Why India and Russia ignore each other

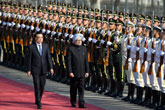

It is essential for young Indians and Russians to interact more. Source: RIA Novosti / Vladimir Fedorenko

On the night of October 22, the day Prime Minister Manmohan Singh left Moscow for Beijing, power from the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant seeped into the Tamil Nadu electricity grid. Certainly, it was a big moment for the country and the extensive coverage in the national newspapers reflected that moment.

Certainly, too, there was greater cheer about Kudankulam crossing the ‘lakshman rekha,’ a phrase in Indian mythology that refers to stepping out of your comfort zone, than there was about the 14th summit between Manmohan Singh and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Indians recognised that Russia had, once again, helped them to achieve a new high in India’s own development. It had been a Himalayan endeavour, having withstood the break-up of the Soviet Union – the first agreement had been signed between Mikhail Gorbachev and Rajiv Gandhi in 1989 – and the movement of the Indian state towards a much more capitalist orientation, and like the Himalayas the nuclear project had not allowed itself to be deflected by smaller events in both countries.

Over the last ten days, the 1000 MWe capacity reactor has been shut down twice for mandatory but routine tests, the second time after it began to generate 300 MW of electricity. Both Atomic Energy Commission chairman S K Sinha and Kudankulam site director R S Sundar are quietly ecstatic that India has been able to achieve such an incredible milestone.

There are other milestones in recent history, including building the engine for India’s first nuclear submarine, ‘Arihant’ (in Sanskrit the word means, the ‘Destroyer of Enemies’) in 2009 – for whose inauguration Russia’s former intelligence chief and at that time ambassador to India, Vyacheslav Trubnikov, was present at the Vishakapatnam dockyard. The BrahMos missile as well as the lease of a Russian nuclear submarine, since renamed the INS Chakra. (India asked for a second nuclear submarine during the Singh-Putin meeting.)

But take a look at all these milestones. They are all radically exceptional, in the sense that no other country in the world – including the US – will share military or defence or nuclear technology and expertise with India of this nature. Clearly, India is a huge defence market for Russia too. Why, then, do India and Russia continue to largely ignore each other?

I would like to argue that the biggest problem between our two countries today is that our peoples actually don’t know each other. In the good old days of ‘Hindi-Russi bhai-bhai’, when the world was much smaller and information much more controlled, a small elite group of journalists on both sides communicated the importance of the story to their audiences.

Which meant that when former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi visited Moscow in 1976, none other than the general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev, came to receive her at the airport and large parts of the city turned out to greet her as her motorcade whizzed past towards the Kremlin.

So what happened when Manmohan Singh went to Moscow in late October? The Russian media largely ignored the visit, while the Indian media was, honestly, far more interested in Singh’s forthcoming visit to Beijing.

In fact, Indian and Russian diplomats had chalked out quite an exhaustive agenda that could become the building blocks for a substantial relationship in the future. Both countries recognised that the private sector would have to take responsibility to add ballast to the foundations laid by the two governments in defence, science and technology, nuclear and aviation sectors.

So India offered to the Russians the opportunity to design and build a brand new township on the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor that Japan is helping India create. This could be on the lines of townships like Bhilai, the Soviets helped India build, or smarter, more intelligent cities that are on the cutting edge of technology. There was a real conversation on India signing a Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement with the Eurasian Economic Community so as to smoothen barriers for free trade, which could in turn link up with the proposed North-South corridor that has been a dream for more than a decade now.

There were other path breaking decisions that were taken in principle. The first is the setting up of a study group which will look into the possibility of linking Russian gas-fields to India by building a pipeline that will run parallel to the TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) pipeline, which is connecting the Indian market with Turkmenistan’s huge gas fields.

As an Indian diplomat said, “We asked ourselves how we could get around the burden of geography that the Himalayas provide and take a leaf out of the Russian pipelines that go east to China and west to Europe...Why couldn’t one pipeline come south?”

So why was there such dreary reporting from Moscow on the Manmohan Singh-Putin summit?

The truth is that in today’s brave new world, which is admittedly a much shinier place and where our attention is far more divided, the job to communicate the India-Russia story is a much more difficult one. And this becomes even more difficult when our peoples don’t meet – apart from Russians making parts of Goa their preferred habitat – because of the plethora of problems that dog the ordinary Indian visitor. Would President Putin help new-age Indians and Russians get to know each other better with more streamlined visa procedures?

The writer is a political and foreign affairs analyst based in New Delhi, India. Her Twitter handle is @jomalhotra

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox