Giant house numbers are visible from afar.

Pavel KuzmichevAt first glance, Norilsk, situated in the north of Krasnoyarsk Territory (in Siberia), looks like a typical industrial city built according to Soviet architectural canons: official buildings in Stalinist Empire Style, dormitory suburbs with multi-colored ‘panelki’ (panel-built apartment blocks) and endless industrial plant chimneys stretching beyond the horizon.

A monument to metallurgists in the center of Norilsk.

Pavel KuzmichevBut just imagine: On this 69th parallel (300 km inside the Arctic Circle), the snow lies on the ground for about nine months of the year. In winter, temperatures can drop to minus 45°-50° Celsius (minus 49°-58°F), but the worst thing are the blizzards that can literally knock you off your feet.

Norilsk street views.

Pavel KuzmichevThe Taymyr Peninsula near which the city is located is also known as the “graveyard of cyclones” - all Atlantic cyclones end their life cycle there and that’s why it is always windy. In short, it’s no holiday resort! Local meteorologists even use the term “weather severity”, since the stronger the wind, the harder it is to endure the cold and damp.

Leninsky Avenue, the main street of Norilsk.

Pavel KuzmichevDespite this, over 175,000 people live in Norilsk. It is the second largest Arctic city in the world (the largest is Murmansk with a population of nearly 270,000, but it is situated a little further south). Nickel, copper, cobalt and palladium are mined and processed in the city (and for foreigners still need a special permission to visit it).

Norilsk Copper Plant. People at work!

Pavel KuzmichevThe plants operate round the clock and their employees must be able to get to work and home in good time.

From work or to work?

Pavel KuzmichevBut how can this be done when there is a terrible blizzard outside, not to mention the polar night?

Snow drifts in Norilsk, if they were not cleared in time, grew as high as a people's height.

Sergey Lobanov photo archiveThe problem of snow drifts has always been acute in Norilsk: They can reach 30 meters in height and huge resources have been used to clear them. The most important thing was to ensure the uninterrupted operation of the railway to Dudinka, which stretches across 100 km of deserted tundra and permafrost. The railway used to carry ore to the port on the River Yenisey, from where it was delivered to its destination by sea. And, in the opposite direction, food, household goods and parcels from the “mainland” arrived in Norilsk from Dudinka.

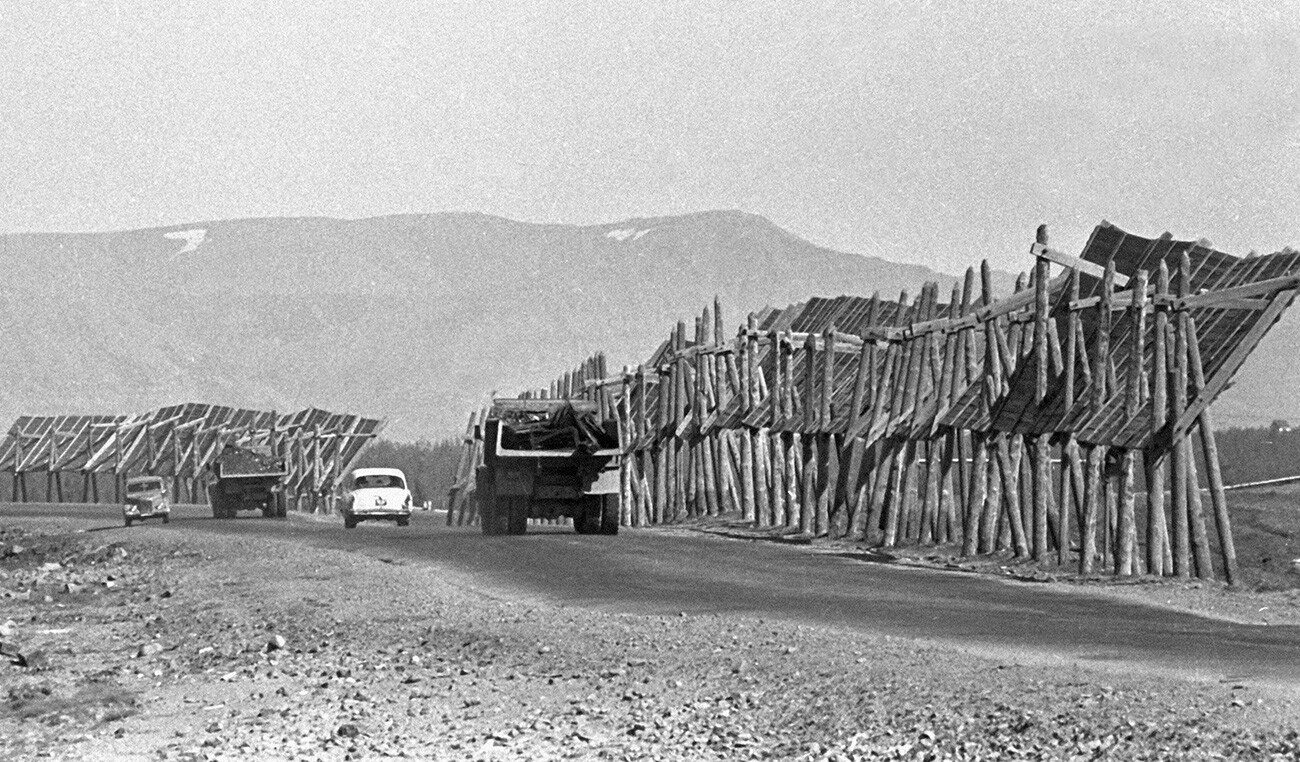

The road along which Potapov's shields are installed.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruToday, wooden snow barriers can be seen lining the roads. They were designed by Soviet railway engineer Mikhail Potapov. Norilsk was initially constructed using the forced labor of the inmates of the Norillag gulag camp (which was shut down in 1956). Potapov was a prisoner there in the late 1930s and early 1940s, having been sentenced to 10 years in the camps for his “association” with the purged Marshal Tukhachevsky (who had adopted a railway track weed burner invented by Potapov for the defense industry).

This is what the shields looked like in Soviet times.

Igor Vinogradov/SputnikIn Norilsk, the engineer was tasked with organizing an anti-snow system. Potapov walked the entire route of the railway on foot and came up with the following solution. The barriers made from his designs were to stand at a certain angle, ensuring that the wind emerges from underneath them with such force that it would sweep the snow off a road or railway track.

Potapov's shields nowadays on the road from the airport to Norilsk.

Pavel KuzmichevFor every section of the railway, the engineer calculated the right placing of the structures in relation to wind direction and speed. In 1944, Potapov was released early, but he continued to work in Norilsk until 1950 and eventually obtained an inventor’s certificate for his snow shield designs. His department was disbanded in 1950 and he left for a job in Kansk, another city in Krasnoyarsk Territory. But, he was re-arrested soon afterwards on the old charges and returned to Norilsk, where he died in 1954. His snow shields, however, stand to this day.

The Polar Empire.

Pavel KuzmichevNorilsk was granted city status in 1953. The plans for the city were (voluntarily) drawn up by Leningrad architect Vitold Nepokoychitsky, who came to the Polar Circle at the invitation of the head of the Norilsk (Nickel) Combine. Nepokoychitsky was an exponent of the Leningrad school of architecture, so the first buildings in the center of the city were put up in Neoclassical and Stalinist Empire styles.

Lenin's perspective.

Pavel KuzmichevThat is why the city’s central thoroughfare, Leninsky Prospekt, might appear to resemble St. Petersburg’s Nevsky Prospekt. It has the same monumental buildings opulently decorated with stucco moldings, only they stand on piles to prevent the heat from the houses from warming the permafrost.

This is what a courtyard looks like in the city center.

Pavel KuzmichevAnd, if you look from a distance at the streets of Norilsk, the houses appear to form a solid wall. This is also for protection against the wind.

Residential buildings in Norilsk.

Pavel KuzmichevSt. Petersburg’s lightwell-type courtyards were the inspiration for the design of the city.

One of the yards near the center of Norilsk.

Pavel KuzmichevThe masterplan for the construction of Norilsk was grandiose, but it was never fully implemented. The mid-1950s, following the death of Stalin, saw the start of a campaign against architectural excess and Norilsk ended up filled with standardized ‘panelki’. But, with distinctive features.

It can still fit a few people.

Pavel KuzmichevThe courtyards in the residential districts of Norilsk are constructed along “closed circuit” lines and the entrances are located on the inside. And there are openings with small sets of steps between the houses. Some of the openings seem very narrow - not enough for two people to pass.

And this is where only one should be left.

Pavel KuzmichevThis is done specially to allow residents not just to approach their apartment building entrance, but also to shelter from the wind and, additionally, to prevent the wind from blowing into the courtyard.

A snow storm in Norilsk.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/SputnikLocals say a “black blizzard” sometimes rages there: Accompanied by a very strong wind, it literally sweeps away everything in its path. The most devastating “black blizzard” was registered in early 1957. The snowstorm lasted for several days and ropes were even stretched from house to house to enable people to get around somehow.

"Black Blizzard" 1957.

Archive photoA large-scale refurbishment is currently taking place in the city: dozens of new houses are to be renovated and built, while courtyards are to be smartened up and utility networks modernized under a program set to be completed by 2035.

The numbers on the houses can be seen from afar.

Pavel KuzmichevOne of the striking and immediately noticeable features of Norilsk is the sight of enormous and colorful house numbers on buildings. They are visible from afar and in all weather conditions. This greatly simplifies the process of finding the right address in the middle of a blizzard, particularly for newcomers to the city. The numbers first appeared on panel-built apartment blocks in the 1980s.

House numbers can be seen both from the street and in yards.

Pavel KuzmichevThe numbers on old buildings, meanwhile, are of a standard design.

Soviet mosaics on houses.

Pavel KuzmichevAnother feature of Norilsk is that the buildings are painted in striking colors in an attempt to brighten the mood of local residents.

And modern mosaics.

Pavel KuzmichevA number of facades also display mosaics on the theme of the Far North.

A summer evening in Norilsk.

Pavel KuzmichevAnother interesting detail are the strings of festive lights that can be seen on many buildings. In summer, when there is daylight round the clock because of the polar day, the illuminations are naturally turned off. But, come the fall, all the streets are illuminated as if it were New Year’s Eve already.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox