf of Finland to another. A ship was then sunk so that the stone could be carried ashore.

In 1778, Falconet left Russia, taking all the sketches and project design papers with him

Rijksmuseum / (CC0 1.0)The plaster model was ready and presented to the public a year after Falconet began his work in 1769. However, the sculptor was unable to cast the monument. His assistant from France arrived in St. Petersburg, but also failed to complete the work. The first casting was made only in 1775, supervised by Vasily Yekimov (and not all pieces were successfully completed). Another three years later the work on the sculpture was completed. Architect Yuri Felten took part in the installation.

In 1778, Falconet left Russia due to a conflict with Catherine's personal secretary who supervised the project. The sculptor took all the designs and sketches, which also hindered the monument’s installation. It was only completed in 1782.

Russians call it “copper” horseman

Alexei Danichev/SputnikThe monument to Peter the Great was cast in bronze. His famous nickname ‘The Bronze Horseman’ owes to the work of Alexander Pushkin - it was the same name of his poem in 1833. The poem describes the devastating flood that inundated St. Petersburg in 1824, where, according to the story, the hero’s beloved died. Unable to bear his grief, Eugene goes mad. Passing by Peter’s monument, the “bronze idol on its horse”, Eugene blames the tsar for the flood and for having built the city at the mouth of a river. After uttering angry words at the Emperor, Eugene runs away, but ever then it seems to him that everywhere he goes “the Bronze Colossus on its steed charged at the gallop” is after him.

In fact, however, Pushkin used the Russian word “copper” in his text, not “bronze”. Probably he used this word for a proper rhyme, but ever since then Russians have called the bronze monument - ‘the copper horseman’.

"As long as I am in my place, my city has nothing to fear!"

Florstein (CC BY-SA 4.0)Many local myths and legends have arisen around the Bronze Horseman. One is probably served as the basis for Pushkin's work. During the war in 1812 between Russia and Napoleonic France, Russian troops were retreating and there was a threat that the French would occupy St. Petersburg. Emperor Alexander then ordered the evacuation of valuable works of art from the city, including the monument to Peter. But according to legend a certain Major Baturin told a friend of the tsar that he had the same obsessive dream. Allegedly, he saw Peter on horseback riding up to Alexander's palace and told him, "As long as I am in my place, my city has nothing to fear!" The tsar was told about the dream, and so he refused to take the monument away. The city, of course, was never taken by the French.

Lenfilm studio logo

LenfilmThe extremely emotional, dynamic image of both the emperor (and city founder) and the horse has inspired many artists. The city’s official film studio, Lenfilm, has long used the bronze horseman covered by two searchlights as its registered trademark.

The image of the horseman appears in paintings, on postcards and stamps, as well as on commemorative coins. The “Bronze Horseman” has become a cultural phenomenon in its own right - a popular opera was written based on Pushkin's poem. The statue also appears in other literary works, including Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Adolescent (a.k.a. A Raw Youth): “a bronze horseman on a panting, overdriven steed”.

The “Bronze Horseman” has become a cultural phenomenon in its own right

Alexander Galperin/SputnikIn addition, the statue also inspired the great jeweler Fabergé. The 1903 Peter the Great Easter Egg was dedicated to the 200th anniversary of St. Petersburg and was commissioned by Nicholas II as a gift for his wife, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. When the egg is opened, the sophisticated mechanism lifts up the miniature golden monument.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox