A spellbound traveler from Moscow to Petushki

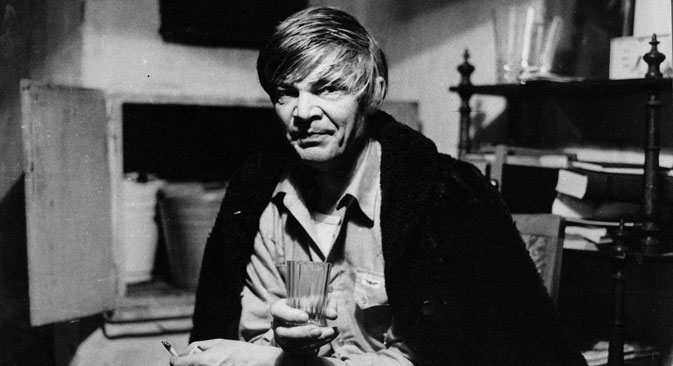

The protagonist of 'Moscow-Petushki' is Venichka. The most remarkable thing about him is his human soul, with its suffering, its glory and its failings. Source: Photoxpress

The mystery of Erofeev is a riddle without an answer. The storyline seems simple: Back in 1969, a drunken man boards a commuter train on his way to his loved one. He has a bit more to drink while on the train; he raves, he jokes, he talks to fellow passengers. And then he is stabbed. That, essentially, is the whole story. The mass-market paperback is only 187 pages long. These 187 pages, however, have won Erofeev passage to the pantheon of world literature.

Erofeev lived for another 30 years after finishing his masterpiece, but he wrote very little during all those decades. “Moscow-Petushki” was enough to win him a global recognition. The interpretations of the book, however, have always varied. To a man in the street, it is little more than foul-mouthed ravings of an alcoholic. To outcasts and nonconformists, it is an ode to their creed. To critics, it is the first example of Russian postmodernism. To people in the middle of a spiritual journey, it is an important religious text. Some even saw “Moscow-Petushki” as a protest against the Soviet system. To them, the moral of the story was that it is better to end up drunk in a ditch than to lead a false Soviet lifestyle, imbued with the ideology of slavery and lacking any liberty or freedom.

As is so often the case with truly great books, all of these opinions have some degree of truth in them. It is certainly true that there is a lot of drinking and drunkenness in books by Erofeev. In fact, alcohol drips from almost every single page. The most famous quote from Erofeev is, “And he immediately had a drink." Erofeev was undoubtedly an outcast and an escapist. A man like him will always be an outcast in any society, be it communist or capitalist.

There is also a lot of God-searching in his books, as well. Venichka keeps talking to angels and thinks of Petushki—a small speck of a town in the middle of nowhere, almost a utopian City of God. “Moscow-Petushki” is just as full of things divine as it is of strong spirits.

There is also plenty of postmodernism in the book. Erofeev’s lines sparkle, intertwine and tumble in a heap. He keeps mixing up the classics of Marxism with the classics of Russian and world literature. His philosophical maxims sit comfortably on the same page with Soviet slogans and platitudes.

The protagonist of the book, Venichka, is very tender and tragic. He is certainly not a fighter—not even a little bit. He is not an aggressive nonconformist; he is not an anti-Soviet dissident.

The most remarkable thing about him is his human soul, with its suffering, its glory and its failings. His soul is above any ideas or social constructs. And that is exactly why his ramblings sometimes take a dive into the pit of drunken delirium and sometimes soar sky-high like a prayer.

There is a lot that is quintessentially Russian about this book, but it turns out that there are many people who feel a certain affinity to Venichka’s soul all over the world. Below is a selection of comments by fans of Erofeev from all over the world. Each one of them offers a unique take on the famous Russian author.

David Macfadyen, Professor at UCLA in California, U.S.A.:

The basic opposition here is between goal-driven, social enterprise and the ability of alcohol to both allow and increase "wayward" thoughts. It lets the mind wander; society often does not. The story, despite its roots in Soviet experience, is fundamentally understandable anywhere. Escapism is not an exclusively Russian desire. Even this week, the BBC announced that Australia's Northern Territory has some of the toughest anti-alcohol measures in the world. That means the people living there are trying extremely hard to escape the pressures of "progressive" Australian society.

Wherever and whenever things are bad, similar characters will emerge as champions of escape—at least internally. "Moskva-Petushki" is a very specific literary response to a problem, but the underlying issues are universal.

Yolanda Delgado, Journalist and Slavic scholar from Spain:

“Why We Like Moscow-Petushki”

It must be because there is a Spanish saying that says drunkards and children only speak truths; they are a shock to anesthetized consciences.

It must be because Venichka belongs to crazy Quijote’s tribe. He pursues an unrequited love and, in his episodes of hallucination, regrets beings so lucid.

It must be because this drunkard belongs to the gallery of famous drunkards in universal literature.

It must be because Venichka, the writer’s alter ego, is a worker who looks at himself, his neighbors and the world with rage.

It must be because his disturbed intelligence condemns the pathologies of a society so ill that it makes the reader laugh, such that it eventually twists one’s mouth, because the reality he recounts is not funny.

It must be because Venichka gets on a train to go on a trip, and on that odyssey he never reaches his destination.

It must be because Petushki is the Promised Land for idealists.

It must be because it is the genius of a writer who dared to say aloud that he did not agree.

It must be because the book superseded the yoke of silence.

It must be because “Our tomorrow will be brighter than our yesterday and our today.”

Go! Go to Petushki!

Paolo Ferrando, Business intelligence analyst based in London:

I studied Russian at university, and Erofeev stands out in my memory as one of the most enjoyable readings from my final year syllabus. Certainly, those not familiar with the great authors of Russian literature might miss out on the incredibly rich subtext of the novel and on the grand cross-referentiality of Venichka’s story, which goes from mocking to moving without ever feeling superfluous or, worse, affected.

But most of Erofeev’s symbolism is great because it is universal, and no forceful attempt at pinning it down into one historical or literary context can add much to its interpretation. There is nothing in the sheer power of his narrative, in a story that is as realistic as it is magical, that a Western reader can fail to appreciate.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox