Cape Dezhnev is the easternmost mainland point of Russia.

Alexander KislovA high, cliffy shoreline, plunging steeply into the icy, raging sea and rattling wind, which almost blows you off your feet. This is Cape Dezhnev, the easternmost mainland point of Russia — and of entire Eurasia.

The very edge of the continent lies in the remote area of the Chukotka Peninsula (Russia’s Far East) at a cape as high as 740 meters. There, you can see a lighthouse monument to Russian Cossack Semyon Dezhnev, who was the first to reach that point. There is a plaque visible from the sea, with a commemorative inscription and a bronze obelisk to Dezhnev himself.

Prior to the mid-1950s, when the current lighthouse monument was erected, there was merely a wooden cross. You can walk round the obelisk, down to the deserted Eskimo settlement of Naukan. Up until the middle of the 20th century, it was the easternmost settlement of Eurasia, permanently inhabited by 400 people. Yet, in 1958, they were rehoused, as the village appeared to be too close to the U.S. border. What remains of their homes are just stone ruins and giant whale jaws, planted in the ground to serve as hangers for boats. These lands are considered sacred: there is no way you may curse there. Nor can you speak loudly, let alone desecrate the land by dumping rubbish.

In clear weather, you can see the Diomede Islands from there (the U.S.-Russian sea border lies right between them)… and even the shores of Alaska! In fact, there’s a total of 86 kilometers through the Bering Strait between Eurasia and the U.S.; and a mere four - between the Diomede Islands.

Cossack Semyon Dezhnev (ca. 1605-1673) is one of Russia’s legendary pioneers. Born in a village in Arkhangelsk Region (in the Russian North), he first served as a sailor on merchant ships and then as a Cossack in Siberia. In the late 1630s, he ended up in Yakutia, where he collected taxes from the locals. The job was life-threatening: he had to search for people in the dense taiga and tundra forests; and let’s be straight, not everyone was willing to pay taxes.

During a number of such ventures, Dezhnev and a group of Cossacks discovered one of the major rivers of the Russian Far East, the Kolyma, as well as founded a few settlements. Finally, in the summer of 1648, his expedition left the Kolyma and traveled farther eastwards by sea, reaching the edge of the continent, which Dezhnev dubbed Cape “Big Stone Nose” in his notes.

The explorer also spotted two islands inhabited by indigenous peoples (they are now known as the Diomede Islands). Then, the expedition sailed round the cape downstream, eventually founding a small fortress (ostrog) on the spot of Chukotka’s future capital Anadyr. Their ship was wrecked off the Kamchatka Peninsula, but, a few months later, the group managed to make it back to Yakutsk. Later on, Dezhnev explored the region of modern-day Chukotka, but never reached the cape: the undertaking was too dangerous. He died in Moscow, where he had come from Yakutsk to hand the collected money over to the state. By the end of his life, he already was the Yakutsk ataman (military commander of the local Cossack army), in charge of the entire ostrog.

In 1728, the expedition led by Vitus Bering, a Dane in service to Russia, reached the place. British explorer James Cook suggested that the strait be named in Bering’s honor, with the cape being called ‘Vostochny’ (‘Eastern’).

Not until the mid-18th century, when Semyon Dezhnev’s notes were found in the Yakutsk ostrog, did it come to light that his expedition had reached the point way earlier. In 1898, Cape Vostochny was renamed Cape Dezhnev, as suggested by the Russian Geographical Society.

Even nowadays, a trip to Cape Dezhnev is something truly extreme and it requires both physical and mental training. The edge of the continent is a concentration of strong, piercing winds, which one can hide from either behind a volcanic hill or behind the monument to the pioneer. The weather is constantly changing: one moment there’s sunshine and the next moment it gives way to gloom, rain or snow. There’s untamed nature all along the way and an almost zero chance of meeting a human. However, the place is visited by as many as several hundred tourists a year, accompanied by experienced local guides. So, better not travel here on your own.

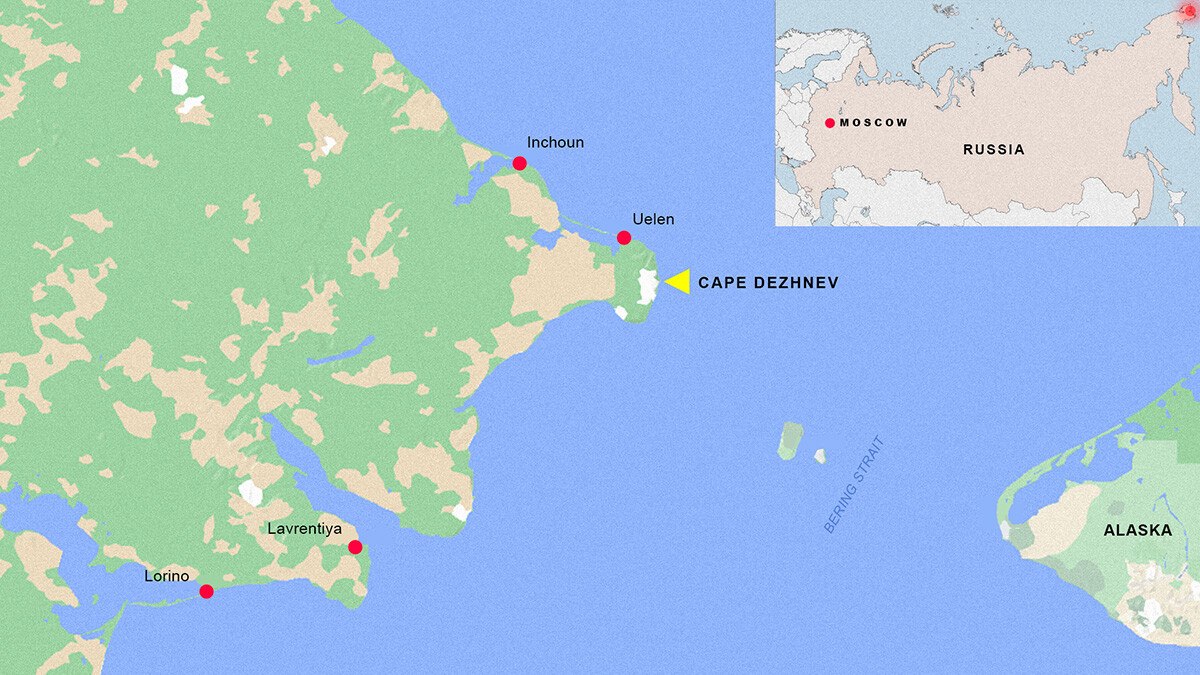

The first way to get here is to take a hiking trip. The closest inhabited settlement to the cape is the eastern village of Uelen, which is 10-15 kilometers away across the tundra. Yet, the most common route starts in the village of Lavrentiya, where the airport is. It is about 100 kilometers away from the cape. A hike is the cheapest and the most challenging option.

The second — and the most popular — way to reach the cape is going on a boat expedition from Lavrentiya. Tourists sail over the icy Bering Sea for several hours, before either spending a night in tents near the cape or making a return journey after a bit of rest.

It is also possible to reach the cape as part of a sea cruise. Yet, one will still have to take a short motor boat ride from the ship to make it to the final destination. It is the most expensive, but convenient option.

In extremely rare cases, one can fly to the cape from Lavrentiya in a helicopter. Due to strong side winds and the cliffy shores, only pilots with great expertise can land it there — and only in really good weather.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox