TROIKA REPORT: Moscow seeks full integration into Asia, but what can it offer?

1. Engaging the West

Negotiations on Ukraine: a marriage of convenience amid new crisis

Clashes broke out between police and protesters outside the Ukrainian parliament in Kiev on Aug. 31, 2015 after a vote to provide greater powers to separatist regions in the east. Source: Reuters

A stormy session in Ukraine’s parliament this week while debating the proposed decentralization of governance in the eastern Donbass region, followed by a bloody riot in Kiev, signaled a new round of the political turmoil in Ukraine this week.

The unrest presents a serious risk of another change of government and the ousting of Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. This could bury the Minsk peace accord hammered out by Ukraine, Germany, France, and Russia in February.

The violence in Kiev has accentuated the crucial importance of international mediation and could give new impetus to Russia’s participation in talks on the resolution of the crisis. With Ukrainian radicals vehemently opposed to any form of autonomy for the rebel regions in the Donbass and the ruling coalition in danger of collapse, Poroshenko has little room for maneuver, and, willing or not, has to rely on the support of Berlin and Paris.

Last week the leaders of France and Germany took the initiative into their hands by conducting trilateral talks with Poroshenko with the apparent aim to accelerate the implementation of the Minsk agreements. Russian President Vladimir Putin was pointedly not invited to the talks.

In the aftermath of the meeting, called in the wake of a new upsurge in violence in eastern Ukraine, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande phoned Putin to tell him that the elections planned by the rebels would endanger the Minsk peace process. In return, Putin voiced his concern over what he alleged was a massive Ukrainian army build-up on the borders of the self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Lugansk.

Skeptics claim there is no chance of the Minsk accords being implemented by December. Is such pessimism justified? Prominent political analyst and public figure Sergei Stankevich, a senior expert with the Anatoly Sobchak Foundation, made this comment for Troika Report:

“The most important recent development was that the essence of the conflict has changed. Previously, it was a conflict with separatists. Now it is a conflict with “autonomists” since the leaders of Donetsk and Lugansk have declared as their goal to become autonomous republics or an autonomous region within Ukraine.

“This means that a critically important political compromise is possible. It means no secession, no separatism. The key topic of negotiations will be the volume of autonomous rights. Russia should now concentrate the talks on this issue: the amount of autonomous rights.”

“The European powers, Germany and France, should approach Poroshenko and promote this idea of an autonomous status of Donbass inside Ukraine. President Poroshenko cannot insist on this solution without serious external support because of very serious internal opposition. Radical nationalist forces oppose any special status for the self-proclaimed republics of the Donbass.”

Despite growing criticism of the effectiveness of the Minsk peace process, which is being supervised by four negotiating parties, this format of conflict resolution has not yet passed its expiry date. Why are the leaders of Germany, France and Russia reluctant to abandon this model? Sergei Markedonov, associate professor at the Russian State University for the Humanities, offered his explanation to Troika Report:

“First of all, this situation is paradoxical. Until now, the Minsk agreement is the only document which incorporates different views. Russia and the Western states refer to this agreement as the basis of conflict resolution. But the warring parties are pursuing divergent goals that are incompatible; what’s more, they want to maximize their gains.

“However, neither of them have the appropriate resources to achieve these goals. This is another reason why Russia and the two Western powers are pinning their hopes on the Minsk accords. There is a faint chance that a compromise could be reached but the warring parties might still disrupt the peace process in pursuit of their interests.”

— We are witnessing a relatively sustained ceasefire, or at least the absence of large-scale armed clashes in the Donbass. Can this be assessed as a minor achievement of the peace talks?

“Basically, I agree. Neither of the conflict parties has the resources to achieve an undisputed victory. It compels them to seek a settlement through negotiations.”

“But it is necessary to discuss in parallel with conflict resolution in Donbass the basic principles of European security. I suppose that the engagement of Russia would be a good chance to ensure a stable and predictable security situation (in Europe).

“The legacy of the Cold War calling for ‘Russia — out!’ is not effective, and the crisis in Ukraine has proved it… Russia does not believe in European security based solely on NATO and NATO enlargement towards the East. Russia wants to be part of the security arrangements in Europe. It we want a fundamental settlement over the Donbass, we should focus on European security in general.”

— Do you suggest that Russia and other European nations should discuss the future security architecture on the continent?

“Yes, European crises — the conflict in Donbass and the conflict over the status of Crimea — were the consequences of a vacuum in security arrangements. Europe was perceived as a stable and predictable region but this was not true. The war in the Balkans demonstrated this. Just like the enlargement of NATO, the war in Georgia in 2008, and the protracted conflicts in the Caucasus and Moldova. This time it is the crisis in Ukraine which showed the vulnerability of Europe.

“In my mind, it is mandatory to resolve the conflict in Ukraine within a broader context. Or else we will have a repetition of such crises… It would be sensible to realize two goals: tactical — the resolution of the conflict in Donbass, and strategic — ensure European security in the long-term perspective.”

Troika Report shares the view that Moscow, Berlin and Paris seem to be putting aside their differences, having consented to a “marriage of convenience,” and are continuing to make concerted efforts to prevent a return to open hostilities in the Donbass, at least, and, hopefully, facilitate the gradual return of Ukraine to normality. As diplomats say, it gives ground for “cautious optimism.”

2. Globally speaking

WWII: What does failure of Allies to attend Beijing ceremony mean?

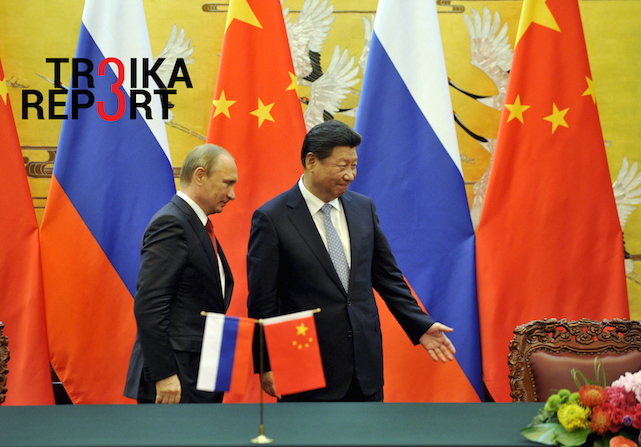

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) gestures to Russian President Vladimir Putin after their signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, Sept. 3, 2015. Source: Reuters

China’s grand celebration of the 70th anniversary of the final victory in World War II could have become a moment of truth and unity for world powers, but it did not.

At the biggest military parade in the history of China on Sept. 3 the seats reserved for Western leaders were empty, just like in May in Moscow. Among the 30 dignitaries, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, there was not a single Western leader in attendance representing the Allies.

Why? Could this be a sign that divergence of interests and goals among the major world powers is contributing to a growing instability in regional and global affairs? The time-dishonored historical rivalries have surged forth once again, thus threatening the gradual progress of the nations of northeast Asia toward more civilized societies and orderly inter-state relations.

The tense territorial disputes around the South China Sea, plans to amend the peace-focused constitution of Japan, China’s challenge to the ownership of the Tokyo-controlled Senkaku Islands, the build-up of the U.S. military presence in the region – all of these adverse developments give grounds for anxiety. Taken in historical context, it runs counter to the spirit of cooperation and search for compromises that triumphed for a short period of time in the aftermath of WWII.

Could the lessons of WWII be overlooked and willingly neglected without retribution from history, which is known to be such a rigid schoolmaster?

For Russia and China, the casualties of WWII remain an irretrievable demographic damage to be felt through many generations yet to come. Just for the record: while United Kingdom and United States lost fewer than one million (450,900 + 418,500) during the conflict, the death toll suffered by the Soviet Union and China is appalling in its scale: 25-28 million and almost 35 million, respectively. The price of freedom for the USSR and China was far too great to forget.

Does the legacy of WWII have the same impact on other major players in world politics? Was absence of Western leaders in Beijing a sign that the founding fathers of the post-war world order stand more disunited than ever? Yury Tavrovsky, professor of the Moscow-based Friendship University and a well-known Russian expert on China, made this comment for Troika Report:

“I think it’s a great mistake of the West and, in particular of the United States, to stage this boycott of the celebrations in China. It is the first time that the Chinese are celebrating their victory. It’s a turning point in the mood in society. The Chinese for 70 years remembered the war as a victim nation. They would remember the 300,000 people killed in Nanjing, the 35 million who died during the war.

“But a couple years ago the Chinese started to talk about themselves as a victor nation. They did not capitulate as the French did. For 14 years they were fighting off the Japanese troops. They won the war. The absence in Beijing of the leaders of the Allied nations is a great insult for the Chinese, and a big mistake.”

The symbolism of Russian President Vladimir Putin standing side by side with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping on Tiananmen Square will not be lost on the Western powers which have chosen the policy of “containment” of both nations, emphasized Tavrovsky. This solemn public appearance by the two leaders will underline the present strategic partnership, without turning it into a formal alliance, and bring the two nations even closer.

Yet, neither the personal chemistry of the two leaders, nor the enhanced cooperation and the upward trend in bilateral relations are projected on creating an environment of trust and understanding across northeast Asia that would pave the way to setting up something of a regional security mechanism.

Today, the Pacific Rim is not only the driver of global growth but also the scene of political discord and an arms race of unprecedented proportions. The multiple controversies over islands in the South China Sea have a global dimension since about a third of global crude oil and half of global liquid natural gas trade passes through these waters.

While more assertive Beijing pressures Tokyo over the Senkaku Islands (claimed by China), conservatives within the political class in Japan insist on revising the constitution to enable the armed forces to conduct “overseas” operations. However, in an unprecedented display of public protest, tens of thousands of ordinary folk in Japan have been demonstrating in the streets under slogans such as “War is over!” Opinion polls show that 70 percent of Japanese citizens are against a proactive military doctrine.

The escalation of the build-up of armed forces in Asia is worrisome and detrimental to efforts to set up an effective system of checks and balances in the region, which is prone to heightened tensions and, lately, has been balancing, in the case of the two Koreas, on the brink of an open military conflict. Hopefully, this worrying disregard of the lessons of the past, resembling a kind of collective amnesia, will not produce a sequel to WWII.

3. Going Eastward

Moscow seeks full integration into Asia, but what can it offer?

Members of the Eastern Economic Forum, which is taking place on Russky Island in Vladivostok. Source: Ria Novosti/Alexander Kryazhev

Three months after the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum saw Russia attempting to build bridges with European partners despite Western sanctions, the Eastern Economic Forum is being staged in the city port of Vladivostok. Aimed at opening windows of opportunities, the forum, in a wider context, is meant to flesh out and inject life into Russia’s widely proclaimed but not yet substantiated policy of its “pivot to Asia.”

The Vladivostok forum is being positioned as a twin to the St. Petersburg event. Is this a well-grounded comparison? What are the stakes for Moscow in the context of its “pivot to Asia”? Dmitry Mosyakov, an expert in regional affairs and head of South East Asia section of the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences, made the following comment for Troika Report:

“The comparison is justified, although the forum in St. Petersburg is already a well-established and widely acclaimed platform while the Vladivostok gathering has still all the characteristics of a start-up. Nevertheless, the latter is gaining momentum and credibility. Above all, it has the potential to turn into an effective mechanism for bringing together partners from East Asia and Southeast Asia.

“The initiative of putting together the Vladivostok platform of business dialogue has the advantage over previous enterprises due to a key element: For once, discussions and negotiations on the sidelines of the forum directly involve local, small and medium size businesses, meaning those registered and operating in the Russian Far East. It should be noted that the main drivers of growth in Northeast and Southeast Asia are clusters of small and medium-sized enterprises. Finally, Russia and its business are entering well-chosen and lucrative niche markets.”

Mosyakov placed high emphasis on the still hidden appeal of the so-called Advanced Development Territories in the Russian Far East. These territories are expected to play up to the expectations of low-risk investors keen to capitalize on the preferential treatment guaranteed by the Russian government. This will hopefully amount to a traditional set of attractive terms and conditions for doing business under a foreign jurisdiction, including tax holidays, moderate basic production costs, facilitated repatriation of revenues and profits, etc.

Nevertheless, the expert community in Moscow has conflicting views on the apparent opportunities opening up in the Far East. Since the early 1990s, Russia has been attempting to attract investors and partners from Asia’s economic powerhouses, but to little avail. Will the Vladivostok forum deliver anything more than upbeat declarations and vague promises? Andrei Fedorov, former First Deputy Foreign Minister of Russia, voiced careful skepticism in an interview with Troika Report:

“Everything depends on what Russia can offer to potential investors. I was in Japan not long ago and talked to businesspeople who complained that there are still too many legislative problems.”

“I am rather skeptical of the concept of the Advanced Development Territories, which is still merely a project not backed by a legal framework. It is an attempt to attract investors but the concept is still underdeveloped.”

True enough, the huge challenge is to complement the current long-term deals for the supply of primary resources like oil, gas, metals, coal, etc. to customers in Asia with delivery of goods with high added value, joint R&D and production, and also not commodity-based but services-focused trade.

The prospects of a soft and swift integration into Asian markets are being dimmed by the current turbulence affecting the Russian economy, especially the volatility of the ruble’s value against other currencies. This is epitomized by the dramatic downturn in economic interaction with China. Trade turnover crashed through the floor in the first half of 2015 with a 30 percent drop while Chinese exports nosedived by 36 percent. Tellingly, Russia is no longer one of China’s top 10 trade partners.

Statistics for 2014 provide a basis for moderately optimistic forecasts – industrial production in the region surged by 5.3 percent and agriculture production by 18.7 percent, both the highest growth rate in the Russian Federation. However, much has changed since then, and for the Russian Far East, which has been relatively disregarded for too long, a lengthy “catching up” period is inevitable.

The opinion of the writers may not necessarily reflect the position of RIR or its staff.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox